Publikationsserver des Leibniz-Zentrums für

Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam

e.V.

Archiv-Version

Youth Organizations

Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 16.05.2019 https://docupedia.de/honeck_youth_organizations_v1_en_2019

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-1353

Introduction

When Richard Etheridge, a seventeen-year-old Boy Scout from Birmingham, England, packed his backpack in the summer of 1951 and headed for Central Europe, his fellow Scouts never would have suspected that he wasn’t planning to attend the World Scout Jamboree in the Austrian town of Bad Ischl. Etheridge broke away from his troop even before he left England, venturing his way by ship from Dunkirk to Gdańsk and from there to his actual destination, East Berlin, where the World Festival of Youth and Students was taking place at the very same time. Upon his return from the German Democratic Republic he made no secret of his socialist sympathies. The story was picked up by the English press, which reported on the existence of these other “Red Scouts” and their fraternizing with young people on the other side of the Iron Curtain, with the result that a purported boyish prank turned into a formidable affair of state. The British Scouting Federation cracked down on internal deviants, parents bemoaned the manipulability of their children, and Labour Party deputies protested that the poison of McCarthyism had infiltrated one of the country’s oldest and most respected youth organizations.[1]

This episode from the early days of the Cold War is revealing in two ways. It illustrates the enormous significance of ideas and practices of adolescent communitization in societies highly mobilized around ideology during the twentieth century – a century that many consider the “century of youth” due to the increasing importance attached to adolescence.[2] Second, the case of Etheridge points to the historic role of youth organizations in the attempts of state and non-state elites to steer and contain the participatory demands of young people. The global expansion of this pedagogical innovation in only a matter of decades is indeed impressive. The camps, festivals, exercises, flag worship and rituals of initiation used to integrate children and young people, male and female, in existing systems of rule fascinated functional elites in ideological dictatorships, liberal democracies, and anticolonial movements alike.

The public and historiographical discussion of organized youth, a phenomenon which reached its pinnacle in Hobsbawm’s “Age of Extremes,”[3] has long been dominated by the image of uniformed young people marching in lock-step and singing in unison. Admittedly, with the almost one-sided focus on totalitarian mass organizations like the Hitler Youth or the Soviet Komsomol we run the risk of losing sight of the plurality, mobility and especially the flexibility of this pedagogical innovation. While the state and its supporting parties are prototypical sponsors of youth organizations, religious communities, trade unions, entrepreneurs and clubs likewise use youth organizations as urgently needed recruiting grounds, not least because self-confident youth are likely to demand more participation in the shaping of social and political systems.

Hence historians have meanwhile abandoned the older narrative of youth organizations as uniform indoctrination machines and begun to rethink these complex spaces of intergenerational socialization, located as they are on the interface between state and civil society, politics and recreation. They have studied the contribution made by organized youth movements to the construction of modern gender roles, as well as ascribing a pioneering role to organizations like the Boy Scouts in the formation of transnational and global networks. Alongside the rise of gender history and global history, crucial impulses have come from advocates of an actor-centered history of childhood, which has pleaded for the recognition of children and young people as (semi)autonomous historical agents who repeatedly elude the claims to authority exercised by their adult leaders.

The historiographical investigation of youth organizations is currently undergoing a veritable renaissance. The following contribution would like to use this as an opportunity to briefly outline the field’s development and explore its potential for future research. Such a large and multifaceted field makes setting priorities inevitable. The focus of my contribution is the relationship in the twentieth century between the Anglo-American-influenced Scouting movement and the state-youth movements of fascist and communist provenience – a specific angle primarily indebted to my own research interests in the history of youth and childhood in the transatlantic region. I will address other organizational forms in passing, including the party-affiliated youth groups of the Federal Republic of Germany. I will also discuss some path-breaking deliberations from the historical study of totalitarianism as well as important work on civic education and the extracurricular socialization of young people. Finally I will consider some approaches from gender and global history which have set new accents in the field since the turn of the century. But first we will need to define more precisely the key concepts of “youth” and “youth organizations” with recourse to the relevant literature.

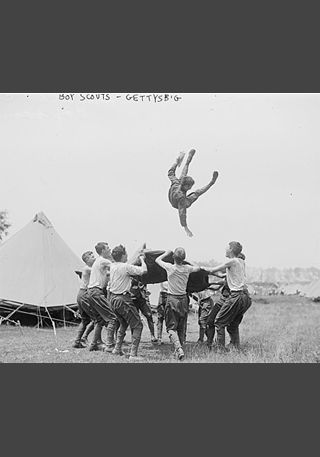

![Boy Scouts, Gettysburg, July 1913. Photographer: unknown. Published in: Bain News Service Photograph collection. Source: [http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.13849/ The Library of Congress] / [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Boy_Scouts_-_Gettysburg_LOC_3931075949.jpg Wikimedia Commons] public domain](sites/default/files/import_images/3559.jpg)

Concepts, contours, controversies

That youth organizations needed not only youths but also a serviceable concept of youth may seem like a truism. Yet historians unavoidably encounter a wealth of historical-cultural semantics that seem to render meaningless any attempt to establish a stable definition without regard to temporal context. Historian Detlev Peukert put it in a nutshell when he concluded that youth as a collective term was “remarkably non-uniform.”[4] It is therefore necessary to illuminate specific historical contexts where youths have played an active role. In the maze of interpretations on offer intended to provide some orientation in these specialist studies, the analyses which stand out most nowadays given the variety of historical experiences made by young people are the ones that avoid universalizing labels. This awareness of plurality is flanked by social-constructivist studies conducted on the topics of childhood, youth and old age. Purely quantitative approaches have been replaced by the investigation of the social relationships, legal regulations and cultural practices that socially generate the various life phases and age thresholds in the first place and allow them to change historically over time.[5] The way a society talks about youth as well as the actual opportunities open to young people are not free-floating analytical categories but are embedded in situational social realities differentiated according to structural principles such as gender, class affiliation, race and religion. Ivan Jobs and David Pomfret argue along these lines, their dual perspective of youth as a “cultural concept” and “social body” in need of historicization forming a productive starting point for the study of youth organizations.[6]

The discursive struggle to define youth, of course, was already a specifically historical problem, one that repeatedly crops up in sources, during the early phase of organized youth movements. An important figure of thought, which a heterogeneous coalition of youth leaders – educators, social reformers, nature lovers, officers and statesmen – referenced in Europe and North America, was the concept of adolescence popularized by American developmental psychologist Granville Stanley Hall (1846-1924).[7] The ideas of Hall and other educational experts from the turn of the century were very influential, establishing with the concept of adolescence a scientific theory of youth as an age of extreme experience and behavior distinct from childhood and adulthood. This relativized, though did not completely supplant, the cult of youth of post-Enlightenment nationalist movements, in which youth served as a romanticized metaphor of awakening, denoting less a specific age group than a critical attitude towards the traditional, often estate-based order of the older generation.[8]

Hall’s idea, inspired by evolutionary biology, that children should be able to act out their “primitive instincts” in the context of guided play offered a scientific legitimation for a range of pedagogical experiments such as the Woodcraft Indians in the United States and the Boys’ Brigades of Scotland, in which adults, together with children – often through bonding with nature, recreational activities or military-like drills – explored new and generation-spanning forms of togetherness.[9] These early experiments ultimately resulted in the Scouting movement, founded in England in 1908 by Robert Baden-Powell (1857-1941) and in many respects the prototype of modern youth organizations, particularly in light of their rapid dissemination in the Anglo-American world and their numerous international emulators.[10]

Inherent to the bivouacs and marches of the Scouts were structures that became characteristic of modern youth organizations in various geographical regions and political regimes. One standard feature were the quasi military uniforms of their members which not only suggested their affiliation to the state or state-related institutions but also symbolized the rootedness of the individual in a grand utopian collective, generally framed in national or imperial terms. No less important was the aspect of intergenerationality, turning youth organizations into a specific locus of mediation between the interests of young and old. Youth sociologist Jay Mechling speaks in this context of a “syncretic border culture,” which he describes as resulting from the complex interaction between “adult intentions and the youth’s desire to exercise as much autonomy as possible,” even if this interaction takes place within hierarchical formations [11]

Researchers who distinguish terminologically between the ideal types of “youth organization” and “youth movement” view intergenerationality in the latter case as an incidental factor and underscore the tendency of youth movements to (comparatively egalitarian) self-leadership. The Wandervogel movement, founded in Berlin-Steglitz in 1896, is often cited as a textbook example, a bündisch-nationalist coalition of bourgeois students and pupils critical of the materialism of modern civilization and hence seeking a more authentic lifestyle in the great outdoors.[12] Such rigid distinctions are rarely useful empirically speaking, as the self-positioning of those involved can turn out to be considerably more ambivalent. Baden-Powell had always despised the term organization, which he found too bureaucratic to genuinely reflect the campfire romanticism and playful fraternization of boys and men found in his Boy Scouts. The Hitler Youth, too, vacillated between being a movement and an organization; though adopting the “youth leads youth” motto of the older German youth movement, it unabashedly strove to absorb its members into the Nazi system of rule.[13] There is now a general consensus that the histories of youth movements and youth organizations constitute important segments of social and cultural history. It was Walter Laqueur who discovered microcosms of greater social transformation processes in youth organizations, noting in 1962 that the history of the German youth movement “is important for an understanding of Germany in the twentieth century.”[14]

Historians the likes of Tamara Myers, Sian Edwards and Olga Kucherenko have meanwhile come to see Mechling’s interaction of adult ideology and events transpiring at the youthful grassroots as the ideal methodological approach, well knowing that the attempt to understand youth organizations on the basis of the youth cultures inherent to them can quickly reach its limits in actual scholarly practice.[15] The challenge begins with the sources. In general, those used to reconstruct the worlds inhabited by children and young people are much harder to track down than records pertaining to the programmatic aims and objectives of organizers or the practices of individual educators and caregivers. The relative voicelessness of young people in the archives has led some historians of childhood to see parallels between their subjects and other marginalized groups and hence to utilize postcolonialist approaches in their attempts to lend these underage protagonists voice.[16]

![Members of the Hitler Youth at a demonstration, autumn 1943, Photographer: unknown. Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-J08403,_Hitlerjungen,_als_Helfer_bei_Luftangriffen_verwundet.jpg#/media/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-J08403,_Hitlerjungen,_als_Helfer_bei_Luftangriffen_verwundet.jpg Bundesarchiv Bild 183-J08403 (ADN) / Wikimedia Commons], license: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en CC BY-SA 3.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/3562.jpg)

While critiques of Eurocentric concepts of adolescence and childhood are surely warranted, postcolonial analogies become problematic at the very latest when theories of subaltern resistance are unthinkingly applied to age groups or stages of development that are transitory by definition. So as not to fall into the “agency trap” identified by Mona Gleason, it is advisable to take a broader view of the contributions of children and adolescents in youth organizations, namely along a dynamic continuum “from opposition to assent,” as Susan Miller has aptly put it.[17] Miller pleads for an undogmatic and elastic concept of agency. Only in this manner can the manifold options open to organized youth vis-à-vis their leaders be presented in such a way that research narratives take into account both their situational cooperation and their occasional breaking rank, not to mention the zeal and fanaticism which found their most extreme expression in the militant Hitler Youth or the orgies of violence of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.[18]

Marching youth: Civic education in war and peace

The search for traces of youthful Eigensinn was certainly not a feature of the early critical scholarly investigation of organized youth, which relied heavily at first on the many self-testimonies of former members. Only gradually, after World War II, did this perspective emerge, then more explosively in the 1970s under the influence of contemporary youth countercultures, the student movement first and foremost. In times of antiauthoritarian protest, youth was a new and volatile political force that, depending on its orientation, could serve to stabilize or destabilize social power relations. Precisely this double character of youth as a demographic resource and sociopolitical risk, which adult authorities sought to minimize through new institutions of subjugation such as juvenile law, youth welfare or hierarchically organized youth leagues, formed the central analytical framework for the first generation of historians devoted to the investigation of youth organizations.[19]

Numerous representatives of this generation of researchers, some of whom had been exposed to antiauthoritarian theories, interpreted youth organization primarily as the long arm of ruling elites. Control, disciplining and indoctrination were the reigning paradigms. The principle of bringing together and controlling young people is most evident in the seminal works on fascist and Nazi recruiting organizations.[20] These historians sought to show how organizations like the Italian Opera Nazionale Balilla and the German Hitler Youth were completely brought in line with the prevailing dictatorship, disavowing each child’s democratic right to a good education in favor of the claim of the national community to profit from a militarized youth that was willing to make sacrifices. They paid particular attention to the close alliance between youth organizers and the respective authorities, to internal mechanisms of surveillance and punishment, as well as to the premilitary character of extracurricular and secular concepts of education in modern mobilization dictatorships.[21] Historical research on the actual worlds of experience of young people, on the other hand, is still in its infancy. To be sure, despite rising membership rates in the 1930s the Hitler Youth and the League of German Girls failed in their aim of “total education” of an entire generation. With the exception of a few oral history projects, in which contemporary witnesses report on their experiences as young Nazis on group outings, in marching bands and during premilitary training, there are barely any studies offering an in-depth look at the motivations of young members.[22]

The persecution of marginalized, especially Jewish and other “non-Aryan” children and young people later became an additional research focus. Opportunism and opposition in daily life – as in the case of the Swing Youth – were hardly addressed in early studies, however.[23] The main emphasis was understanding youth in one-party states like the Third Reich and Maoist China where children denounced their parents as counterrevolutionaries, as minors led astray or as inmates of “total institutions.”[24]

The assessment was somewhat more ambivalent regarding civic education in liberal and socialist youth organizations, though here the official ideologies of the respective organizational elites served as the benchmark. The Cold War competition between systems was clearly reflected in initial interpretations, especially those propagated by the organizations themselves. These include Scotsman John S. Wilson’s world history of the Scouting movement published in the late 1950s and emphasizing the voluntary and religious character of the Scouts as a “bulwark of liberty” against the state-controlled “columns” of communist-atheist-raised youth in the East.[25] This bipolar thinking also informed the depictions on the other side. Thus, the regime-conformist historical studies of the Free German Youth (FDJ) were rarely free of politically motivated potshots against the youth organizations of NATO states, which were rudely dismissed in typical Marxist-Leninist fashion as “breeding grounds of Western imperialism.”[26] Such enemy stereotypes were a guiding force behind educational objectives such as the “socialist personality” or the “communist individual,” adopted by the Party youth of member states of the later Warsaw Pact after 1945. Hegemonic Marxist-Leninist parties demanded that their young generation perform their work duties, commit themselves to building a just society and show solidarity with the independence efforts of colonized peoples, or so Walter Ulbricht, chairman of the Socialist Unity Party of the GDR, declared in 1958. In exchange they offered Party-loyal young people new forms of participation and undreamed-of prospects of career advancement, especially in the postwar years when new recruits were lacking.[27]

![Recruiting poster, Junge Union Bayern 1980. Author: unknown. Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KAS-Mitgliederwerbung-Bild-13204-1.jpg Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Bild-13204 / Wikimedia Commons], license: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en CC BY-SA 3.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/3561.jpg)

The enlisting of new members, which coupled political-ideological schooling with promising careers in politics, was ultimately also a core activity of political parties in Western countries after 1945, albeit under the banner of pluralism. In the newly founded Federal Republic of Germany it was the Young Union (Junge Union) of the conservative Christian CDU, the Young Socialists (Jungsozialisten) of the social-democratic SPD and the Young Democrats (Jungdemokraten) of the liberal FDP in particular which, sometimes building on the work of their predecessors during the Weimar Republic, shaped the forms of mobilization and the opportunities for participation available to young people and adults in the West German party system. A key difference to non-partisan youth organizations was their age structure. Though party youth comprised people of various ages, their leadership ranks were mostly occupied by members between the ages of 25 and 35, a trend that continues into the present. Historian Wolfgang R. Krabbe attributes the semantic elasticity of the concept of youth in the context of political youth organizations, which consciously cater to young adults as well, to the fact that the latter serve numerous purposes. Historically they have alternately acted as “recruiting depots,” “training and electoral assistant teams of the mother parties,” “candidate reservoirs” and even as “party-internal opposition groups.”[28] As of the 1970s, the last aspect in particular cemented the reputation of party youth as critical supporters with a “passion for lively debate” who acted beyond party lines as lobbyists of the young generation and denounced the “predominance of seniors” in parliament and government.[29]

Beyond these institutional histories there exists especially in North America and Western Europe a historiography rooted in social history and that addresses youth organizations as testing grounds for critical modernization theories. Class-oriented analyses linked the emergence of Scouting in Britain and America with the communication of patriotic ideals within bourgeois hierarchical structures along with the attempt to marginalize proletarian youth cultures or even stigmatize them as a revolutionary threat. In the discourse of degenerate and delinquent working-class children, there emerged an understanding of anti-delinquency coupled with the notion of political prevention. Youth organizations replaced punitive measures and open repression with playful forms of national-political cooptation in order to re-educate “problem youth” into loyal citizens.[30] The specter of a frivolous youth-oriented culture of consumerism and recreation developing in East and West as of the 1950s served these organization as a bogeyman.[31] Concerns about the supposed excesses of rebellious teenagers escalated into so-called moral panics.[32] Which is not to say that youth culture and youth organizations were incompatible in general. Rather, the image of many organizations transformed over the decades precisely because of the cultural predilections of many young people, who brought their music, clothing styles and manners along with them on camping trips and to summer camp. In general, young people in liberal Western societies had ever greater opportunities for personal development. Even the SED regime, despite all its didacticism, was willing to make concessions in the 1960s, accommodating the changing recreational needs of young people with regard to cultural imports from the West. The sounds of modern rock and pop music could henceforth be heard in East German houses of culture and FDJ youth clubs.[33]

Few historians went as far as American Michael Rosenthal, who imputed protofascist tendencies to conservative youth leaders like Baden-Powell.[34] But most agreed with Rosenthal’s assertion that the focus on system differences often served to disguise more than it revealed. Though these methodologically sophisticated studies rarely went beyond the national framework of their protagonists, they did bring to light a number of commonalities. Accordingly, youth organizations of various stripes shared not only the same rhetoric of camaraderie and youthful fellowship, they also formed the vanguard of a modern form of biopolitics spanning ideologies – from the regeneration of old empires to the totalitarian utopia of the “New Man” – that pursued the optimization of individual and collective bodies believed to be in competition.[35]

Precisely the transnational reach of uniformed youth – their soldierly chants, oaths of allegiance and torchlight processions – resulted in early points of contact with research on militarism and total war. These overlaps were significant if only because they led to a redefinition of the role of adolescents in the industrialized mass wars of the twentieth century. Purely victimizing narratives gave way to more complex ones, in which children and young adults appeared as key war-related actors in national and imperial mobilization efforts.[36] Emphasis was placed on the emotional value of propagandistic representations in which allegories of children symbolized the will to combat as well as the vulnerability of one’s own nation.[37] On the other hand youth organizations made a fundamental contribution to the premilitary training of their recruits by defining age-appropriate areas of activity, generally in cooperation with the military and government. Depending on the age group, gender and level of totalization of the conflict, these activities ranged from minor assignments on the home front to combat deployment as “child soldiers.” The militarization of children and adolescents was by no means limited to “hot” wars. The home-front character of state-supporting youth organizations was evident during the Cold War, with uniformed minors on both sides of the Iron Curtain monitoring airspace, building shelters, and simulating survival under nuclear attack.[38] Here too, in consulting the latest research, the commonplace notion of children as victims does not do justice to reality. Not to be underestimated is the significance of war as a rite of passage in which young people take part consciously, whether to flee a poverty-induced lack of perspectives or because of peer cultures propagating ideals of loyalty and heroism and pressuring them to take up arms.[39]

Gender roles and sexuality

With the introduction of gender theories into historiography there was a growing realization that behind all the talk of a New Man – led by a mentally and physically vigorous youth – lurked a social debate over a new concept of masculinity.[40] This is evident not only in the convergence of the cult of personality and the cult of youth characteristic of the early twentieth century. Another decisive aspect was that many contemporary youth organizations, in which state leaders – from Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919) to Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) and Josef Stalin (1878-1953) – were revered as vigorous, energetic and eternally young, strove for the remasculinization of supposedly “slackening” societies.[41] This was the conclusion of Anglo-Saxon historians in particular, who were not satisfied with the notion that the turn towards youth before World War I was the result of a general civilizational malaise brought on by advancing industrialization and urbanization. The crisis of the bourgeois gender order became the focus of works by Robert MacDonald, Gail Bederman and Clifford Putney.[42] All three scholars saw the rise of male-dominated Boy Scouts as a reaction to the supposed threat of the feminization of public life symbolized by working women and female emancipation movements. This explained the tendency towards rigid gender segregation. The aim was to produce good citizens and real men.

To what extent the desire for a homosocial community, as formulated by the Boy Scouts and later by fascist youth leaders, was proof of a reactionary antimodernism has been the subject of controversial debate. Indisputable is the fact that the insistence on male exclusivity was an integral part of bourgeois gender policies which, by repressing women and restricting them to the domestic sphere, hoped to regenerate hegemonic masculinity and hence the masculinity of politics and the state. At the same time, gender-history studies emphasize the transformation of notions of masculinity and processes of manhood in high modernity.[43] Youth organizations responded to increasing demands in the male-coded fields of the economy and science by diversifying their educational programs, which increasingly paired survival training in the outdoors with basic technical and mechanical skills, though not in any uniform manner. The recreational activities of American Boy Scouts in the 1920s were geared towards the needs of a competitive capitalist society, whereas the Soviet Komsomol endeavored to accelerate the building of communism. Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870-1924) expected young Soviet citizens to consciously develop into “vanguards of the proletariat” in the years following the October Revolution, with no regard for family ties or bourgeois notions of morality in their “manly struggle” for a new order.[44] Despite their different policy aims, both systems – the liberal and the communist – were concerned with molding young male citizens who could wield an ax and flint just as well as modern technologies.[45]

Other researchers, on the other hand, detected in the Cowboy and Indian games of white Boy Scouts and Hitler Youth a rough-and-ready primal style of masculinity once considered the exclusive reserve of “uncivilized” non-White men.[46] Leading youth organizations in Europe and North America not only fought the “coddling” of the Victorian bourgeoisie and every form of female interference, in many cases they also reproduced colonial and racist hierarchies. They were phenotypically and culturally “white” in the literal sense of the word. Training in manhood could be integrative and exclusionary at once. At no point were all boys welcome, but only those who satisfied the respective prevailing criteria of, e.g., the Volksgemeinschaft (national community) in Nazi Germany, Jim Crow laws in the American South, or antibourgeois ideals in Bolshevist Russia. This interpretation makes youth organizations interesting for historical intersectionality research, which starts from the assumption that processes of gendering, racialization and social hierarchization are entangled.[47]

Even the most reactionary educators did not question the value of a nature-loving education for girls that promoted physical fitness, even though the measure of success was its capacity to limit women and girls to domestic and reproductive tasks. Among the merits of historical women’s and gender studies in recent decades is its having overcome this polarity and shown in which contexts certain youth organizations have tolerated or even specifically promoted a multitude of modern femininities. The League of German Girls might serve as an example to show how inconsistent these femininities could be. The recreational and training opportunities of the Nazi girls’ organization offered the daughters of varied social strata the chance to escape the confines of family life. Yet the emphasis on physical exercises and female self-leadership disguised a reactionary ideal of women that limited young women to the role of healthy, attractive and devoted “German mothers.”[48]

Communist youth leagues in Europe and North America understood themselves as a classic foil to the bourgeois ideology of “separate spheres.” In the Soviet Komsomol and the considerably smaller Young Pioneers of the Communist Party of the U.S.A. the commitment to gender equality was part of a revolutionary agenda as early as the interwar period, viewing youth as more malleable and enthusiastic than adults and assigning them a key role in building a new society. Communist party leaders took pains to ensure that girls and young women were in no way treated as inferior to their male counterparts in their work assignments, at political demonstrations and cultural events, in literacy campaigns and at sporting events in summer camps.[49]

But the same historians investigating these coeducational traditions have warned about interpreting these activities as a practice ground for progressive feminist identities. The supposed revolutionizing of gender relations under communism did not usually mean that the masculinity of the body politic and hence the predominance of males in politics, the economy and military were ever seriously called into question. The ideals of discipline, camaraderie and self-sacrifice prevailing in organizations that toed the party line remained as male-coded as ever. The charged relationship between conservative and progressive gender roles is just as pronounced in the female equivalents of these youth organizations in the Anglo-Saxon world: the Girl Scouts in the United States and the Girl Guides in the British Empire. The Girl Scouts, founded in 1912 by Juliette Gordon Low (1860-1927), sought to distinguish themselves from the somewhat older Campfire Girls, which Low rejected as too traditionalist in their understanding of what girls should aspire to. Low created the alternative concept of a community of experience for girls and women in which patriotism, athletics and conservationism were melded with classic female virtues like housekeeping and child-rearing. This ambivalence was both politically intentional and strategically necessary, since the uniformed Girl Scouts were initially perceived as a provocation by their male colleagues.[50]

![Girl Scouts, April 1958. Photographer: Adolph B. Rice Studio, Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Girl_Scouts_(2899346014).jpg The Library of Virginia @ Flickr Commons / Wikimedia Commons]](sites/default/files/import_images/3563.jpg)

An all too rigid notion of youth organizations as the staging ground for modern gender struggles begins to unravel, however, when we shift the perspective to young people themselves. Anecdotal evidence suggests that in the early phase of the English Scouting movement girls reacted just as enthusiastically to Baden-Powell’s initiative, forming their own Scouting troops alongside or even together with boys. Baden-Powell was reportedly deeply unsettled when he encountered girls who claimed they were Scouts at the first major Scouting convention held in the Crystal Palace in London in 1909. Since his concept of Scouting was aimed at boys, Baden-Powell eventually entrusted his sister Agnes (1858-1945) with the task of founding the Girl Guides.[51] Accounts from young people in other contexts likewise suggest that they often saw no contradiction in terms between their desire for homosocial exclusivity and their sexual socialization. To put it more bluntly, there was no less flirting going on between Girl and Boy Scouts, between Hitler Youth and League of German Girls members than there was among their non-organized peers.

More fruitful investigations of gender in youth organizations therefore need to look at more than the construction of gender roles in official discourse, and generally need to include the communication of sexual morals – from the virtuousness of premarital abstinence to instructions in correct, state-sanctioned reproductive behavior.[52] Just as indispensable is the need to look at instances where these norms were intermittently transgressed through forms of youthful appropriation and experimentation.

The sexual abuse of minors in youth organizations, a problem hitherto woefully overlooked by historians, shows just how close harmless intimacy and sexual assault can be. The lack of research on this topic may be due to nonexistent or hard-to-access sources, but certainly also to the reservations of historians to take on the more thorny dimensions of homosocial communities, particularly when children are involved. A disturbing picture was offered by the “perversion files” of the Boy Scouts of America, released in 2012 by order of the Oregon Supreme Court. According to these documents, the organization covered up thousands of cases of sexual abuse over a period of decades, protecting pederast leaders who molested and raped young boys entrusted to their care.[53] Comparing these violent crimes with the endorsement of premarital sex, as propagated by some Nazi youth leaders,[54] may seem rather presumptuous. It is fair to assume, however, that these are merely two of many manifestations of the fatal triangle of power, coercion and sexuality at work in youth organizations which historians have yet to uncover.

Youth without borders? Transnational and global perspectives

New approaches in global history are increasingly marked by their calling attention to the complementarity of various spatial orders. Whereas previous methodological and theoretical discussions focused on transnational and/or global paradigms superceding seemingly obsolete nation-state perspectives, more recent research has emphasized the simultaneity and hence complementarity of national, transnational, continental and global spheres of action serving as an analytical framework. This section will show why the history of organized youth is a worthwhile subject of investigation for historians with a view to such overlapping frameworks – that is to say, where historical actors repeatedly relate their actions and activities to transregional processes, no matter if these actors mostly operate at the local level.

Analytically, it is important to distinguish between two processes: the globalization of concepts and models of organized youth and the transnational mobility of organized youth. Earlier studies pointed out that prominent mass organizations such as the Soviet Komsomol and the Boy Scouts of America were internationally networked. Their attention was usually focused, however, on the forms and speed of geographical expansion. It is an indisputable fact that Young Pioneers and communist youth in Europe and North America in the years following the October Revolution, and later in Africa and Latin America, had close ties to Moscow and officially endorsed the Soviet Union’s claim to leadership with regard to propagating the principles of proletarian internationalism.[55]

Thinking in terms of center and periphery also held sway in the Scouting groups of that period. Regardless of whether the Scouts’ rhetoric of brotherhood served in their own eyes to further the interests of imperial renewal or to foster international understanding, most commentators viewed it as the expression of an Anglo-Saxon project of world integration.[56] The foreign contacts of fascist organizations are proof of the widespread willingness of these organizations to enable international youth encounters. Relations between the Hitler Youth and the Italian Opera Nazionale Balilla have been relatively well researched, revealing the subsequent knowledge transfer between these two organizations as well as offering a vision of the future in which this Fascist Internationale was to serve as the framework for a new nationalist Europe.[57]

Recent scholarship has paid more heed to the political demonstrations and mobilization campaigns which young people used in the decades after World War II to influence Europeanization processes. Historian Christina Norwig speaks in this context of the “first European generation” to insist in an idealistic and energetic way – often in close cooperation with transatlantic interest groups and national politicians – on the federal unification of (West) European states. The European Youth Campaign of the 1950s formed the spearhead of a transnational movement, which in conjunction with about 500 youth organizations was intended to inspire adolescents to work for a unified but decidedly anticommunist Europe through participation in seminars, evening discussions, study tours and youth parliaments.[58] The Cold War offered a decisive though not an exclusive framework “from below” for such European policy initiatives. This could be sidestepped in isolated cases, as shown by the example of young Catholic expellees in the Federal Republic of the 1960s who, despite being embedded in a national framework, intensified their contacts with young Christians in the regions they came from and called for reconciliation with their East European neighbors.[59]

Power asymmetries and centrifugal forces played an important role in disseminating certain organizational concepts. Newer studies, however, question the conventional dichotomy of active-exporting and passive-receiving societies, pointing to processes of creative reception and selective adaptation. Local elites seldom adopted imported structures wholesale, but adapted them to familiar religious, cultural and political norms. This was true of a range of Jewish-Zionist youth groups, in which wider social and specifically Jewish influences intermingled.[60] American communists made concessions to the cultural mainstream, using baseball tournaments and Wild West themes to help recruit working-class children from various ethnic backgrounds.[61] The Scouts in Catholic Poland and Hungary lost their Protestant tinge and combined males and females under their respective umbrella organizations.[62] These national idiosyncrasies harbored enormous conflict potential, which in transnational forums of organized youth repeatedly led to tensions and misunderstandings. At the third International Scout Jamboree in Copenhagen in 1924, for example, Latin American Scouts complained about the hegemonic claims of their “brothers” to the north, whose civil-religious Protestantism was in their view not compatible with the Catholic orientation of their Hispanic organizations. The presence of Girl Scouts, on the other hand, at international Scouting camps sometimes made Anglo-American Boy Scouts uneasy, supporting as they did the segregation of boys and girls in their organizations.[63]

These institutional models originating in Europe and North America underwent even more local adaptations in the non-Western world. Whereas the symbolic worlds of Western youth organizations were saturated with imperialist metaphors of reconnaissance and conquest, hybrid forms increasingly developed in Africa, South and East Asia. Originally introduced to stabilize colonial rule, organizations like the Scouts were capable of accommodating enough local characteristics to also make them attractive to anticolonial liberation movements. Ho Chi Minh (1890-1969), at whose behest the Vietnamese Young Pioneers were founded in 1942, was not only an avowed communist but also a disciple of Baden-Powell’s concept of mobilization.[64] The boundaries between bourgeois, communist and fascist influences were just as fluid in the first Chinese youth organization. The Nationalist Youth Corps under Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975) adopted elements of the British Boy Scouts while extolling the merits of premilitary training of the kind given to young people in Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany.[65] In South Africa, efforts to indigenize European-imperialist forms of youth leadership resulted in the founding of the African National Congress Youth League in 1944, which soon developed into a cadre factory for anticolonial nationalists.[66] Hence political ideologies could potentially hinder the global diffusion of youth organizations but didn’t necessarily do so.

![“On July 28, 1957, during his official sojourn to the German Democratic Republic, the president of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh, paid a visit with his entourage to the ‘May Day’ agricultural cooperative in Tempelfelde (Bernau District), the machine and tractor station in Werneuchen by Bernau, and the ‘Helmuth Just’ Pioneer camp on Wukensee lake near Biesenthal” (original ADN caption), July 28, 1957. Photographer: Horst Sturm. Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_183-48550-0036,_Besuch_Ho_Chi_Minhs_bei_Pionieren,_bei_Berlin.jpg Bundesarchiv Bild 183-48550-0036 / Wikimedia Commons], license [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en CC BY-SA 3.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/3564.jpg)

Globalization not only resulted from informal transfers but was specifically laid out by organizers in the framework of transnational institutions created for this very purpose. This began with the World Scout Jamborees, which generally took place four times a year as of 1920 and by the end of World War II encompassed seventy nations and five continents. By fashioning themselves as peace festivals and attracting a range of world leaders, the World Scout Jamborees became global media events and had a formative influence on a range of other transnational youth gatherings, including the socialist World Festival of Youth and Students and the Catholic World Youth Day. Despite all the rhetoric of brotherhood, these gestures of youth fraternization concealed specific, particularist interests. World Jamborees paired youthful idealism with reactionary forces keen on maintaining the status quo. In the public eye, the Scouts remained a boys’ club and non-Western Scouts were second-class youth.[67] Racial segregation in the United States and South Africa led in both these societies to separate Boy Scout units for blacks and whites, the former being barred from participating in World Scout Jamborees into the second half of the twentieth century – in the case of South Africa until the end of the Apartheid regime in the early 1990s. An open question is to what extent the first Pan-African jamborees in the 1960s under the influence of decolonization were perceived by contemporaries as a direct challenge to the global institution of Scouting hitherto under the sway of colonial rulers.[68]

The World Festivals, which defined themselves against “imperialist” Scouts, were for their part hardly egalitarian events. While their communist organizers declared their solidarity with the colonized world, the festivals themselves had a marked paternalist view of the countries of the “Third World,” which they perceived as needy and “underdeveloped.”[69] The simultaneity of youthful “anti-imperialism” and a European-socialist claim to leadership became apparent in 1973 at the 10th World Festival of Youth and Students in East Berlin, described by some participants as a “Red Woodstock.” While groups of young people engaging in discussion on Alexanderplatz and upbeat musical groups from Asia, Africa and Latin America lent the festival an image of freedom-loving inclusivity, putting these “mini-freedoms” on display was of a piece with the propaganda objectives of the SED regime. This included underscoring the moral superiority of the socialist system in tackling development-policy challenges in the global South.[70] To what extent the talk of solidarity at the World Festivals formed the vanguard of a new socialist world policy expressed in the economic and military commitment of individual Warsaw Pact states in the second half of the 1970s – e.g., in 1976 in Angola or in the 1977-78 Ogaden War between Somalia and Ethiopia – still needs to be addressed by scholars.

Such contradictions were overarched by the discourse of youth as a revitalizing and purifying force which during the course of the twentieth century extended into the very semantics of international relations. According to anthropologist Liisa Malkki, the campfire diplomacy of the Scouts, where members from all around the world gathered under the open sky to profess their will to peace and reconciliation, was the expression of a transideological symbolic and metaphorical language that alternately described children and young people “(1) as embodiments of a basic human goodness (and symbols of world harmony); (2) as sufferers; (3) as seers of truth; (4) as ambassadors of peace; and (5) as embodiments of the future.”[71] In order, however, for this metaphorical universal weapon to catch on there had to be more than a general social consensus on the political value of youth. Young people themselves had a significant stake in the articulation of utopian world orders, developing their own unique practices of international communication in the process.

The rise of young people as the avant-garde of globalization beginning in the 1920s and gaining new momentum in the 1950s and 1960s was conditional on material and cultural factors. Technologization, medialization and increased mobility expanded communication networks and the possibilities of cross-border exchange. Youth with free time, financial resources and access to scholarships and grants took part in student exchange programs, traveled foreign countries, slept in youth hostels and sought contact with backpackers from other parts of the world. Richard Ivan Jobs, in a recent monograph, even describes backpacking as a genuine practice of international understanding among youth, one which in his view decisively promoted European integration “from below” in the decades following World War II.[72] “Young” and “youthful” became distinguishing characteristics of new transnational communities that broke with the seemingly outmoded conventions of older generations.[73] While the intergenerational character of youth organizations limited the pathological perspective of age as an expression of weakness and infirmity, organized youth did sometimes cultivate a scolding attitude towards older generations and emphasized their aversion to established policies, which they chided as scheming and insincere. Those wanting to experience true friendship between nations, claimed American Boy Scout Owen Matthews in 1936, should steer clear of the bureaucrats in the League of Nations and go to jamboree bonfires instead, where brotherhood devoid of all cynicism and egotism was not merely preached, but practiced by young people from five continents.[74]

In reality this cult of the authentic was fractured, as shown by recent research. Instead of leveling differences, international youth gatherings could just as easily reproduce them. A joint work camp in Algeria in the summer of 1964 with young socialist volunteers from Eastern Europe, the Middle East and China foundered on language barriers and brought international rivalries to the fore that were hardly compatible with the ideal of proletarian internationalism.[75] Many Scouts from war-torn and economically disadvantaged European nations felt snubbed in the 1920s and 1950s by their comrades from the United States, who strutted across the jamboree campgrounds with their fancy cameras and radios. The result was anti-American slanders. Things got downright rowdy between delegates from Poland and Lithuania in the Dutch village of Vogelenzang in 1937, where a quarrel over the border between these two countries ended in a ferocious brawl.[76] The sisterhood of Girl Scouts also had a hard time emancipating itself from national and imperial patterns of order. As Kristine Alexander recently noted, it was not uncommon for Canadian and British Girl Guides and their leaders to utter disparaging comments about their Indian sisters.[77]

A paradox becomes evident here, one previously pointed out by globalization theorist Roland Robertson. Whenever young people in these organizations sought a sense of belonging in a politically mapped out and subjectively experienced “world” of any sort, the process could just as easily backfire and end up reinforcing more narrow particularist identities.[78] The spatial broadening of one’s own horizon of socialization was often less conducive to overcoming local identities and national loyalties than it was to entrenching them. The latter played into the hands of social and state elites, who feared nothing more than the subversive potential of youth communitizing according to purely generational criteria. The image of children and young people as carefree internationalists persisted nonetheless for long periods of the twentieth century because of the benefits it entailed. It gave young people social prestige, a public voice and opportunities for social advancement within a given system. It gave older people the opportunity to jettison the moral burdens of the past and depict one’s own camp as cosmopolitan, future-oriented and sustainable.

![XII Boy Scout World Jamboree - Farragut State Park, Idaho, August 1967. Copyright: pieshops@gmail.com. Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:XII_Boy_Scout_World_Jamboree_-_Farragut_State_Park,_Idaho_(6195799522).jpg Wikimedia Commons], license: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en CC BY-SA 2.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/3565.jpg)

Quo vadis, organized youth?

A closer look at the historiographical literature of recent decades on the phenomenon of organized youth reveals an imbalance. While no master narrative of the twentieth century can fail to acknowledge the millions of uniformed Hitler Youth and Komsomols, in general the topic tends to be sidelined in contemporary history debates. The reasons for this discrepancy probably have less to do with the profession’s growing specialization than with the fact that more recent research on youth organizations is only loosely associated with the prevailing methodological approaches and paradigms. To put it another way, individual studies have made original contributions to the working areas of gender history, global history and the history of childhood without being rooted in these fields.

Added to this is the problem of periodization, which only exacerbates this attention deficit. Historians simply disagree about which timeframe to apply. If the focus is on continuities between older men’s clubs and modern youth organizations, it is conceivable to start in the mid-nineteenth century with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) or even further back, say, with the Free Masons. The wave of liberalization during the 1970s lends itself as an incisive turning point, when youth and countercultures increasingly fused and organizations with longstanding traditions such as the Boy Scouts of America lost nearly half their membership. For American sociologist Robert Putnam, dwindling membership numbers are proof of the downfall of a conservative culture of “civic engagement” and a consumerist turn to the private sphere.[79] But there are other causes as well, such as sinking birthrates in Western societies and the emergence of competing spaces of socialization, e.g., the expansion of youth work in athletics associations or the anti-authoritarian youth-center movements that proliferated in the Federal Republic after 1968.[80] Even more spectacular was the erosion of organized youth leagues in the former Eastern-bloc states after the end of the Cold War, as communist regimes and the state youth groups they controlled literally collapsed. Yet the supposed swansong of organized youth is somewhat premature, as evidenced by the marches of rightwing youth groups and their links to nationalist movements in Europe, Russia and North America in the early twenty-first century. It is likewise clear that non-Western youth organizations, which to date have rarely been the subject of empirical studies, follow entirely different chronologies. Discussion is surely warranted about whether jihadism of the early twentieth century is sufficiently described as an equally anti-Western and rightwing-radical youth movement.[81]

What research deficits remain? The as yet unwritten global history of organized youth would certainly be a mammoth undertaking. A viable starting point for a work of this sort would be those places where the level of networking was highest, that is to say the transnational transfer and local adaptation of certain organizational cultures and the actors who enabled this. Moreover, there is much to be said for comparative studies which analyze development dynamics, communitization processes and practices of exclusion among organized youth leagues in various regions of the world. A worthwhile focus of future research would undoubtedly be the spread of youth movements to rural regions, where youth organizations achieved a higher penetration rate than they did in urban centers with their more informal forms of socializing among young people. Another interesting topic, one that would essentially turn historiography on its head, would be the question of to what extent youth organizations not only functioned as educational institutions for young people but also as forums of rejuvenation, serving to regenerate “aging” nations and empires. The road here lies open.

Translated from the German by David Burnett.

Recommended Reading

Mischa Honeck, Youth Organizations, Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 16.5.2019, URL: http://docupedia.de/zg/Honeck_youth_organizations_v1_en_2019

Copyright (c) 2023 Clio-online e.V. und Autor, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <redaktion@docupedia.de>

References

- ↑ Richard Etheridge, Walking in the Shadow of a Political Agitator: Book 1: Apprentice, London 2016, pp. 77-78. On the “Red Scouts” affair in 1950s Britain, see Sarah Mills, “Be Prepared: Communism and the Politics of Scouting in 1950s Britain,” in: Contemporary British History 25 (2011), no. 3, pp. 429-450.

- ↑ For a synthesis, see Bodo Mrozek, “Jahrhundert der Jugend?” in: Martin Sabrow/Peter Ulrich Weiß (eds.), Das 20. Jahrhundert vermessen: Signaturen eines vergangenen Zeitalters, Göttingen 2017, pp. 199-218.

- ↑ Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991, London 1994.

- ↑ Detlev J.K. Peukert, Jugend zwischen Krieg und Krise: Lebenswelten von Arbeiterjungen in der Weimarer Republik, Cologne 1987, p. 304. Peter Dudek, Geschichte der Jugend, in: Heinz-Hermann Krüger/Cathleen Grunert (eds.), Handbuch Kindheits- und Jugendforschung, Opladen 2002, pp. 333-349, here p. 333, comes to a similar conclusion.

- ↑ Josef Ehmer, “Das Alter in Geschichte und Geschichtswissenschaft,” in: Ursula M. Staudinger/Heinz Häfner (eds.), Was ist Altern(n)? Neue Antworten auf eine scheinbar einfache Frage, Berlin/Heidelberg 2008, pp. 149-172; Steven Mintz, “Reflections on Age as a Category of Historical Analysis,” in: The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 1 (Winter 2008), no. 1, pp. 91-92; Leslie Paris, “Through the Looking Glass: Age, Stages, and Historical Analysis,” ibid., pp. 106-113.

- ↑ Richard Ivan Jobs/David M. Pomfret, “The Transnationality of Youth,” in: idem. (eds.), Transnational Histories of Youth in the Twentieth Century, New York 2015, pp. 1-19, here p. 5.

- ↑ Granville Stanley Hall, Adolescence: Its Psychology and its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education, 2 vols., New York 1905.

- ↑ See Yonatan Eyal, The Young America Movement and the Transformation of the Democratic Party, 1828-1861, New York 2007; Anthony Esler (ed.), The Youth Revolution: The Conflict of Generations in Modern History, Lexington, MA, 1974.

- ↑ On the paramilitary Boys’ Brigades, see John R. Gillis, Youth and History: Tradition and Change in European Age Relations, 1770-Present, London 1974, pp. 130, 145. On the Woodcraft Indians, which organized nature games following the example of native Americans, see Philip Deloria, Playing Indian, New Haven 1998, pp. 95-127.

- ↑ See John Springhall, Youth, Empire, and Society: British Youth Movements, 1883-1940, London 1977; David I. Macleod, Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA, and their Forerunners, Madison, WI, 1983.

- ↑ Jay Mechling, “Children in Scouting and Other Organizations,” in: Paula S. Fass (ed.), The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World, New York 2013, pp. 419-433, here p. 428.

- ↑ See Sigried Bias-Engels, Zwischen Wandervogel und Wissenschaft: Zur Geschichte von Jugendbewegung und Studentenschaft, 1896-1920, Cologne 1988; Winfried Speitkamp, Jugend in der Neuzeit: Deutschland vom 16. bis zum 20. Jahrhundert, Göttingen 1998, pp. 118-161, online at http://digi20.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb00044409_00001.html.

- ↑ Tim Jeal, Baden-Powell, New Haven 2001, pp. 457, 493, 545; Michael H. Kater, Hitler Youth, Cambridge, MA, 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Walter Laqueur, Young Germany: A History of the German Youth Movement, New York, 1962, p. xv.

- ↑ See, for example,Tamara Myers, “Local Action and Global Imagining: Youth, International Development, and the Walkathon Phenomenon in Canada,” in: Diplomatic History 38 (April 2014), pp. 282-293; Sian Edwards, Youth Movements, Citizenship, and the English Countryside: Creating Good Citizens, 1930-1960, London 2017; Olga Kucherenko, Little Soldiers: How Soviet Children Went to War, 1941-1945, New York 2011.

- ↑ See, e.g., Kristine Alexander, “Can the Girl Guide Speak? The Perils and Pleasures of Looking for Children’s Voices in Archival Research,” in: Jeunesse: Young People, Texts, and Cultures 4 (2012), no. 1, pp. 132-145, online at http://jeunessejournal.ca/index.php/yptc/article/view/154/111; Joanne Faulkner, Young and Free: (Post)Colonial Ontologies of Childhood, Memory, and History in Australia, Lanham, MD, 2016. On the role of postcolonial approaches in research on the history of childhood, see also the Docupedia article of Martina Winkler, Kindheitsgeschichte, Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, Ocotber 17, 2016, http://docupedia.de/zg/Winkler_kindheitsgeschichte_v1_de_2016.

- ↑ Mona Gleason, “Avoiding the Agency Trap: Caveats for Historians of Children, Youth, and Education,” in: Journal of the History of Education 45 (2016), no. 4, pp. 446-459; Susan A. Miller, “Assent as Agency in the Early Years of the Children of the American Revolution,” in: The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 9 (Winter 2016), no. 1, pp. 48-65, here p. 49.

- ↑ See Daniel Leese, Die chinesische Kulturrevolution, 1966-1976, Munich 2016, pp. 39-56.

- ↑ For representative examples, see Laqueur, Die deutsche Jugendbewegung; Felix Raabe, Die Bündische Jugend: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Weimarer Republik, Stuttgart 1961; Heinz S. Rosenbusch, Die deutsche Jugendbewegung in ihren pädagogischen Formen und Wirkungen (Quellen und Beiträge zur Geschichte der Jugendbewegung, vol. 16), Frankfurt a.M. 1973.

- ↑ See Arno Klönne, Hitlerjugend: Die Jugend und ihre Organisation im Dritten Reich, Hannover/Frankfurt am Mai 1955; Carmen Betti, L’Opera nazionale Balilla e l’educazione fascista, Florence 1977.

- ↑ See, e.g., Hannsjoachim W. Koch, Geschichte der Hitlerjugend: Ihre Ursprünge und ihre Entwicklung, 1922-1945, Percha 1975; Michael Buddrus, Totale Erziehung für den totalen Krieg: Hitlerjugend und nationalsozialistische Jugendpolitik, Munich 2003; Ute Schleimer, Die Opera Nazionale Balilla bzw. Gioventu Italiana del Littorio und die Hitlerjugend – eine vergleichende Darstellung, Münster 2004. Newer perspectives are offered by Kathrin Kollmeier, Ordnung und Ausgrenzung: Die Disziplinarpolitik der Hitler-Jugend, Göttingen 2007; Till Kössler, “Die faschistische Kindheit,” in: Meike S. Baader/Florian Eßer/Wolfgang Schröer (eds.), Kindheiten in der Moderne: Eine Geschichte der Sorge, Frankfurt am Main/New York 2014, pp. 284-318; Thomas Gloy, Im Dienst der Gemeinschaft: Zur Ordnung der Moral in der Hitler-Jugend. Göttingen 2018.

- ↑ See, e.g., the collection of the Lebendiges Museum Online (LeMO) on youth under Nazism: https://www.dhm.de/fileadmin/lemo/suche/search/index.php?q=seitentyp:Zeitzeuge&f[]= epoche:NS-Regime.

- ↑ See Ernst Berger (ed.), Verfolgte Kindheit: Kinder und Jugendliche als Opfer der NS-Sozialverwaltung, Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2007. On Swing Youth, see Alenka Barber-Kersovan/Gordon Uhlmann (eds), Getanzte Freiheit: Swingkultur zwischen NS-Diktatur und Gegenwart, Hamburg 2002.

- ↑ On the concept of “total institutions,” see Erving Goffman, Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates, Garden City, NY, 1961.

- ↑ John S. Wilson, Scouting Round the World, London 1959.

- ↑ See Freie Deutsche Jugend, Dokumente zur Geschichte der Freien Deutschen Jugend, 4 vols., Berlin (East) 1960-1963; Karl Heinz Jahnke et al., Geschichte der Freien Deutschen Jugend, Berlin (East) 1976. A West German perspective is offered by Arnold Freiburg/Christa Mahrad, FDJ: Der sozialistische Jugendverband der DDR, Opladen 1982.

- ↑ Matthias Judt (ed.), DDR-Geschichte in Dokumenten. Beschlüsse, Berichte, interne Materialien und Alltagszeugnisse, Berlin 1998, pp. 54f; Ulrich Mählert/Gerd-Rüdiger Stephan, Blaue Hemden, Rote Fahnen: Die Geschichte der Freien Deutschen Jugend, Opladen 1996, pp. 44-49.

- ↑ Cited in Wolfgang R. Krabbe, Parteijugend in Deutschland: Junge Union, Jungsozialisten und Jungdemokraten, 1945-1980, Wiesbaden 2002, p. 12. On the history of party youth in the Federal Republic, see also Martin Oberpriller, Jungsozialisten: Parteijugend zwischen Anpassung und Opposition, Bonn 2004; Claus-Peter Grotz, Die Junge Union: Struktur, Funktion, Entwicklung der Jugendorganisation von CDU und CSU seit 1969, Kehl et al. 1983; for the United States, see the entries on “Young Democrats of America” and “Young Republican Club” in: Larry J. Sabato/Howard R. Ernst (eds.), Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections, New York 2006, pp. 496-497. On trade-union youth groups, see Knud Andresen, Gebremste Radikalisierung: Die IG Metall und ihre Jugend 1968 bis in die 1980er Jahre, Göttingen 2016.

- ↑ Dietmar Süß, “Die Enkel auf den Barrikaden: Jungsozialisten in der SPD in den Siebzigerjahren,” in: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 44 (2004), pp. 67-104, esp. p. 71.

- ↑ See Macleod, Building Character; Martin Kalb, Coming of Age: Constructing and Controlling Youth in Munich, 1942-1973, New York 2016. For a Soviet perspective, see Anne E. Gorsuch, Youth in Revolutionary Russia: Enthusiasts, Bohemians, Delinquents, Bloomington, IN, 2000.

- ↑ See, e.g., Uta G. Poiger, Jazz, Rock and Rebels: Cold War Politics and American Culture in a Divided Germany, Berkeley/Los Angeles 2000; Leerom Medovoi, Rebels: Youth and the Cold War Origins of Identity, Durham, NC, 2005; Leonard Schmieding, Das ist unsere Party: HipHop in der DDR, Stuttgart 2014; Bodo Mrozek, Jugend – Pop – Kultur: Eine transnationale Geschichte, Frankfurt am Main 2019.

- ↑ For an introduction, see Stanley Cohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics, London 1972.

- ↑ See, among others, Mark Fenemore, Sex, Thugs, and Rock’n’Roll: Teenage Rebels in Cold War East Germany, New York 2007, p. 177.

- ↑ Michael Rosenthal, The Character Factory: Baden-Powell and the Origins of the Boy Scout Movement, New York 1986.

- ↑ See Karl Braun/John Khairi-Taraki/Felix Linzner (eds.), Avantgarden der Biopolitik: Jugendbewegung, Lebensreform und Strategien biologischer „Aufrüstung”, Göttingen 2017.

- ↑ Representative for this changing perception are James Marten (ed.), Children and War: A Historical Anthology, New York 2002; Nicholas Stargardt, Witnesses of War: Children’s Lives Under the Nazis, London 2005; Manon Pignot, Allons enfants de la patrie: Génération Grande Guerre, Paris 2012; Mischa Honeck/James Marten (eds.), War and Childhood in the Era of the Two World Wars, New York 2019 (forthcoming).

- ↑ Sabine Frühstück, Playing War: Children and the Paradoxes of Modern Militarism in Japan, Berkeley, CA, 2017.

- ↑ See, e.g., Tracy C. Davis, Stages of Emergency: Cold War Nuclear Civil Defense, Durham/London 2007, pp. 25-28.

- ↑ For an epoch-spanning study, see Alexander Denzler/Stefan Grüner/Markus Raasch (eds.), Kinder und Krieg: Von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart, Berlin 2016.

- ↑ See George L. Mosse, The Image of Man: The Creation of Modern Masculinity, New York 1996; Birgit Dahlke, Jünglinge der Moderne: Jugendkult und Männlichkeit in der Literatur im 1900, Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2000.

- ↑ On Theodore Roosevelt, see idem, The Strenuous Life: Essays and Addresses, New York 1906, S. 3-22.

- ↑ Robert H. MacDonald, Sons of the Empire: The Frontier and the Boy Scout Movement, 1890-1910, Toronto 1993; Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917, Chicago 1995; Clifford Putney, Muscular Christianity: Manhood and Sports in Protestant America, 1880-1920, Cambridge, MA, 2001. A similar causal relationship in the German Wandervogel movement is established by Claudia Bruns, Die Politik des Eros: Der Männerbund in Wissenschaft, Politik und Jugendkultur (1880-1934), Cologne/Weimar/Vienna 2008.

- ↑ See Dahlke, Jünglinge der Moderne; Marilyn Lake/Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men’s Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality, New York 2008; Jürgen Martschukat/Olaf Stieglitz (eds.), Väter, Soldaten, Liebhaber: Männer und Männlichkeiten in der Geschichte Nordamerikas – Ein Reader, Bielefeld 2007. On the concept of hegemonic masculinity, see R.W. Connell/James W. Messerschmidt, “Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept,” in: Gender & Society 19 (2005), no. 6, pp. 829-859.

- ↑ Cited in Hermann Weber (ed.), Lenin: Aus den Schriften, 1895-1923, Munich 1980, p. 123.

- ↑ See, e.g., Benjamin René Jordan, Modern Manhood and the Boy Scouts of America: Citizenship, Race, and the Environment, 1910-1930, Chapel Hill, NC, 2016; Matthias Neumann, The Communist Youth League and the Transformation of the Soviet Union, 1917-1932, London 2011.

- ↑ On the popularity of playing Indians in various organizations, see Deloria, Playing Indian, pp. 95-127; Paul C. Mishler, Raising Reds: The Young Pioneers, Radical Summer Camps, and Communist Political Culture in the United States, New York 1999, pp. 83-108; Frank Usbeck, Fellow Tribesmen: The Image of Native Americans, National Identity, and Nazi Ideology in Germany, New York 2015, pp. 95-97.

- ↑ Two fundamental works are Gabriele Winker/Nina Degele, Intersektionalität: Zur Analyse sozialer Ungleichheiten, Bielefeld 2009; Patrick R. Grzanka, Intersectionality: A Foundations and Frontiers Reader, Boulder, CO, 2014.

- ↑ On the League of German Girls, see Birgit Jürgens, Zur Geschichte des BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädel) von 1923 bis 1939, Frankfurt am Main 1996; Sabine Hering/Kurt Schilde, Das BDM-Werk „Glaube und Schönheit“: Die Organisation junger Frauen im Nationalsozialismus, Wiesbaden 2004.

- ↑ See Mishler, Raising Reds; Gorsuch, Youth in Revolutionary Russia; Neumann, The Communist Youth League.

- ↑ On the origins of the Girl Guides and Girl Scouts and other early girls’ organizations, see Susan A. Miller, Growing Girls: The Natural Origins of Girls’ Organizations in America, New Brunswick, NJ, 2007; Tammy M. Proctor, Scouting for Girls: A Century of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts, Santa Barbara, CA, 2009. On developments in Germany, see Christiane Kliemannel, Mädchen und Frauen in der deutschen Jugendbewegung im Spiegel der historischen Forschung, Rudolstadt 2010.

- ↑ Jeal, Baden-Powell, pp. 469-471.

- ↑ See Dagmar Herzog, Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany, Princeton 2005, pp. 10-63; Sam Pryke, “The Control of Sexuality in the Early British Boy Scouts Movement,” in: Sex Education 5 (2005), no. 1, pp. 15-28; Gabriel N. Rosenberg, The 4-H Harvest: Sexuality and the State in Rural America, Philadelphia 2015.

- ↑ Kirk Johnson, “Boy Scout Files for First Time Give Glimpse into 20 Years of Sex Abuse,” in: New York Times, October 18, 2012, online at https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/19/us/boy-scout-documents-reveal-decades-of-sexual-abuse.html. See also Christian Füller, “Missbrauch, Gewalt, Ideologie: Wie Ideen sexuelle Gewalt ermöglichen,” in: Wilfried Breyvogel (ed.), Pfadfinderische Beziehungsformen und Interaktionsstile: Vom Scoutismus über die bündische Zeit bis zur Missbrauchsdebatte, Wiesbaden 2017, pp. 237-251. For a journalistic work on the topic, see Patrick Boyle, Scout’s Honor: Sexual Abuse in America’s Most Trusted Institution, San Francisco 1994.

- ↑ A balanced portrayal of youth and sexuality under Nazism is offered by Elizabeth D. Heinemann, “Sexuality and Nazism: The Doubly Unspeakable?” in: Dagmar Herzog (ed.), Sexuality and German Fascism, New York 2005, pp. 29-33.

- ↑ See Susan Whitney, Mobilizing Youth: Communists and Catholics in Interwar France, Durham, NC, 2009, p. 51; Neumann, The Communist Youth League, pp. 147-149; Leonore Ansorg, Kinder im Klassenkampf, Die Geschichte der Pionierorganisation von 1948 bis Ende der fünfziger Jahre, Berlin 1997, pp. 16-17, 90.

- ↑ See Tammy M. Proctor, On My Honor: Guides and Scouts in Interwar Britain, Philadelphia 2002, pp. 131-154; Mischa Honeck, Our Frontier Is the World: The Boy Scouts in the Age of American Ascendancy, Ithaca, NY, 2018, pp. 103-104.

- ↑ See Alessio Ponzio, Shaping the New Man: Youth Training Regimes in Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Madison, WI, 2015; as well as the dissertation of Timo Holste, Contested Internationalism: Das Boy Scouts International Bureau und der Aufstieg des Faschismus, 1930-1946, Universität Heidelberg 2018.

- ↑ Christina Norwig, Die erste europäische Generation: Europakonstruktionen in der Europäischen Jugendkampagne, 1951-1958, Göttingen 2017. On the history of youth volunteer service in Western Europe, see Christine G. Krüger, Dienstethos, Abenteuerlust, Bürgerpflicht: Jugendfreiwilligendienste in Deutschland und Großbritannien im 20. Jahrhundert, Göttingen 2016.

- ↑ See Georg Jäschke, Wegbereiter der deutsch-polnisch-tschechischen Versöhnung? Die katholische Vertriebenenjugend 1946-1990 in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Münster 2018.

- ↑ On the history of Jewish and Jewish-Zionist youth organizations, see Christian Faust, “Der Blau-Weiß-Zionismus und das Geschlechterverständnis in der frühen jüdischen Jugendbewegung,” in: Sabine Haustein/Victoria Hegner (eds.), Stadt, Religion, Geschlecht: Historisch-ethnografische Erkundungen zu Judentum und neuen religiösen Bewegungen in Berlin, Berlin 2010, pp. 124-144; Ulrike Pilarczyk et al., Gemeinschaft in Bildern: Jüdische Jugendbewegung und zionistische Erziehungspraxis in Deutschland und Palästina/Israel, Göttingen 2009.

- ↑ Mishler, Raising Reds, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ Wilson, Scouting Round the World, pp. 79, 81.

- ↑ The latter is indicated in the diary entries of American Boy Scouts who took part in international jamborees in Europe between the wars. See Honeck, Our Frontier Is the World, pp. 97, 124.

- ↑ See Pierre Brocheux, Ho Chi Minh: A Biography, New York 2007, p. 96.

- ↑ Kristin Mulready-Stone, Mobilizing Shanghai Youth: CCP Internationalism, GMD Nationalism and Japanese Collaboration, New York 2015, ch. 6.

- ↑ Siehe Timothy Parsons, Race, Resistance, and the Boy Scout Movement in British Colonial Africa, Athens, OH, 2005, S. 195.

- ↑ Honeck, Our Frontier Is the World, pp. 88-128; Margaret Peacock, Innocent Weapons: The Soviet and American Politics of Childhood in the Cold War, Chapel Hill 2014, pp. 114-116.

- ↑ On segregation, see Jordan, Modern Manhood, pp. 194-213; on decolonization, see Parsons, Race, Resistance, and the Boy Scout Movement, pp. 240-241.

- ↑ See Denise Wesenberg, “Die X. Weltfestspiele der Jugend und Studenten 1973 in Ost-Berlin im Kontext der Systemkonkurrenz,” in: Michael Lemke (ed.), Konfrontation und Wettbewerb. Wissenschaft, Technik und Kultur im geteilten Berliner Alltag (1948-1973), Berlin 2008, pp. 333-352; Andreas Ruhl, Stalin-Kult und Rotes Woodstock. Die Weltjugendfestspiele 1951 und 1973 in Ostberlin, Marburg 2009; Kay Schiller, “Communism, Youth and Sport: The 1973 World Youth Festival in East Berlin,” in: Alan Tomlinson/Christopher Young/Richard Holt (eds.), Sport and the Transformation of Modern Europe. States, Media and Markets, 1950–2010, London 2010, pp. 50-66. On the broader context, see also Quinn Slobodian (ed.), Comrades of Color: East Germany in the Cold War World, New York 2015; and the dissertation of Nick Rutter, Enacting Communism: The World Youth Festival, 1945-1975, Yale University 2013.

- ↑ See esp. Wesenberg, “Die X. Weltfestspiele.”

- ↑ Liisa Malkki, “Children, Humanity, and the Infantilization of Peace,” in: Ilana Feldman/Miriam Ticktin (eds.), In the Name of Humanity: The Government of Threat and Care, Durham, NC, 2010, pp. 58-85, here p. 60.

- ↑ Richard Ivan Jobs, Backpack Ambassadors: How Youth Travel Integrated Europe, Chicago 2017.

- ↑ Jobs/Pomfret, “The Transnationality of Youth,” pp. 1-19.

- ↑ Owen Matthews, “How Can American Stay Out of War?” in: Boys’ Life (July 1936), pp. 19, 49; see also Honeck, Our Frontier Is the World, pp. 116-128.

- ↑ Nick Rutter, “Unity and Conflict in the Socialist Scramble for Africa, 1960-1970,” in: Tamara Chaplin/Jadwiga E. Pieper Mooney (eds.), The Global 1960s: Convention, Contest, and Counterculture, New York 2018, pp. 34-52, esp. p. 43.

- ↑ Honeck, Our Frontier Is the World, pp 104, 115.

- ↑ Kristine Alexander, Guiding Modern Girls: Girlhood, Empire, and Internationalism in the 1920s and 1930s, Vancouver 2017, pp. 43, 135-136.

- ↑ Roland Robertson, Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture, London 1992; idem., “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity,” in: Mike Featherstone/Scott Lash/Robert Robertson (ed.), Global Modernities, London 1995, pp. 25-44.

- ↑ Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, New York 2000, esp. pp. 277-286.

- ↑ See David Templin, Freizeit ohne Kontrollen: Die Jugendzentrumsbewegung in der Bundesrepublik der 1970er Jahre, Göttingen 2015.

- ↑ This theory is put forth by Karin Priester, Warum Europäer in den Heiligen Krieg ziehen: Der Dschihadismus als rechtsradikale Jugendbewegung, Frankfurt am Main/New York 2017.