Historical comparison has changed considerably over the past forty years,[1] both in terms of its status within historical studies and its application in research practice, the fields and periods of comparison, the topics of historical comparison, and the methods and impetuses from other academic disciplines. This article begins with definitions of historical comparison, then outlines the debates on historical comparison and thereafter deals with the changes in historical comparison over the past decades.

1. What is Historical Comparison?

In the early days, historical comparison was understood to mean the systematic comparison of two or more historical units (places, regions, nations or civilisations, including historical personalities) in order to explore similarities and differences, convergences and divergences. From the outset, the aim was not only to describe typologies, but also to explain and develop them. Practitioners of such comparisons did not adopt John Stuart Mill’s fundamental separation between the method of difference and the method of correspondence, i.e. the analysis of differences or parallels and similarities; both approaches were included in historical comparisons.[2]

However, for a long time, historical comparison was often put into practice via differences. Major debates among historians about American exceptionalism, the exception française, the special development of Great Britain, the peculiarities of the Japanese economy or the German Sonderweg centred entirely on differences. Sometimes, observers have even concluded that historical comparison is by its very nature centred on differences. Recent developments, however, have shifted the emphasis away from differences and towards similarities. The interest in global history, as well as the intra-European comparison in the course of Europeanisation, have contributed to this. The two major books on the global history of the long 19th century – by Jürgen Osterhammel and Christopher A. Bayly – are impressive examples of the comparative search for both differences and similarities. The latest volumes on Franco-German history, for example, are far less focused on national differences than the research of thirty years ago. Even in the numerous syntheses on European history, historians tend to concentrate on European similarities alongside intra-European differences at the national and regional levels.[3]

Historical comparison is not uniform and includes a wide variety of approaches. Historical comparison can be used to analyse cases from the same epoch, as well as from different historical periods. It can be used to compare international spaces, or regions, places, families or individuals within a country. Historical comparison can be limited to cases from the same culture, as the old master of historical comparison Marc Bloch demanded, but it can also juxtapose cases from completely different civilisations, as in the debate about the rise of Europe and the lagging development of China in the 18th and 19th centuries.[4] Comparative cases can be examined with equal intensity, or one case can be placed at the centre in an asymmetrical comparison, while historians can only take brief comparative glances at other cases. Historical comparison can only deal with two cases or a larger number of cases, although this is usually limited by the fact that historians endeavour to place each comparative case in its historical context. When embarking on a comparative historical project, it is important to realise the diversity of options.

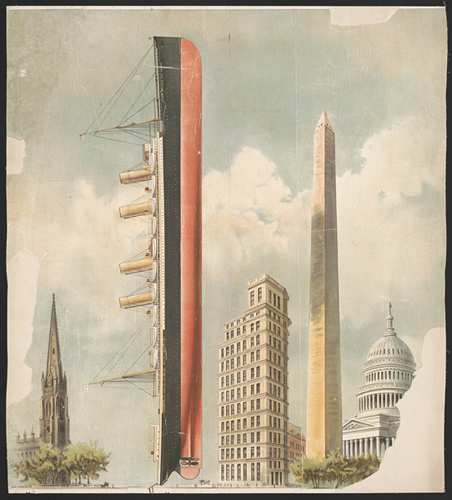

Alexander von Humboldt: Die geographische Verbreitung der Pflanzen. Grundzüge der Botanischen Geographie: Die Verteilung der Pflanzen in senkrechter Richtung, in: The Physical Atlas, A Series of Maps & Illustrations of the Geographical Distribution of Natural Phenomena. Johnston, Alexander Keith, 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Alexander_von_Humboldt_-_1850_-_Geographical_Distribution_of_Plants.jpg [06.11.2024], public domain

There have been attempts to typologise differences between historical comparisons. The intentions of historical comparisons can be categorised into three types: analytical comparison, which helps to develop explanations for a historical phenomenon through the comparative analysis of different cases; contrastive, enlightening comparison, which can deal with the development of democracy or human rights, for example, and contrasts their historical implementation in some countries with their historical failure in other countries; understanding and simultaneously distancing comparison, through which other countries are better understood in historical comparison with the historian’s own country; at the same time, this method can facilitate a different perspective on the historical self-understanding of one’s own country, which can lead to revisions of such self-concepts.[5]

Another typology is based on the fundamental contrast between the individualising comparison, which focuses on the individual case and is pursued by most historians, and the generalising comparison, which is concerned with general developments. The social scientist Charles Tilly distinguished four types of comparison in his now classic, oft-cited typology: the individualising comparison, which works out the particularities of two or fewer cases; the inclusive comparison, which compares parts of a larger whole, such as the colonies of an empire; the variation comparison, which concentrates on the variants of a general universal process, such as urbanisation or demographic transition; and finally the generalising comparison, which is concerned with identifying general rules.[6]

The classical definition of historical comparison was in need of supplementation and has been amended in various ways. Three particularly important openings should be mentioned here.

First, there has been intensive discussion in recent years about opening up historical comparison to include the history of relationships between case studies, i.e. a closer look at transnational transfers, international interdependencies, images of the own and the other. Today, the relationships between the comparative cases analysed are generally included in the definition of comparison. The mere confrontation of the cases appears to have become too narrow, as will be discussed later.

Second, one long-existing, yet hardly discussed, application of historical comparison is to the comparison between successive epochs of a territorial unit. Historians often apply this mode of historical comparison, but they do not usually refer to it as a comparison. At first glance, the difference to comparison seems difficult to comprehend, because it involves similar methods of analysis to historical comparison. What is explored as upheavals between epochs, for example, bears a strong resemblance to the identification of differences between comparative cases; similarly, what historians see as continuity between epochs is very similar to the apperception of similarities between comparative cases.

Nevertheless, historians do not count such inter-epochal comparisons as historical comparisons because historical development on the time axis has a fundamentally different character than the juxtaposition of two spatially and perhaps also temporally separate cases. Historical development creates a dense relationship of causalities, experiences and memories between successive epochs within the same country or the same place, which is inconceivable when comparing different places or countries of the same epoch. Nevertheless, the boundaries for comparison are fluid. Comparisons between instances of the same continent, country or place that are far apart in time, such as between the French Revolution of 1789 and the Russian Revolution of 1917, or between Charles V and Napoleon I, or between Paris in the Roman Empire and Paris in the Second Empire, tend to be regarded as historical comparisons. The question of what makes a comparison between epochs different from a historical comparison, leads to interesting new considerations.

A third method that is also rarely discussed yet often used by historians is the historical depiction of international developments, which deals with many countries that are often very different in character. With the growing interest in global history and in the history of Europe, historians have applied this mode of historial comparison more frequently, both in the form of syntheses and in the form of monographs on international processes, institutions or ideas. Such studies are usually not comparative in the strict sense, because they are primarily concerned with common trends, and they usually address differences in an unsystematic way, in a synthesis of European history or Latin American or African or Southeast Asian history, as well as in global studies of civil rights or women's movements or educational opportunities, to name just a few topics. It is not possible to compare the multitude of countries in the same depth as two individual countries in a binational comparison. But even in such syntheses and analyses, historians make comparisons, albeit using different methods and with a different proximity to the sources. Ultimately, they are also part of historical comparison.

2. Debates about Historical Comparison

Since the 1990s, a whole series of debates have ignited around the classical historical comparison, especially between French, American and German comparative historians and literature specialists. These methodological debates, which were not always encouraging for younger historians, have since died down again, but today's historical comparison is difficult to understand without these productive debates, which we will review here in abbreviated form. These debates did not simply follow research practice; they sometimes preceded it, and they sometimes lagged behind it.

In the 1990s, the French literature specialist Michel Espagne, an expert on Franco-German relations, criticised historical comparison because it forced researchers to construct artificially homogeneous national units, thereby not only overlooking the diversity within each country, but also taking us back to the age of the often detrimental attachment of historical studies to national identities. Furthermore, according to Michel Espagne, historical comparison can only be used for structural analyses and ignores the experiences and actions of the individual. He therefore argued in favour of replacing historical comparison with historical transfer studies, i.e. the study of the transfer of ideas and values, the exchange of goods and the migration of people from one society to another, which would open up historical studies to international cultural interdependencies and the cultural history of experiences and practices.[7] Espagne was not the only scholar to lodge this critique.

Another objection to historical comparison came from global historians. They argued that the historical comparison with non-European countries over-emphasised the superiority of Europe, especially the Europeanisation of the non-European world, and the backwardness of non-European regions since the late 18th century. This neglects the notion of ‘shared history’ or ‘entangled history’, i.e. the influence of the non-European world on Europe not only indirectly through the non-European experiences of Europeans, but also directly through intercontinental transfers of non-European goods, plants, music, humanities and technological knowledge to Europe. Some global historians therefore also place such transfers at the centre of their studies. Others want to focus entirely on global institutions, movements, public spheres, conflicts and upheavals. They are less interested in units smaller than the world as a whole, and are thus hardly interested in historical comparisons.[8] For Sebastian Conrad, a leading global historian, however, comparative history provides important inspiration.[9]

A third challenge for historical comparison arose from transnational history, which gained momentum in the 2000s and early 2010s. This field was primarily understood as a departure from purely national history and as an internationalisation of research topics, without a single sophisticated concept or even a theory behind it. Impulses for transnational history came from very different directions: particularly clearly from global history;[10] from diplomatic history, which is more interested in the broad social and cultural context of international relations; from non-European history, which broke away from the concept of regional studies and sought to work more closely with historians from other regions of the world; from post-colonial history; from social and cultural history, which became more internationalised; from historians of European integration, who wanted to expand the purely political history of decision-making.

What was decisive for historical comparison here was that in the new programmatic texts on transnational history, historical comparison was usually not attacked at all; on the contrary, it was mostly ignored, as in the case of Akira Iriye and Pierre-Yves Saunier, who by transnational history primarily mean interrelationships and transfers of ideas, people and goods across national borders.[11] Only gradually did a connection emerge between historical comparison and transnational history.[12] The historian Margrit Pernau saw in her synthesis of transnational history an approach towards a changed historical comparison.[13]

The concept of ‘histoire croisée’ (crossed history) by Michael Werner and Bénédicte Zimmermann offered a synthesis of these debates. On the one hand, they recognised historical comparison as an indispensable method of historical scholarship, but on the other hand they called for a fundamental change in historical comparison as well as in transfer research: for continuous reflection on and empathy with the other compared culture, and constant examination of the image of one's own culture, as early as in the formulation of questions and research design.[14]

The impact of these debates on research practice should not be overestimated. They were conducted in publications between a small number of historians. However, these historians were almost always not pure methodological theorists, but usually made comparisons themselves. These debates were therefore read by other comparative historians, had an impact on the practice of historical comparison, or at least reflected the changes in historical comparison.

3. Changes in Comparison

Classical historical comparison changed in six dimensions. First, it became normal. Second, it changed methodologically and included transnational exchange in the comparison. Third, it expanded thematically and was applied in all subject areas of historical studies, no longer primarily in specific fields. Fourth, its geography expanded. Fifth, it opened up new time periods: The period after 1945 became a new Eldorado of historical comparison, a period in which the nation state looked fundamentally different than before 1914 or in the interwar period. Sixth, the connection to fundamental theorems changed. The significance of neighbouring sciences, from which many ideas for comparison were taken, shifted.

The first change can be described as normalisation. The classical historical comparison of the 1970s and 1980s possessed a relatively high level of prestige in historical studies, and was even described as the ‘royal road’. Historical comparison had long roots not only in historical sociology, above all Max Weber, but also in historians such as Marc Bloch, Henri Pirenne, Otto Hintze and, in some cases, Karl Lamprecht.[15] Comparativists sometimes saw themselves as pioneers of an international opening of historical studies, which could be thematically much more comprehensive and diverse than the history of diplomacy or the international history of ideas. But historical comparison was only practised by a small group, with only a few comparisons being published each year. Historical comparison was considered risky for dissertations and post-doctoral theses.

In recent decades, historical comparison has moved on from this marginalised position. It has become a normal method used by historians in a discipline in which more methods are practised than in the 1970s. Historical comparison lost its pioneering character, including the glamour of the new, as more and more historians began working from a comparative perspective. The writing of comparative dissertations and post-doctoral theses was no longer a rare event. Historical comparisons continued to increase, particularly in Germany and France, right up to the present day. In the USA, their number remained at least at a stable level; today, historical comparisons can draw on a broad pool of several hundred historical studies without anyone really having counted them. Normalisation also means that this development was not linear. After an initial upswing in the 1970s and 1980s, the number stopped increasing in the 1990s and 2000s against the backdrop of the aforementioned debates and even decreased. Only since the end of the 2000s has the number of comparisons practised in the new contexts increased again.[16]

This growth in comparative work did not occur in a vacuum. Historians who chose this method encountered increasingly favourable financial conditions, as historical comparison was promoted by international research centers and conferences, institutes abroad, international networks, and foundations such as the European Research Council. These circumstances coincided with the recognition that comparative publications improved career opportunities, as one's own expertise extended to several countries and thus made it possible to apply for different chairs. The method of historical comparison also reflected the internationalisation of everyday life in Europe through travel, international educational and working stays, migration and the numerous private and international connections that arose as a result.

Historical comparison was not just a passing fashion. It became an established method in historical studies because the society in which historians today work thinks intensively in terms of comparisons. In the increasingly intensive personal encounters and experiences with other European and non-European cultures, comparisons are constantly being made and judgements passed. In this encounter and dialogue with others, assistance or critique from comparative historians is often helpful. The use of international comparison is not new in politics; it has been on the rise since the 1990s in the European Union with the open method of coordination and in international organisations, for example with the regular PISA studies of the OECD since 2000, as well as in countless international rankings of countries, cities, companies, scholars and artists.[17] To abandon historical comparisons would therefore mean no longer facing up to an important responsibility of historical scholarship.

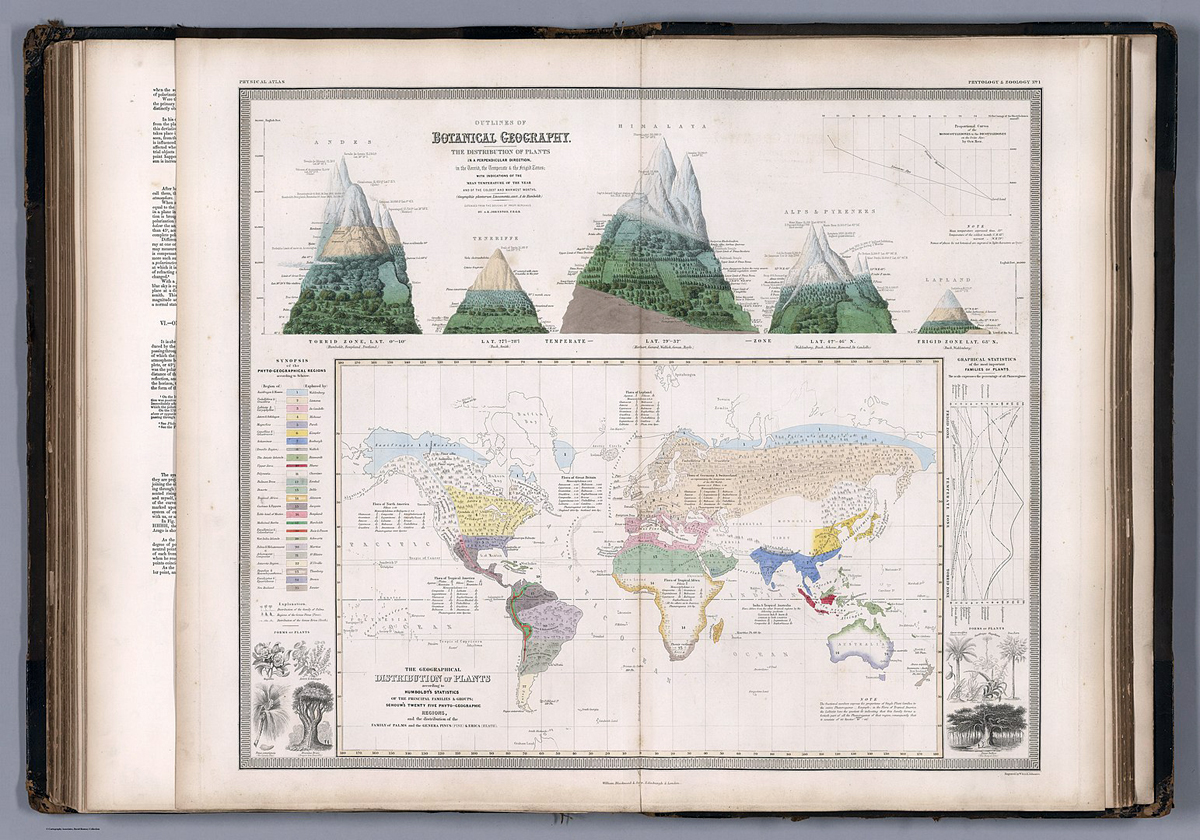

Comparative chart: “Women in political office 2020, in percent”. Source: ILO/Heinrich Böll Foundation/Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frauen_in_politischen_%C3%84mtern_(50718474193).png [06.11.2024], license: CC BY-SA 2.0 Deed https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.de

However, this normalisation of historical comparison, as well as the effect of the aforementioned debates, has led historians to become more aware of the problems of comparison: the danger of bias in national ways of thinking and mere self-affirmation through historical comparison; the overstatement of the developments that prevailed in the end and the understatement of the alternatives that remained weak; the neglect of the internal diversity of the comparative cases that complicated the comparison; the dependence of the selection of comparative cases on available sources and on the language skills of the comparative historian; the often unspoken assumptions about the normality or even superiority of one of the comparative cases, sometimes of one's own country, sometimes of other countries.

The second change in historical comparison is a methodological expansion: the opening of the comparison to the history of relationships between the compared cases, i.e. to transfers, to interdependencies, and to images of the self and the other. This broadening of the approach has become widely accepted because historians have recently not been content in general with the juxtaposition of individual cases in historical comparisons. They are also more often interested in the influence the compared cases had on each other, how strongly they were intertwined, and how contemporaries perceived the differences or similarities between the cases being compared. Whether a transnational historical study emphasises comparisons or transfers, interdependencies or reciprocal images, or whether it treats all these approaches equally, depends above all on the research question, the characteristics of the chosen comparison, the sources available for the respective project, and the intellectual currents that prevail at the time. This methodological expansion has improved the comparison.

However, there were also disappointments. The inclusion of the history of relationships in the practice of comparison led to new experiences. Transfers, interdependencies and images ‘of the other’ are not equally dense and comprehensible everywhere; sometimes, such evidence is disappointingly thin. Even between neighbouring and closely intertwined countries such as France and Germany, transfers between political or cultural public spheres have decreased in some cases since 1945. There is even talk of the paradox of declining transfers between countries that are close intertwined both economically and politically.[18]

Moreover, in the early days, it was primarily countries that were politically and culturally on an equal footing with each other for which the demand for more relationship history was realised in historical comparisons. Relations between France and Germany were often the inspiration for these demands. However, equality is not the rule. Historical comparisons are often made between countries that are positioned very differently in the international hierarchy or are even dependent on each other. This applies not only to comparisons between the northern and southern hemispheres, but often also to historical comparisons within Europe. Transfers to lower-positioned or dominated societies tend to be overestimated, while transfers to better-positioned or dominant societies tend to be underestimated. Therefore, including transfers in the comparison also means analysing transfers between unequally positioned countries more closely.

Finally, the inclusion of the history of relations in the historical comparison between many cases looks fundamentally different from the usual historical comparison between two or three cases. These comparisons between several cases have been neglected thus far. Transfers between many countries often become hybrid transfers in which the contributions of individual countries are difficult to recognise and which therefore need to be examined differently. Interdependencies between many countries could look very different. They range from ‘spider webs’ in which one country or one actor played a central role, to interlinkages in which each country has an equal weight. Even in the case of interdependencies, untested assumptions can lead to dead ends. Reciprocal images cannot be analysed for all pairs of countries in comparisons with many countries. Taking up a history of relations in historical comparison therefore often requires different research designs.[19]

However, this expansion of historical comparison was also facilitated by the fact that the undeniable methodological problems that historians have to deal with when using the method of historical comparison often exist in the history of relationships as well. For transfer and entanglement studies, too, the units between which transfers or entanglements exist must be constructed or contemporary constructions must be sought out – and are then perhaps overestimated. Moreover, just like historical comparison, transfer studies have a dark history. They could also be used as a component of ‘enemy sciences’: for example, “Westforschung” (research on the West) during the period of Nazi rule about alleged Germanic transfers to northern Belgium and France, the thesis of the older European colonial sciences of the primarily beneficial Europeanisation of the colonial populations, or some of the theses developed during the Cold War about the complete Sovietisation of Eastern Central Europe.[20]

The third change in historical comparison is the greater diversity of topics. The classical comparison focussed on a few fields of historical studies, on social and economic history, as in the case of Germany or the USA, and on cultural history, as in the case of France. Thematically, the use of comparison was concentrated in a few subject areas such as the welfare state, family, workers, the middle class, social protests and revolutions, industrialisation and enterprises. This changed. Historical comparison was increasingly used in all subject areas of historical research, no longer just in specific fields: in structural history as well as in the history of experience and ideas, in cultural and political history as well as in social and economic history.

In addition to comparisons between two or just a few countries, international synthesis with numerous comparisons in many subject areas has increased, in the history of capitalism and in the history of social inequality, in the history of civil rights and in the history of intellectuals, in the history of empires and colonies and in environmental history, in the history of opera and theatre as well as in the history of women and gender, to name just a few subject areas. Thematically, there were no longer any recognisable barriers to comparison.

The fourth change was the expansion of the areas of comparison and gradual disengagement from a Eurocentric focus. The area of classical historical comparison was Europe, sometimes also the West, including the USA, as the benchmark of modernity. In Europe, the comparison largely focussed on France, Great Britain and Germany, with occasional glances at Sweden or Switzerland as particularly modern countries, or at Italy and Eastern Europe as less modern parts of the continent. Comparisons with non-European countries were rarely made. However, French research was a significant exception. In France, historical comparison was initially driven primarily by experts from non-European countries. For this reason, non-European countries were initially included in comparisons more frequently than elsewhere. Unlike in Germany or the USA, comparisons were not necessarily made with the author’s own country, i.e. France.[21]

In recent decades, the Europe-centred nature of comparison has weakened somewhat. The comparison with non-European countries beyond the USA, on the other hand, increased, especially the comparison with East Asia.[22] The changed global political situation, the end of the Cold War, and the emergence of a world with several centres of power, also began to have an impact on historical comparison. European experts of non-European countries now played an important role in the gradual global opening of historical comparison, and not only in France. At the same time, scholars in France also turned more towards Europe and compared their own country with other, mostly European countries.[23] On the whole, however, European historical comparison remained and remains strongly focussed on Europe. Comparisons with the neighbouring Arab and African world are still just as rare as with other, more distant regions of the world, such as Latin America, South Asia or Southeast Asia.

A fifth change concerns the connection to theories. The most important, if not the only, theoretical link to classical historical comparison was modernisation theories, but not in a simple sense. Historical comparison did not simply mean classifying the compared cases into different degrees of modernisation; it also meant working out different paths of modernisation or pointing out contradictions between political and economic modernisation. The attraction of using historical comparison as a method in research usually lay not simply in the proof of modernisation, but also in the discussion of the obstacles and contradictions of historical development in relation to modernisation theories. In this sense, industrialisation, enterprises, literacy, family and demographic transition, social classes, social conflicts and revolutions, education systems, welfare states, urban planning, political parties and constitutions were compared.

In recent decades, however, the modernisation paradigm of both non-Marxist and Marxist origin has lost some of its influence on historical comparison. Historical comparison no longer merely served to classify modernising developments; it also facilitated a better understanding of the other and often also the self. More often, comparison meant wanting to understand the other better and no longer just pursuing the realisation of modernity. For this better understanding of the other, the precise comparison between the self and the other helped. Not only does it make it possible to show more precisely how the self differed from the other, where transfers and interdependencies were dense or were fended off, but in addition to reflections on one's own unexpected and overlooked similarities, convergences and interdependencies can also be revealed.

In this context, the seventh change, which arose due to impulses from other disciplines, can be identified. For the classical, still rather rare, historical comparison, particularly important impulses came from American historical social scientists such as Charles Tilly, Karl Deutsch, Reinhard Bendix and Barrington Moore, but also from European historical social scientists such as Stein Rokkan and Peter Flora.[24] The early comparative historians were often in direct personal contact with these scholars. This gradually changed.[25] Relationships with American comparative social science remained important, but American research lost its reference character for European historical comparison, since comparison became strongly established in Europe and political science in Europe became a discipline with particularly intensive comparative research, even more so than sociology. However, this gave rise to other interdisciplinary relationships. In the presentation of these comparative studies in political science textbooks, historical comparison has only played a minor role in recent times. Interdisciplinary links with historians were therefore rather rare. At the same time, a whole series of political scientists, such as Peter Katzenstein, Maurizio Cotta, Bertrand Badie, Ivan Krastev, Stephan Leibfried, Wolfgang Merkel and Herfried Münkler, to name just seven leading names, have made significant historical comparisons that have had an impact on historical studies; however, they have rarely written about the methodology of historical comparison.[26]

4. Summary

All in all, historical comparison today is not an obsolete, earlier stage of international history, one that contained too much national history and that was subsumed first by transfer studies and then by transnational history, as some have posited in exaggerated fashion. Over the past forty years, historical comparison has established itself as a mature method of historical studies that increasingly finds both regular and frequent expression, building on significant predecessors among historians and social scientists in the first half of the 20th century.

At the same time, historical comparison has changed considerably in recent decades. Its application has become routinised and standardised in research practice. In the process, its pioneering aura and with it the glamour of the new has been lost, but this has led to it being used in a more self-critical and reflective way. Since its establishment as a historical method, it has often been combined with other approaches such as the study of transfer, the study of entanglements or the study of historical representations of the self and the other, yet it is not simply absorbed into these other approaches. It has somewhat expanded its areas of comparison and is somewhat less centred on Europe than before. Its application has been extended to many topics and is now present in all historical topics. Comparativists have turned more strongly to contemporary history since 1945, which in turn has also changed the method, because this epoch leads to other focal points than the former Eldorado of historical comparison, the long 19th century. The method of historical comparison has loosened its originally close ties to the American historical social sciences and modernisation theories and is no longer exclusively an instrument for classification in modernity, but has also become a method for a more precise understanding of the other.

Historical comparison was intensively discussed and criticised, especially in the 1990s and 2000s. It was misunderstood as soon as it was seen exclusively as a rigid construction of national characteristics or even as a breeding ground for national prejudices. There were certainly historical comparisons of this kind, especially in times of international tension and war, when research on other countries was conducted as ‘enemy science’, i.e. as science about the enemy, and often consisted of historical speculation rather than serious research.

Empirically demanding historical comparison, on the other hand, today usually gives historians the opportunity to familiarise themselves intensively with the other country being compared, its historical research, its language and way of thinking, its institutions and norms, and its historical memories. Comparison almost inevitably internationalises the researcher. Today, historical comparison is therefore part of transnational history and thus also part of the liberation of historical science from the corset of pure national history.

However, historical comparison is still strongly focussed on Europe and the West and does not deal enough with Africa, the Arab countries, Latin America, South Asia and Southeast Asia. Within Europe, it concentrates too much on the large countries, on Great Britain, France and Germany. It still compares too many nation states, too few regions and places and at the same time too few world regions.[27] International exchange between comparative historians even seems to be declining recently. Despite changes and improvements to the method, historical comparison is not chiseled in stone. Future generations of historians will continue to adapt it as they see fit.

References

[1] Overviews of historical comparison: Heinz-Gerhard Haupt/Jürgen Kocka (eds.), Geschichte und Vergleich. Ansätze und Ergebnisse international vergleichender Geschichtsschreibung (Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus Verlag, 1996); Marcel Detienne, Comparer l'incomparable, Paris 2000, online at https://archive.org/details/comparerlincompa0000deti [06.11.2024]; Heinz-Gerhard Haupt, “Comparative History,” in: International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001), vol. 4, pp. 2397–2403; Jürgen Kocka, “Comparison and Beyond,” in: History and Theory 42 (2003), pp. 39–44; Heinz-Gerhard Haupt/Jürgen Kocka (eds.), Comparative and Transnational History. Central European Approaches and new Perspectives (New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2009), online at https://archive.org/details/comparativetrans0000unse_y9v4 [06.11.2024]; Jürgen Kocka, “Comparative History: Methodology and Ethos,” in: Benjamin Z. Kedar (ed.), Explorations in Comparative History (Jerusalem: Hebrew University Magnes Pres, 2009), pp. 29–36; James Mahoney/Dietrich Rueschemeyer (eds.), Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2003); Hannes Siegrist, “Comparative History of Cultures and Societies. From Cross-Societal Analysis to the Study of Intercultural Interdependencies,” in: Comparative Education 42 (2006), pp. 377–404; Thomas Welskopp, “Comparative History,” in: European History Online (EGO), 12.03.2010, http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/theories-and-methods/comparative-history/thomas-welskopp-comparative-history [06.11.2024]; James Mahoney/Kathleen Thelen (eds.), Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Hartmut Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen. Eine Einführung, (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2021) (revised new edition of: Historical Comparison. Eine Einführung zum 19. und 20. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt: Campus Fachbuch, 1999); Hartmut Kaelble, “Der historische Vergleich,” in: Stefan Haas (ed.), Handbuch Methoden der Geschichtswissenschaft (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2023), http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-27798-7_13-1 [06.11.2024].

[2] John Stuart Mill, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. Being a Connected View of the Principles of Evidence, and the Methods of Scientific Investigation (London: John W. Parker, 1843).

[3] Cf. Jürgen Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung der Welt. Eine Geschichte des 19.Jahrhunderts (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2009); Christopher A. Bayly, Die Geburt der modernen Welt. Eine Globalgeschichte 1780–1914 (Frankfurt /New York: Campus Verlag, 2006). The different approach to the Franco-German comparison becomes particularly clear in: Hélène Miard-Delacroix, Deutsch-französische Geschichte. 1963 bis zur Gegenwart (Darmstadt: wbg, 2011).

[4] Marc Bloch, “Pour une histoire comparée des sociétés européennes (1928),” in: Mélanges historiques, ed. by Charles-Edmond Perrin (Paris: S.E.V.P.E.N, 1963), pp. 16–40; Osterhammel, ch. 12.

[5] Cf. Haupt, “Comparative History;” Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen, pp. 49c.; important for historical explanation: Jürgen Osterhammel, “Explanation: The Limits of Narrativism in Global History,” in: Stefanie Gänger/Jürgen Osterhammel (eds.) Rethinking Global History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024), online at https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009444002 [06.11.2024).

[6] Charles Tilly, Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1984), pp. 82c., 145c.

[7] Michel Espagne, Les transferts culturels franco-allemands, (Paris: PUF, 1999).

[8] Sebastian Conrad/Shalini Randeria (eds.), Jenseits des Eurozentrismus. Postkoloniale Perspektiven in den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften (Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus, 2002); Shalini Randeria, “Geteilte Geschichte und verwobenen Moderne,” in: Jörn Rüsen et al. (eds.), Zukunftsentwürfe. Ideen für eine Kultur der Veränderung (Frankfurt/New York: Campus 1999), pp. 87–96; broad approach including comparison: Dominic Sachsenmaier, “Global History,” Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 11.02.2010, http://docupedia.de/zg/sachsenmaier_global_history_v1_en_2010 [06.11.2024]; Gänger/Osterhammel (eds.) Rethinking Global History.

[9] Sebastian Conrad, Globalgeschichte. Eine Einführung (München: C.H. Beck, 2013), p. 70.

[10] Cf. Conrad, Globalgeschichte; Alessandro Stanziani, Tensions of Social History: Sources, Data, Actors and Models in Global Perspective (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023); Patrick Boucheron/Stéphane Gerson, France in the World. A New Global History (New York: Other Press, 2019).

[11] Akira Iriye/Pierre-Yves Saunier (eds.), The Palgrave Dictionary of Transnational History. From the mid–19th Century to the Present Day (Houndmills/New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), p. VIII.

[12] Cf. Johannes Paulmann, “Internationaler Vergleich und interkultureller Transfer. Zwei Forschungsansätze zur europäischen Geschichte des 18. bis 20. Jahrhunderts,” in: Historische Zeitschrift 267 (1998), pp. 649–685; Alexander C.T. Geppert/Andreas Mai, “Vergleich und Transfer im Vergleich,” in: Comparativ 10 (2000), pp. 95–111, online at https://www.comparativ.net/v2/article/view/1181/2596 [06.11.2024]; Matthias Middell, “Kulturtransfer und Historische Komparatistik – Thesen zu ihrem Verhältnis,” in: Comparativ 10 (2000), pp. 7-41, online at https://www.comparativ.net/v2/article/view/1177/1041 [06.11.2024]; Wilfried Loth/Jürgen Osterhammel (eds.), Internationale Geschichte. Themen – Ergebnisse – Aussichten (Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag, 2000); Albert Wirz, “Für eine transnationale Gesellschaftsgeschichte,” in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 27 (2001), pp. 489–498; Hartmut Kaelble, “Die interdisziplinären Debatten über Vergleich und Transfer,” in: id./Jürgen Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer. Komparatistik in den Sozial-, Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften (Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 2003), pp.469–494; Christiane Eisenberg, “Kulturtransfer als historischer Prozess,” in: Kaelble/Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer, pp. 399–417; Jürgen Osterhammel, “Transferanalyse und Vergleich im Fernverhältnis,” in: Kaelble/Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer, pp. 439–466; Hannes Siegrist, “Perspektiven der vergleichenden Geschichtswissenschaft. Gesellschaft, Kultur, Raum,” in: Kaelble/Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer, pp. 263-297; Patricia Clavin, “Defining Transnationalism,” in: Contemporary European History 14 (2005), pp. 421–439; Hannes Siegrist, “Transnationale Geschichte als Herausforderung der wissenschaftlichen Historiographie,” in: Connections, 16.02.2005, online at https://www.connections.clio-online.net/debate/id/fddebate-132113 [06.11.2024]; Hartmut Kaelble, “Die Debatte über Vergleich und Transfer und was jetzt?” in: Connections, 08.02.2005, online at http://www.connections.clio-online.net/debate/id/fddebate-132112 [06.11.2024]; Gunilla Budde/Sebastian Conrad/Oliver Janz (eds.), Transnationale Geschichte. Themen, Tendenzen und Theorien (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006); Ian Tyrrell, What is Transnational History? published on the website of Ian Tyrrell 2007, http://iantyrrell.wordpress.com/what-is-transnational-history/ [06.11.2024]; Kiran Klaus Patel, “Transnationale Geschichte,” in: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), Mainz, 03.12.2010, http://ieg-ego.eu/de/threads/theorien-und-methoden/transnationale-geschichte/klaus-kiran-patel-transnationale-geschichte [06.11.2024]; Konrad H. Jarausch, “Reflections on Transnational History,” in: H-German, 20.01.2006, https://lists.h-net.org/cgi-bin/logbrowse.pl?trx=vx&list=h-german&month=0601&week=c&msg=LPkNHirCm1xgSZQKHOGRXQ&user=&pw= [06.11.2024]; Madeleine Herren/Martin Rüesch/Christiane Sibille, Transcultural History. Theories, Methods, Sources (Heidelberg/Berlin: Springer, 2012); Margrit Pernau, Transnationale Geschichte (Göttingen: UTB, 2011); also: Wolfram Kaiser, “Brussels calling. Die Geschichte der Europäischen Union und die Gesellschaftsgeschichte Europas,” in: Arnd Bauerkämper/Hartmut Kaelble (eds.), Gesellschaft in der europäischen Integration seit den 1950er Jahren. Migration – Konsum – Sozialpolitik – Repräsentationen, (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012), pp. 43–62; Philipp Gassert, “Transnationale Geschichte,” Version: 2.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 29.10.2012, http://docupedia.de/zg/gassert_transnationale_geschichte_v2_de_2012 [06.11.2024]; Hans-Jürgen Lüsebrink, Interkulturelle Kommunikation. Interaktion, Fremdwahrnehmung, Kulturtransfer, 4th ed., (Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2016); Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen, pp.103–126.

[13] Pernau, Transnationale Geschichte, p. 53c.

[14] Michael Werner/Bénédicte Zimmermann, “Vergleich, Transfer, Verflechtung. Der Ansatz der Histoire croisée und die Herausforderung des Transnationalen,” in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 28 (2002), pp. 607–636.

[15] Cf. Bloch, “Pour une histoire comparée des sociétés européennes (1928);” Otto Hintze, Soziologie und Geschichte. Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur Soziologie, Politik und Theorie der Geschichte, vol. 2, 2nd ed. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1964), p. 251. Cf. as an example of a classic sociological comparison of Max Weber: Hinnerk Bruhns/Wilfried Nippel (eds.), Max Weber und die Stadt im Kulturvergleich (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000).

[16] Cf. Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen, pp. 167c.

[17] Cf. Willibald Steinmetz (ed.), The Force of Comparison. A new Perspective on Modern European History and the Contemporary World (New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2019); Angelika Epple/Walter Erhart (eds.), Die Welt beobachten. Praktiken des Vergleichens, (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 2015).

[18] Cf. Jörn Leonhard, “Nationen und Emotionen nach dem Zeitalter der Extreme – Deutschland und Frankreich im 20. Jahrhundert,” in: id. (ed.), Vergleich und Verflechtung. Deutschland und Frankreich im 20. Jahrhundert (Berlin: Erich Schmidt Verlag, 2015), pp. 7–25, online at https://freidok.uni-freiburg.de/data/12790 [06.11.2024].

[19] Cf. for many examples of studies: Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen, pp. 103c.

[20] Cf. Peter Schöttler, “Die deutsche ‘Westforschung’ der 1930er Jahre zwischen ‘Abwehrkampf’ und territorialer Offensive,” in: id. (ed.), Geschichtsschreibung als Legitimationswissenschaft 1918-1945 (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1997), pp. 204–226; Karl Ditt, “Die Kulturraumforschung zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik. Das Beispiel Franz Petri (1903-1993),” in: Westfälische Forschungen 46 (1996), pp. 73–176; Konrad H. Jarausch/Hannes Siegrist (eds.), Amerikanisierung und Sowjetisierung in Deutschland 1945–1970, (Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 1997).

[21] Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen, pp. 172c.

[22] In addition to world-historical syntheses mentioned above, cf. some further examples: Dominic Sachsenmaier, Global Perspectives on Global History. Theories and Approaches in a Connected World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Isabella Löhr, Die Globalisierung geistiger Eigentumsrechte. Neue Strukturen internationaler Zusammenarbeit 1886–1952 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2010); Andreas Weiß, Asiaten in Europa, Begegnungen zwischen Asiaten und Europäern 1880–1914 (Paderborn: Brill Schöningh, 2016); Kristin Meißner, Strategische Experten. Die imperialpolitische Rolle von ausländischen Beratern in Meiji-Japan (1868–1912) (Frankfurt/New York: Campus Verlag, 2018); Jürgen Osterhammel, Unfabling the East: The Enlightenment's Encounter with Asia (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018); Christian Methfessel, Kontroverse Gewalt. Die imperiale Expansion in der englischen und deutschen Presse vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg (Vienna/Cologne/Weimar: Böhlau, 2019); Christof Dejung/David Motadel/Jürgen Osterhammel (eds.), The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Andrew B. Liu, Tea War: A History of Capitalism in China and India (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2020).

[23] See, among others, Nicolas Delalande/Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel/Pierre Singaravélou/Marie-Bénédicte Vincent (eds.), Dictionnaire historique de la comparaison (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2020). Christophe Charle, the French historical comparatist with the most publications, has published several European comparative studies on intellectuals, empires, theatre and cultures since the 1990s (cf. ibid., p. 302).

[24] Cf. Reinhard Bendix, Herrschaft und Industriearbeit. Untersuchungen über Liberalismus und Autokratie in der Geschichte der Industrialisierung (Frankfurt: Europäische Verlagsanstalt, 1960); Barrington Moore, Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966); Tilly, Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons; Stein Rokkan, Vergleichende Sozialwissenschaft: Die Entwicklung der inter-kulturellen, inter-gesellschaftlichen und inter-nationalen Forschung. Hauptströmungen der sozialwissenschaftlichen Forschung (Frankfurt: Ullstein, 1972); Theda Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia, and China (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979); Peter Flora (ed.), Stein Rokkan: Staat, Nation und Demokratie in Europa. Die Theorie Stein Rokkans aus seinen gesammelten Werken rekonstruiert und eingeleitet von Peter Flora (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp 2000).

[25] Cf. Dominic Sachsenmaier, Global Perspectives on Global History. Theories and Approaches in a Connected World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 59c., here 110c., 122c.

[26] Cf. Stefan Immerfall, “Europäischer Gesellschaftsvergleich,” in: Maurizio Bach/Barbara Hönig (eds.), Europasoziologie. Handbuch für Wissenschaft und Studium (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2018), pp. 470–478; Klaus von Beyme, Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft (Wiesbaden: VS, 2010); James Mahoney/Kathleen Thelen (eds.), Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

[27] Particularly informative in this regard: Osterhammel, “Transferanalyse und Vergleich im Fernverhältnis,” in: Kaelble/Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer; Osterhammel, “Explanation: The Limits of Narrativism in Global History,” in: Gänger/Osterhammel (eds.), Rethinking Global History.

Agnes Arndt/Joachim C. Häberlen/Christiane Reinecke (eds.), Vergleichen, verflechten, verwirren? Europäische Geschichtsschreibung zwischen Theorie und Praxis, Göttingen 2011

Marc Bloch, “Pour une histoire comparée des sociétés européennes (1928),” in: id., Mélanges historiques, ed. Charles-Edmond Perrin, Paris 1963, p. 16-40

Heinz-Gerhard Haupt/Jürgen Kocka (eds.), Comparative and Transnational History. Central European Approaches and new Perspectives, New York/Oxford 2009, online at https://archive.org/details/comparativetrans0000unse_y9v4 [06.11.2024]

Hartmut Kaelble, Historisch Vergleichen. Eine Einführung, Frankfurt a.M. 2021

Matthias Middell, “Kulturtransfer, Transfers culturels,” Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 28.01.2016, http://docupedia.de/zg/middell_kulturtransfer_v1_de_2016 [06.11.2024]

Matthias Middell, “Transregional Studies: A new Approach to Global Processes,” in: Matthias Middell (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Transregional Studies, London/New York 2019, p. 1-16

James Mahoney/Kathleen Thelen (eds.), Advances in Comparative-Historical Analysis, Cambridge 2015

Jürgen Osterhammel, “Transferanalyse und Vergleich im Fernverhältnis,” in: Hartmut Kaelble/Jürgen Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer. Komparatistik in den Sozial-, Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 2003, p. 439-466

Hannes Siegrist, “Perspektiven der vergleichenden Geschichtswissenschaft. Gesellschaft, Kultur, Raum,” in: Hartmut Kaelble/Jürgen Schriewer (eds.), Vergleich und Transfer. Komparatistik in den Sozial-, Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 2003, p. 263-297

Thomas Welskopp, “Comparative History,” in: European History Online (EGO), 12.03.2010, http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/theories-and-methods/comparative-history/thomas-welskopp-comparative-history [06.11.2024]

Michael Werner/Bénédicte Zimmermann, “Vergleich, Transfer, Verflechtung. Der Ansatz der Histoire croisée und die Herausforderung des Transnationalen,” in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 28 (2002), S. 607-636

Michael Werner/Bénédicte Zimmermann, “Beyond comparison: Histoire croisée and the challenge of reflexivity,” in: History and Theory, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2006, p. 30-50

Copyright © 2024 - Lizenz:

Clio-online – Historisches Fachinformationssystem e.V. und Autor:in, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk ist zum Download und zur Vervielfältigung für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke freigegeben. Es darf jedoch nur erneut veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der o.g. Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Dies betrifft auch die Übersetzungsrechte. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: redaktion@docupedia.de.