Publikationsserver des Leibniz-Zentrums für

Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam

e.V.

Archiv-Version

Visual History (english version)

Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 07.11.2011 https://docupedia.de/paul_visual_history_v1_en_2011

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.2.792.v1

Fields of research, terms, capacity, desiderata

By expanding historical image research, visual history has in the recent past established itself as a field of research in late modern and contemporary history, which considers images in a wider sense both as sources as well as independent artifacts of historiographical research and likewise looks at the visuality of history and the historicity of the visual. Its exponents advocate understanding images beyond their pictorialness as a medium and as an activity with an independent aesthetic that condition the way of seeing things, shape perceptual patterns, convey interpretations, that organize the aesthetic relationship of historic subjects to their social and political reality and which are able to generate own realities. Visual History in this sense is thus more than an additive expansion of the canon of history studies or the history of visual media. It addresses the whole field of visual practice as well as the visuality of experience and history. Methodologically, the research design of visual history is transdisciplinary and has an open structure. Depending on the object of study, it uses in particular methods of art history, media and communication science.[1]

Historical studies in the visual turn

In the past few years, visual productions and practices have gained the attention of German-speaking contemporary historians and have changed their research interests, topics, their work and presentation methods, so that David F. Crew could state in the Journal "German History" in 2009: "Yet German Historians have only recently begun to pay serious attention to the politics of images."[2] To Franz Becker, as well, the analysis of visual testimonies of the past has become "an integral element of all historical research that seeks not only to deal with (alleged) objective reality, but also with its subjective appropriation."[3] Photographs especially have caught the attention of historians.[4] If we compare anthologies from 15 years ago[5] with the state of discussion today, then the assessments of Crew and Becker can be agreed with: History studies are no longer a bystander to the discussion of other disciplines, but actively take part in the discussion on the iconic or visual turn, respectively, in the humanities.[6]

This has been encouraged by several, mutually reinforcing developments: first and foremost the technological quantum leap of the world wide web and a collaterally looming paradigm shift within history studies. As a result, historians have had completely new possibilities of image research at their disposal for merely the last ten years.[7] While these used to be exclusive and costly undertakings that caused some historic research projects to fail for financial reasons alone, research has now become possible within short periods of time from one's own desk. This has tremendously encouraged the readiness to open up to visual sources of history. This is part of a general paradigm shift, especially in a generation of younger historians, who have grown up with modern visual media and for whom the dominance of the written word seems to have been replaced by the hegemony of images. This paradigm shift results from the fact that contemporary historiography today is in essence historiography of media society[8], which – as a consequence of the great visual revolutions of the 20th and early 21st century in the political and social realm – consequently also has to deal with visual testimonies.[9] Further reasons why contemporary historians are increasingly turning to images are the debates on the value of historical photographs as sources, as well as the handling of the material prompted by the so-called ”Wehrmachtsausstellung" in the 1990s[10], as well as the ”Image Wars" of the recent past, such as 9/11 or the continuing war in Iraq, which have manifested the meaning of images as both weapons and also shaping and generating forces in the political process.[11]

All this has increased the willingness of contemporary historians to make images sources and independent elements of historical research. In 2004 Thomas Lindenberger programmatically demanded conceiving of ”today's contemporaries [...] also as 'co-listeners' and 'co-seers' [...] in order to be able to suitably interpret their experiences and narratives. Their living environment was and is determined by the everyday presence of audiovisuals, their experience of reality also conveyed by the sounds of records and radio, the pictures in illustrated magazines, the moving (sound) pictures in newsreels, movies and television."[12] Michael Wildt has recently referred to the resulting consequences for history studies and history didactics. As a result, the increased importance of the media has also changed "the mode of construction of history as well as the role of the academic historian." Images and sounds should "not just be included in the work of historians as sources – images change the handling of history and the genesis of historical awareness."[13]

Similar to francophone history studies on the 20th century[14], modern history and contemporary history in German-speaking countries, too, have seen considerable movement, as, for example, a look at the "Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History" and its publications of visual images demonstrates.[15] As regards content, most of these studies focus on five levels: (1.) context and functional analysis, where based on historiographic source criticism production conditions, genesis and functions of historic pictures are analyzed; (2.) the actual product analysis, e.g. the analysis of semiology, semantics and, if need be, on the pragmatism of visual testimonies; (3.) the analysis of iconization processes, i.e. the question of how and why certain images advance to become icons of the cultural memory; (4.) the analyses of processes of interpicturality and media transfer, that is, the question of how certain subjects and motifs communicate with other images and move through the world of images or, respectively, enter into other media and as a result of this transfer change their original meaning, as well as (5.) the audience and use analysis, i.e. the question of how images are utilized, functionalized and refunctioned within cultural memory and for identity construction.

Overall, three developments and foci in newer historical studies of images can be distinguished, which partly replace each other, partly superimpose and partly correspond to differing understandings of images: images as sources, images as media and images as generative powers.

Images as sources

Drawing on older research of historic images, particularly established in medieval studies and early modern history[16], in which images, for a long time and on a high level, have been used as sources and objects of historical knowledge[17], newer endeavors primarily strove to develop images as additional sources in contemporary history research which it was hitherto lacking, for historic research questions often inspired by cultural science, as well as for sources of contemporary perspectives, for social and cultural points of view, to use them as media of interpretation and thus also as sources of the history of memory. "Images can be used as a historic source beyond transmitting personal or factual information," wrote for example Brigitte Tolkemitt in 1991. "Especially as a non-verbal medium with a primarily affective impact, they seem suitable as a supplement and corrective to written sources."[18]

Even in 1995, Irmgard Wilharm complained that the truism that cultural transmission is carried out not only through the written word, but increasingly through images, was far from being generally accepted by historians.[19] Frank Kämpfer – a pioneer of newer historic image research[20] – argued two years later in the first volume of his ”Imaginarium des 20. Jahrhunderts": "Reflection on three-thousand years of evolved image culture in Europe has for a long time been delegated from history studies to art historians."[21] In contrast, it can now be asserted that contemporary historians are well aware of images as sources. A look at the composition and content of Andreas Wirsching's textbook, "Neueste Geschichte," published in 2006, shows that this is more than a mere temporary fad. He writes on the extended canon of historic sources: "In addition to classic recorded history, media of all kinds have come into view. And complementing the still dominating written sources, figurative, physical and – in contemporary history – oral sources (oral history) have emerged."[22] That the art historian Horst Bredekamp gave the closing speech at the 2006 Konstanzer Historikertag was only consequential in light of this development.[23]

A positive aspect of this development is that the whole field of moving and static images is gaining the attention of historians. An additional positive feature is that in dealing with images in general and photographs in particular as sources of historiographic insight, no close-knit methodology has established itself, but rather a method pluralism is practiced, which, depending on the objects of investigation, uses iconographic-iconological methods, semiotic approaches, as well as sociological methods.[24] Since the late 1980s, this "Wald- und Wiesenweg," i.e. unconventional approach (K. Hartewig) has yielded a wealth of convincing documentaries, illustrations and analysis, especially in the areas of social, military and revolutionary history, the history of domination, education and everday life.[25]

Even though it is commonplace in modern history didactics for contemporary images to be on an equal footing with historic written sources and they in no way constitute an accurate copy of historical reality but require interpretation and ideology-critical decryption,[26] this approach does not yet reflect practice in school history lessons and textbooks. To date, images are primarily used as eye-catchers, stopgaps or pure illustrations, and furthermore the majority of captions are insufficient or utterly wrong and images retouched and cropped. However, progress in history didactics can be seen and images are increasingly used as sources to acquire image historical competence[27] and in methods of interpreting visual sources (caricatures, posters, photographs, movies).[28]

Despite this progress in analysis and use of images as sources, desiderates and problems remain. The focus of historical image research on the static image in the form of paintings, posters and photographs is not only justified. In fact, it also expresses a vague fear of the moving images of movies[29] and electronic images of television that have yet to see convincing historiographic research efforts and forms of publication that do justice to the aesthetic characteristics and qualities of these media. These significant gaps, however, can also be seen in the field of photo-historical research. Even though without doubt private and snapshot photography comprises the ”most comprehensive pool of pictorial stories of private life,"[30] this is an ”especially hidden area" of historians' engagement with images.[31] The explosiveness and significance, especially of private photography, was not least demonstrated by the discussion surrounding the photographs in the "Wehrmachtsausstellung." Cord Pagenstecher rightfully called for considering private photo albums as autobiographic sources and the use of them in the analysis of contemporary perception and self-portrayal, analogous to the biographic approach of oral history.[32] As with private photography, color photography, too, is terra incognita in historic image research.[33] And finally, major historical photographic collections like those of the World War II ”Propagandakompanien" in the German Federal Archives have not even been rudimentarily explored. Just as even a systematic exploration of the history of photography and picture-taking between 1933 and 1945 in particular and a comprehensive analysis of the national-socialist use of images in general are lacking to date. Furthermore, the academic debate on photography is still strongly shaped by a national focus. Intercultural comparisons such as the analysis of World War I war images in German and French newspapers and magazines or research into war photography in Spanish and French magazines during the Spanish Civil War[34] are still scarce. Finally, other static visual sources such as postage stamps have hardly received attention from historic image research, even though they force themselves on historic-political cultural research.[35]

Several image historic publications, as well as the use of images in history classes, show that images are rarely looked at as a self-referential system with a significant aesthetic quality and a unique meaning of their own, which do not primarily function as a symbol to point to something outside of the image, but rather refer to themselves. By looking at external references, the image and its self-reference no longer find themselves at the center of historiographic considerations. The image remains solely a window into another world and at best functions as a trigger. In this spirit, Martina Heßler rightfully criticized that historians as a rule still prioritize images as "historic sources" and see them as content without granting the aesthetic a meaningful role of its own.[36] Frank Becker, too, argues that the meaning of image elements does not inevitably follow from a context analysis. It should not be delegated to art history, but should be integrated constitutively into historiographic image research.[37] And finally, Christoph Hamann convincingly criticizes Hans-Jürgen Pandel and Michael Sauer's newer efforts in history didactics, arguing that while acknowledging the aesthetic, they would not grant it an "independent semantic status within the framework of the cognitive realization of the past." Insufficient light is shed upon the cognitive or semantic dimension of the aesthetic, respectively.[38]

Seldom have images with their specific aesthetics found themselves to be objects of investigation as independent and active areas of the political and cultural and as an interpreting medium. And seldom – with the exception of Alf Lüdtke's analysis of workers' photographs – has the unique sense of photographs been noted that does not develop from the photographer's intention or the ostensible interpretation of the historian.[39] That images are not only representations or outright mirrors of something that has happened and do not only passively reflect history, but shape and partly generate history themselves, thus remained largely outside historiographical understanding.

Images as media

Since the 1980s and 90s, impulses to broaden the approach to the visuality of history as an independent research area, as well as of the image as a communicative medium and a self-referential aesthetic system, have come mainly from the related fields of teaching, research and work, both at home and abroad, such as the Anglo-Saxon visual culture studies and art history.[40] In West Germany, history studies were encouraged by neighboring disciplines, such as empirical cultural studies and political science in the 1980s, which dealt with topics regarding meaning and impact of images, visual scenarios and symbols in the political and social movements of the 20th century and thus also with questions of visual politics. In the 1990s, particularly memory studies emphasized the relevance of images as "driving forces of tradition" and "myth machines," as well as the mediality of historic references.

Most notably, Horst Bredekamp, with his notion of the "active image" and his recent studies, fueled the iconic turn within history studies. According to him, historians, together with large portions of art history, are part of a tradition leading back to Plato and his Allegory of the Cave, which describes images as epiphenomena. Images, however, are not epiphenomena. They do not duplicate, but rather create what they show.[41] For Bredekamp, images relate "to the world of events equally in a reacting and shaping relationship," which is what often makes it difficult to categorically distinguish between history and image history.[42] Images, according to Bredekamp, not only reflect history passively, but due to their specific "formative power of form"[43] are capable of shaping as does every action or instruction. At the Konstanzer Historikertag 2006, Bredekamp vehemently made historians take note of this autonomous power of the aesthetic as a unique factor that contributes to history.[44]

Since the 1980s, history studies have, at first tentatively, dealt with the "constructive contribution" of images. According to Alf Lüdtke, the interest shifted to the "constructive dimension both in producing and perceiving images."[45] Already in 1988, Jürgen Hannig focussed on the question of "How images make history."[46] ”Images write history," Rainer Rother programatically called his anthology on historians and the movies published in 1991.[47] In the meantime, history didactics, too, began to notice the meaning of the constructive contribution of images to historical culture and demanded their analysis in history classes. For example, it is stated in a newer anthology: "Historical or historiographical images, respectively, will in the future have to be analyzed and examined objectively beyond their relevance as source material, with a stronger focus on their function in historical culture and regarding their specific strategies and intentions. Their inherent capacity to deconstruct possible history narratives will grow more important in the future."[48] Especially the Berlin-based specialist of history didactics, Christoph Hamann, has overcome the narrow understanding of images of previous history didactics and its fixation on the reflection and convincingly demonstrated in several publications the meaningful role of the aesthetic.[49]

For the analysis and use of images, this also includes taking images as active entities more seriously: as "driving forces of tradition" and "myth machines," that is to say as media of politics of history and memory which generate and carry a certain interpretation of history.[50] And also as media of commercial advertising, political propaganda and as a means of safeguarding power, as well as a medium of collective identity formation which social and political collectives use to try to develop and secure their identity.

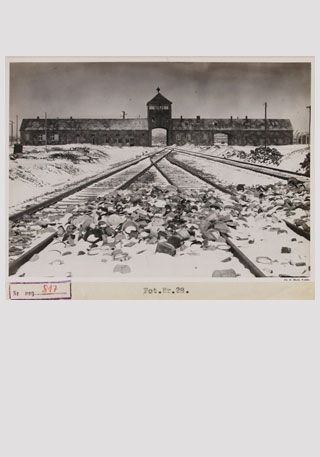

The first persons to demonstrate this for history and memory politics in larger publications were Cornelia Brink in her pioneering study on "Ikonen der Vernichtung" ("Icons of Destruction") on the public use of photographs of the Nazi concentration camps in post-war Germany[51] and Habbo Knoch in his voluminous work "The Act as Image" on the history of memory of National Socialism.[52] A number of studies on single images and image series' and their contribution to cultural memory, as well as analyses on how the trade or collectible Cards of the early 20th century shaped history, followed these studies. This includes studies on soldiers' snapshot photographs taken during the 1914 Christmas Truce and their prominence in the distinctive culture of remembrance of the former World War I opponents, studies on the prominence of central icons of American society such as the "Migrant Mother" by Dorothea Lange and the "Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima" photograph by Joe Rosenthal, the exemplary analysis of the picture of the Gatehouse of Auschwitz-Birkenau taken by the Polish photographer Stanisław Mucha immediately after the liberation, which shows neither perpetrators nor victims and for a long time provided the aesthetic foundation to the structuralist view of the Holocaust, contemplations on the "Trümmerfrau," a symbol invented by the National Socialists as a "visual construct" and successfully passed down to the present day, the reconstruction of the transcultural cultural flow of the military photographs of the Hiroshima nuclear explosion in the USA, Japan and in Europe, the deconstruction of the skewed interpretation of the photograph of the so-called carpet-scene during the founding phase of the Federal Republic, which haunts contemporary federal historiography and will not go away.[53] Large gaps in the expanding field of visual memory and history politics research can still be found in the area of popular history representation in exhibitions, museums and especially on television.[54]

Studies on the varying visual practices, that is to say on the social, political and cultural use of images as they are numerously found in cultural studies,[55] are still the exception within history studies. Similar things can be said of studies on the visual exercise of power such as snapshot practices during World War II, the use of images in National Socialist ruling institutions regarding the deportation of Jews or the defamation of the assassins of July 20, 1944 in front of the "People's Court."[56] Outstanding in this context is surely the analysis of the Göttingen-based historian Karin Hartewig of the photographic practices of the Ministry for State Security of the GDR and its considerable collection of photographs.[57]

In contrast to Anglo-Saxon countries, there are currently only a few historiographic studies on the role of the image in collective identity formation processes.[58] An exemplary analysis can be found in Ulrike Pilarczyk's work on the role of private photography in community and identity formation in the Jewish youth movement and the Zionist educational methods in Germany and Palestine after 1933.[59]

Studies on historic ”visual cultures" are still rare in German history studies. These would have to consider that visual culture[60] has not only become a central element of people's daily routines in the 20th and early 21st century, but also a form of being of everyday life.[61] Visual culture, according to Susanne Regener, does not deal with individual images alone, "but with the modern and postmodern tendency to visualize being and existence at all."[62] In contrast to art history, visual culture studies do not focus their interest on individual visual objects, but on the practices of producing, seeing and perceiving and thus on visuality as a medium, in which, according to William J.T. Mitchell, "politics are conducted."[63] At best, the anthology of Karin Hartewig and Alf Lüdtke "Die DDR im Bild,"[64] which integrates differing methodological approaches, can at present be seen as a part of visual culture Studies. It addresses the photography of the Weimar Republic, the photographic portrayal of competitive sports in the GDR, the observation of the transit highway, photography in factories, as well as the search for "Eigen-Sinn" (stubborn self-reliance) stubbo in the amateur photography of the GDR. Comparable studies on the visual cultures of the Weimar Republic, National Socialism and the Federal Republic before and after 1990 from a historical perspective are missing and desirable.[65]

Images as a formative power

Yet images are more than sources that refer to circumstances or events outside their own existence; they are more than media that transport meaning or generate significance through their aesthetic potential; images also have the ability to first create realities. Accordingly, they have an energetic and generative power not sufficiently taken into account by history studies and art history. To describe this, Horst Bredekamp introduced the term "Bildakt".[66] Image acts create facts by producing images. Especially "distinctive images," such as those of 9/11, possess "the same power as sword thrusts or punches."[67] Beyond the concrete image, the performative act connected to the image that creates a new reality is of importance. Such distinctive, palpable images can likewise be communicated through photographs and film clips, posters and video sequences; they can be of a fictional or non-fictional, an artistic or documentary nature. Due to their special aesthetics and meaning, they are capable of triggering individual or collective reactions, respectively, such as pain or protest irrespective of their material medium. Especially provoking images that run counter to the every day use of image, pathos formulas that build on internalized image patterns, as well as icons of power that emerge from the political iconosphere seem to inherently possess such energetic powers.

Propagandists and totalitarian regimes in the 20th century repeatedly and systematically availed themselves of the energetic power of images – whether in the implementation of a concept of the enemy and the visualization of political utopia or the staging of mass protests. Distinctive imagery of the enemy always included a call to action – of Prussian militarism of the Allied Forces in World War I, of post-war ”Black Shame," of the Jew in the anti-semitic "Final Solution" propaganda of the Nazis, of the Bolsheviks in the anti-communist image rhetoric after 1917 or of the Other or the Islamist, respectively, in present enemy construction[68] – just as the visualization of the "Arian" ideal body[69] or the classless communist society structurally included mechanisms of exclusion and destruction. In an interplay between glances, projections and images, this imagery can, under certain circumstances, unfold. Slowly, History Studies are beginning to discover the meaning of created joint experiences and the visualization of mass body through mass staging and the aesthetic experience connected to it, as for example in National Socialism.[70] A visual history of the 20th century must investigate such movements and their imagery much more precisely as image generating powers and especially understand image and event or image and act as a unit and not as separate entities.

Contemporary politics, as well as retroactive history and memory politics, have seen downright confrontations over individual distinctive images or image sequences, where images referred to one another, overwriting images with other images or positioning them against each other.[71] Such image wars were also fought out on the streets and often escalated to open violence – in the Weimar Republic following the screening of the anti-war classic ”All Quiet on the Western Front" or following the opening of the "Wehrmachtsausstellung" in the Federal Republic in the 1990s.[72] A series of interesting studies exists on these and other image wars, for example on the dispute over the colors and symbols of the first German Republic, on the allegorical national female figures in the image wars of the first post-war years, on the publicized symbolic images and the symbol war in the ”decisive year" 1932, on the image war concerning the interpretation of the World War and the defeat of 1918 or on the image wars and coming to terms with the Holocaust within the framework of "visual denazification" by the Allied Forces after 1945.[73] All these studies assign an active, meaningful as well as shaping role to images in the political process, the meaning of which would have to be individually further elaborated upon.

Image acts of special efficacy can be of both a non-fictional or fictional nature. This certainly includes photographs of the ”Sonderkommando Auschwitz" which documented the killing in the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the taking of photographs in and of itself became an act of resistance and gave the indescribable an image[74], as well as the broadcasting of the fictitious miniseries ”Holocaust" on German television in 1979, which did not shy away from showing the supposedly indescribable in impressive fictitious film sequences. "If ever one can talk of 'image acts'," wrote Bredekamp, "then when referring to these events."[75] With its image sequences, "Holocaust" gave the genocide of European Jewry a communicable image that was able to put an end to the silence present in the post-dictatorial society of perpetrators and made visual-medial products an integral element of the cultural memory. Just like the "Wehrmachtsausstellung," the broadcast led to direct physical acts of violence including bomb attacks.

The Islamist image acts of recent years – the destruction of the "Buddhas of Bamiyan," the images of the attack on the Twin Towers and the execution videos of Islamist terror groups – as well as, partially a response to the latter, the backlighted photographs of Bagdad burning in 2003, the digital torture photographs of Abu Ghraib and the Danish Mohammed caricatures[76] are at present the culmination of such image generating developments. The image does not only generate an own reality that prompts reaction, it becomes an action in and of itself. Especially the ”new wars" of the present, such as the on-going Iraq War, are proof for Bredekamp that the fact-creating, performative image act is as effective today as the use of weapons themselves. We currently see images "that do not portray the events, but create them." The purpose of decapitation is, for example, no longer solely to kill a prisoner, but the image act that reaches the eye of the beholder. Human beings are killed to enable them to become images. Therewith the act of viewing images produced in this way itself becomes an act of participation.[77]

Such image acts and related changes in the status of the beholder have, however, so far barely become an object of historiographic investigation. A visual history of the 20th and the early 21st centuries would have to dedicate itself to this generative power of images and simultaneously open itself to historiographic image act research that also understands images as image acts which themselves in turn generate history.

Visual History as a transdisciplinary research field

Unlike historic image research, the emerging field of visual history acts on the assumption of a multi-layered image concept that understands images as signs and sources, as media generating significance and interpretation through their aesthetic quality, and as an image act creating reality.

Although Gerhard Jagschitz – who was the first to use the term in German-speaking countries[78] – limited visual history to the medium of photography, it seems reasonable to subsume the whole spectrum of historiograhic dealings with products and practices of visual media under this concept and to follow the image concept as it is understood by visual culture studies. This does not envisage a hierarchy of visual sources, but rather includes visual artifacts of older visual media, such as posters, picture postcards and magazine caricatures, as well as photographs and movies and the modern electronic images of television and the internet. Above all, visual history studies the type and impact of image formation and use. It is thus much more than a simple illustration of history as it is currently practiced under the heading ”visual contemporary history."[79]

Furthermore, visual history is "not a finished method" and certainly not the silver bullet in the handling of images by historians. As in visual culture studies, it rather describes a transdisciplinary research field within history studies and a framework within which the meaning of images in history can adequately be dealt with and which welcomes support from various disciplines – starting with art history, and spanning communication and media science, political science and sociology, all the way to general visual science. Its goal is to understand the complex link between image structure, production, distribution and reception, as well as the establishment of tradition in history. The two-volume image atlas on the 20th and early 21st centuries published in 2008/09 illustrates the path that a visual history understood this way could take.[80]

German Version: Gerhard Paul, Visual History, Version: 3.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 13.03.2014

Gatehouse Auschwitz-Birkenau: Stanislaw Mucha (Kraków), gatehouse Auschwitz-Birkenau, taken after the liberation of the camp mid-February/mid-March 1945. The picture shows the gate house of the extermination camp from the perspective of the so-called "Rampe". The edge of the photograph clearly shows the barbed wire fence heading towards the viewer. This "Fot. Nr. 28" is from a photo album containing 38 pictures of the liberated camp, which Mucha has entrusted to the Museum Auschwitz. Panstwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau For more information see: Christoph Hamann, Fluchtpunkt Birkenau. Stanislaw Muchas Foto vom Torhaus Auschwitz-Birkenau (1945), in: Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.), Visual History. Ein Studienbuch, Göttingen 2006, p. 283-302.

Recommended Reading

Frank Becker, Historische Bildkunde – transdisziplinär, in: Historische Mitteilungen. 21 (2008), Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2008, ISSN 0936-5796, S. 95-110.

Horst Bredekamp, Schlussvortrag: BILD – AKT – GESCHICHTE, in: Geschichtsbilder. 46. Deutscher Historikertag vom 19.-22. September 2006 in Konstanz. Berichtsband. UVK, Konstanz 2007, ISBN 978-3-86764-014-5, S. 289-309.

Horst Bredekamp, Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil, in: Monika Flacke (Hrsg.), Mythen der Nationen. 1945 – Arena der Erinnerungen. Zabern, Mainz 2004, ISBN 3-8053-3298-X, S. 29-66.

Christoph Hamann, Visual History und Geschichtsdidaktik. Bildkompetenz in der historisch-politischen Bildung, Centaurus, Herbolzheim 2007, ISBN 978-3-8255-0687-2.

Jens Jäger, Fotografie und Geschichte, Campus, Frankfurt a. M. 2009, ISBN 978-3-593-38880-9.

Jens Jäger, Martin Knauer (Hrsg.), Bilder als historische Quellen? Dimensionen der Debatten um historische Bildforschung, Fink, München 2009, ISBN 978-3-7705-4758-6.

Gerhard Jagschitz, Visual History, in: Das audiovisuelle Archiv. Nr. 29/30, AGAVA, Wien 1991, S. 23-51.

Frank Kämpfer, 20th Century Imaginarium, 1-4, Kämpfer, Hamburg 1997-2002, ISBN 3-932208-04-8.

Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.), Visual History. Ein Studienbuch, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, Göttingen 2006, ISBN 978-3-525-36289-1.

Gerhard Paul, Visual History (english version), Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 7.11.2011, URL: http://docupedia.de/zg/Visual_History_.28english_version.29

Versions: 1.0

Copyright (c) 2023 Clio-online e.V. und Autor, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <redaktion@docupedia.de>

References

- ↑ For an elaborate view on the research field visual history see Gerhard Paul (ed.), Visual History. Ein Studienbuch, Göttingen 2006.

- ↑ David F. Crew, Visual Power? The Politics of Images in Twentieth-Century Germany and Austria-Hungary, in: German History 28.2 (2009) 28: 271-285, here 271.

- ↑ Frank Becker, Historische Bildkunde – transdisziplinär, in: Historische Mitteilungen 21 (2008): 95-110, here 95.

- ↑ See review of Jens Jäger, Fotografie und Geschichte, Frankfurt a. M. 2009; id., Fotografiegeschichte(n). Stand und Tendenzen der historischen Forschung, in: Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 48 (2008): 511-537.

- ↑ Irmgard Wilharm (ed.), Geschichte in Bildern. Von der Miniatur bis zum Film als historischer Quelle, Pfaffenweiler 1995.

- ↑ On the iconic turn in cultural studies see Doris Bachmann-Medick, Cultural Turns. Neuorientierungen in den Kulturwissenschaften, Reinbek 2006; Horst Bredekamp, Drehmomente – Merkmale und Ansprüche des iconic turn, in: Hubert Burda/Christa Maar (eds.), Iconic Turn. Die neue Macht der Bilder, Köln 2005: 15-26; Bernd Stiegler, „Iconic Turn“ und gesellschaftliche Reflexion, in: Trivium 1 (2008), online at http://trivium.revues.org/index391.html; as well as especially on the contribution from history studies: Jens Jäger, Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Klaus Sachs-Hombach (ed.), Bildwissenschaften. Disziplinen, Themen, Methoden, Frankfurt a.M. 2005: 185-195.

- ↑ See the links of the Austrian National Library on 17 image archives, picture agencies and photo-related websites http://www.onb.ac.at/sammlungen/bildarchiv/bildarchiv_links.htm, as well as the links „Digitalisierte Bildarchive“ of the University Library Frankfurt am Main http://www.ub.uni-frankfurt.de/musik/manskopf_links.html. A up-to-date collection of links of the most important databases for static and moving images would be an important tool for visual historians.

- ↑ See the workshop „Zeitgeschichte schreiben in der Gegenwart. Narrative – Medien – Adressaten,“ which was held at the Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung in Potsdam in March 2009, http://www.hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/tagungsberichte/id=2580; also see the article „Mediengeschichte“ by Annette Vowinckel on Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte http://docupedia.de/zg/Mediengeschichte.

- ↑ See Gerhard Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, 2 Vol.: Bildatlas I: 1900-1949, II: 1949 bis heute, Göttingen 2008-2009.

- ↑ See Sabine Hillebrecht, Bildquellen. Das Foto im Visier von Kunst und Kulturwissenschaftlern, Historikern und Archivaren, in: Fotogeschichte19.74 (1999): 68-70; Wolf Buchmann, „Woher kommt das Foto?“ Zur Authentizität und Interpretation von historischen Photoaufnahmen in Archiven, in: Der Archivar 59.4 (1999): 296-306; Anne Lena Mösken, „Die Täter im Blick“. Neue Erinnerungsräume in den Bildern der Wehrmachtsausstellung, in: Inge Stephan/Alexandra Tacke (eds.), NachBilder des Holocaust, Köln 2007: 235-252.

- ↑ See Bernd Hüppauf, Foltern mit der Kamera. Was zeigen Fotos aus dem Irak-Krieg, in: Fotogeschichte 24.93 (2004): 51-59; Gerhard Paul, Bilder des Krieges – Krieg der Bilder. Die Visualisierung des modernen Krieges, Paderborn 2004: 433-468; id., Der Bilderkrieg. Inszenierungen, Bilder und Perspektiven der „Operation Irakische Freiheit“, Göttingen 2005, as well as from a political science perspective the chapter „Bilder als Waffen: der Krieg und die Medien“ in Herfried Münkler, Der Wandel des Krieges. Von der Symmetrie zur Asymmetrie, Weilerswist 2006. 189-208.

- ↑ Thomas Lindenberger, Vergangenes Hören und Sehen. Zeitgeschichte und ihre Herausforderung durch die audiovisuellen Medien, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 1.1. (2004): 72-85, here 78, online at http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/16126041-Lindenberger-1-2004.

- ↑ Michael Wildt, Die Epochenzäsur 1989/90 und die NS-Historiographie, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History (2008) 5 (3), online at http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/16126041-Wildt-3-2008.

- ↑ Daniela Kneissl, L’historien saisi par l’image: Bildzeugnisse als Forschungsgegenstand in der französischsprachigen Geschichtswissenschaft des 20. Jahrhunderts, in: Jens Jäger/Martin Knauer (eds.), Bilder als historische Quellen? Dimensionen der Debatten um historische Bildforschung, München 2009: 149-199, here 189.

- ↑ The journal‘s archive can be found at http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/site/40208121/default.aspx.

- ↑ On the history of historic image research in general: Jens Jäger, Zwischen Bildkunde und Historischer Bildforschung. Historiker und visuelle Quellen 1880-1930, in: id./Knauer (eds.), Bilder als historische Quellen?: 45-69; Lucas Burkhart, Verworfene Inspiration. Die Bildgeschichte Percy Ernst Schramms und die Kulturwissenschaft Aby Warburgs, id.:71-96; Martin Knauer, Drei Einzelgänge(r): Bildbegriff und Bildpraxis der deutschen Historiker Percy Schramm, Helmut Boockmann und Rainer Wohlfeil (1945-1990), id.: 97-124.

- ↑ See the general overview by Jäger, Geschichtswissenschaft: 187.

- ↑ Brigitte Tolkemitt, Einleitung, in: id./Rainer Wohlfeil (eds.), Historische Bildkunde. Probleme – Wege – Beispiele, Berlin 1991: 7-14, here 9.

- ↑ Wilharm (ed.), Geschichte in Bildern: 9.

- ↑ Klaus Topitsch/Anke Brekerbohn (eds.), „Der Schuß aus dem Bild“. Für Frank Kämpfer zum 65. Geburtstag. Virtuelle Fachbibliothek Osteuropa. Digitale Osteuropa- Bibliothek: Reihe Geschichte 11 (2004), http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/558/.

- ↑ Frank Kämpfer, Einleitung, in: id., Propaganda. Politische Bilder im 20. Jahrhundert, bildkundliche Essays (= 20th Century Imaginarium, Vol. 1), Hamburg 1997: 6-7, here 6.

- ↑ Andreas Wirsching, Zu diesem Buch, in: id. (ed.), Neueste Zeit (= Oldenbourg Lehrbuch Neueste Geschichte), München 2006: 7-12, here 8 (emphasis added G. P.); also see the first article on historic image research in a textbook on contemporary history by Thomas Hertfelder, Die Macht der Bilder. Historische Bildforschung, in: id.: 281-292.

- ↑ Horst Bredekamp, Schlussvortrag: BILD – AKT – GESCHICHTE, in: Geschichtsbilder. 46. Deutscher Historikertag vom 19.-22. September 2006 in Konstanz. Berichtsband, Konstanz 2007: 289-309.

- ↑ Karin Hartewig, Fotografien, in: Michael Maurer (ed.), Aufriß der Historischen Wissenschaften, Vol. 4: Quellen, Leipzig 2002: 427-448, here 442.

- ↑ One could for example cite publications by Diethart Kerbs (ed.), Revolution und Fotografie, Berlin 1918/19, Berlin 1989; id. (ed.), Auf den Straßen von Berlin. Der Fotograf Willy Römer (1887-1979), Bönen 2004; id./Walter Uka (eds.), Fotografie und Bildpublizistik in der Weimarer Republik, Bönen 2004; the exemplary documentation and analysis by Klaus Tenfelde (ed.), Bilder von Krupp. Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, München 1994; the dissertations of Andreas Fleischer written under the supervision of Frank Kämpfer, „Feind hört mit!” Propagandakampagnen des Zweiten Weltkrieges im Vergleich, Münster/Hamburg 1994, and Astrid Deilmann, Bild und Bildung. Fotografische Wissenschafts- und Technikberichterstattung in populären Illustrierten der Weimarer Republik (1919-1932), Osnabrück 2004; the image historic publications edited and written by the former director of the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst on Soviet photography of World War II, amonst others: Das mitfühlende Objektiv. Michail Sawin, Kriegsfotografie 1941-1945, Berlin 1998; Nach Berlin! Timofej Melnik, Kriegsfotografie 1941-1945, Berlin 1998; Foto-Feldpost. Geknipste Kriegserlebnisse 1939-1945, Berlin 2000; Diesseits – jenseits der Front: Michail Trachman, Kriegsfotografie 1941-1945, Berlin 2002; the contextualization and analysis of a film document on the deportation of Jews in Dresden by Norbert Haase/Stefi Jersch-Wenzel/Hermann Simon (eds.), Die Erinnerung hat ein Gesicht. Fotografien und Dokumente zur Judenverfolgung in Dresden 1933-1945, Leipzig 1998; the research on photographs of Jewish everyday life in the province by Gerhard Paul/Bettina Goldberg, Matrosenanzug – Davidstern. Bilder jüdischen Lebens aus der Provinz, Neumünster 2002; the documentation on photography as a means of National-Socialist persecution by Klaus Hesse/Philipp Sprenger, Vor aller Augen. Fotodokumente jüdischen Lebens in der Provinz, Essen 2002; the study mainly based on private foto albums by Cord Pagenstecher, Der bundesdeutsche Tourismus. Ansätze zu einer Visual History: Urlaubsprospekte, Reiseführer, Fotoalben 1950-1990, Hamburg 2003; as well as the publications of the Vienna-based photo historian and editor of the journal „Fotogeschichte“: Anton Holzer, Mit der Kamera bewaffnet. Krieg und Fotografie, Marburg 2003; id., Die andere Front. Fotografie und Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Darmstadt 2007; id., Das Lächeln der Henker. Der unbekannte Krieg gegen die Zivilbevölkerung 1914-1918, Darmstadt 2008.

- ↑ See f.ex. Klaus Bergmann/Gerhard Schneider, Das Bild, in: Hans-Jürgen Pandel/Gerhard Schneider (eds.), Handbuch Medien im Geschichtsunterricht, Schwalbach i.T. 1999: 211-254, here 212, 224.

- ↑ Ausführlich Reinhard Krammer/Heinrich Ammerer (eds.), Mit Bildern arbeiten. Historische Kompetenzen erwerben, Neuwied 2006; Christoph Hamann, Visual History und Geschichtsdidaktik. Bildkompetenz in der historisch-politischen Bildung, Herbolzheim 2007: 157.

- ↑ See f.ex. history books such as: Expedition Geschichte (Realschule Baden-Württemberg), Vol. 3: Von der Weimarer Republik bis zur Gegenwart, Uwe Uffelmann et al. (eds.), Frankfurt a. M. 2002; Das waren Zeiten, Vol. 4: Das 20. Jahrhundert, Ausgabe c, Dieter Brückner/Harald Focke (eds.), Bamberg 2005; Geschichte konkret. Ein Lern- und Arbeitsbuch, Vol.2, Hans-Jürgen Pande (eds.), Braunschweig 2007; fundamentally on the use of images in history lessons: Michael Sauer, Bilder im Geschichtsunterricht. Typen, Interpretationsmethoden, Unterrichtsverfahren, Seelze- Velber 32007.

- ↑ Günter Riederer, Film und Geschichtswissenschaft. Zum aktuellen Verhältnis einer schwierigen Beziehung, in: Paul (ed.), Visual History: 96-113.

- ↑ Tim Starl, as quoted by Marita Krauss, Kleine Welten. Alltagsfotografie – die Anschaulichkeit einer „privaten Praxis“, in: Paul (ed.), Visual History: 57-75.

- ↑ Krauss, Kleine Welten: 57.

- ↑ Pagenstecher, Der bundesdeutsche Tourismus. From an art history perspective, this has been demonstrated regarding private snapshot photography of World War II: Petra Bopp, Fremde im Visier. Fotoalben aus dem Zweiten Weltkrieg, Bielefeld 2009.

- ↑ See f.ex. for World War I: Marc Hansen: „Wirklichkeitsbilder“. Der Erste Weltkrieg in der Farbfotografie, in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Bildatlas I, S. 188-195, as well as on French color photography: Alain Fleischer et al. (eds.), Couleurs de guerre. Autochromes 1914-1918, Paris 2006.

- ↑ Thilo Eisermann, Pressephotographie und Informationskontrolle im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich (= 20th Century Imaginarium, Vol. 3), Hamburg 2000; Carolin Brothers, War and Photography. A Cultural History, London 1997.

- ↑ Michael Sauer, Originalbilder im Geschichtsunterricht. Briefmarken als historische Quellen, in: Gerhard Schneider (ed.), Die visuelle Dimension des Historischen, Schwalbach/Ts. 2002: 158-161.

- ↑ Martina Heßler, Bilder zwischen Kunst und Wissenschaft. Neue Herausforderungen für die Forschung, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 31 (2005): 266-292, here 272. On the meaningful role of the aesthetic see Gottfried Boehm, Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Die Macht des Zeigens, Berlin 2007; Axel Müller, Wie Bilder Sinn erzeugen. Plädoyer für eine andere Bildgeschichte, in: Stefan Majetschak, Bild-Zeichen. Perspektiven einer Wissenschaft vom Bild, München 2005: 77-96.

- ↑ Becker, Historische Bildkunde – transdisziplinär: 96.

- ↑ Hamann, Visual History und Geschichtsdidaktik: 170. Hamann explicitly excludes from his criticism Bodo von Borries, Geschichtslernen und Geschichtsbewußtsein. Empirische Erkundungen zu Erwerb und Gebrauch von Historie, Stuttgart 1988, who for a long time has demanded dealing with the aesthetic of image-related sources in history classes.

- ↑ Alf Lüdtke, Industriebilder – Bilder der Industriearbeit? Industrie- und Arbeiterphotographie von der Jahrhundertwende bis in die 1930er Jahre, in: Historische Anthropologie 1.3 (1993): 394-430; id., Industriebilder – Bilder der Industriearbeit? Industrie- und Arbeiterphotographie von der Jahrhundertwende bis in die 1930er Jahre, in: Wilharm (ed.), Geschichte in Bildern: 47-92; on the photograph by Theo Gaudig also see Walter Uka, AIZ. Arbeiteralltag im Spiegel der Arbeiter-Illustrierten-Zeitung, in: Paul (ed.): Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, Bildatlas I: 388-395.

- ↑ On the impulses from other disciplines see: Gerhard Paul, Von der Historischen Bildkunde zur Visual History. Eine Einführung, in: id. (ed.), Visual History: 7-36, hier 11.

- ↑ Bredekamp, Schlussvortrag: 309.

- ↑ Id., Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil, in: Monika Flacke (ed.), Mythen der Nationen. 1945 – Arena der Erinnerungen, Mainz 2004: 29-66.

- ↑ Bredekamp, Schlussvortrag: 305.

- ↑ Id.

- ↑ Alf Lüdtke, Kein Entkommen? Bilder-Codes und eigen-sinniges Fotografieren; eine Nachlese, in: Karin Hartewig/Alf Lüdtke (eds.), Die DDR im Bild. Zum Gebrauch der Fotografie im anderen deutschen Staat, Göttingen 2004: 227-236, here 227.

- ↑ Jürgen Hannig, Wie Bilder „Geschichte machen“. Dokumentarphotographie und Karikatur, in: Geschichte lernen 1.5 (1988): 49-53.

- ↑ Rainer Rother (ed.), Bilder schreiben Geschichte. Der Historiker im Kino, Berlin 1991.

- ↑ Reinhard Krammer/Heinrich Ammerer/Waltraud Schreiber, Vorwort, in: Krammer/Ammerer (eds.), Mit Bildern arbeiten, pp. 5-6, here p. 5.

- ↑ See f.ex. the analysis by Christoph Hamann in Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, 2 Vol.; id., Visual History und Geschichtsdidaktik.

- ↑ Bernd Roeck, Gefühlte Geschichte. Bilder haben einen übermächtigen Einfluss auf unsere Vorstellungen von Geschichte, in: Recherche. Zeitung für Wissenschaft, Wien 2 (2008).

- ↑ Cornelia Brink, Ikonen der Vernichtung. Öffentlicher Gebrauch von Fotografien aus nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern, Berlin 1998.

- ↑ Habbo Knoch, Die Tat als Bild. Fotografien des Holocaust in der deutschen Erinnerungskultur. Hamburg 2001.

- ↑ See f.ex. the articles by Bernhard Jussen, Christian Bunnenberg, Thomas Hertfelder, Jost Dülffer, Christoph Hamann, Gerhard Paul, Marita Krauss, Michael Ruck in Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, 2 Vol., whereas this is by no means a comprehenvise list, but rather shows in examples the spectrum of image historic studies in today‘s cultural memory.

- ↑ Cf. however: Barbara Korte/Sylvia Paletschek (eds.), History Goes Pop. Zur Repräsentation von Geschichte in populären Medien und Genres, Bielefeld 2009.

- ↑ See f.ex. Susanne Regener, Fotografische Erfassung: Zur Geschichte medialer Konstruktionen des Kriminellen, München 1999.

- ↑ Bernd Hüppauf, Der entleerte Blick der Kamera, in: Hannes Heer/Klaus Naumann (eds.), Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944, Hamburg 1995: 504-527; Klaus Hesse, Bilder lokaler Judendeportationen. Fotografien als Zugänge zur Alltagsgeschichte des NS-Terrors, in: Paul (ed.), Visual History: 149-168; Johannes Tuchel, Vor dem „Volksgerichtshof“. Schauprozesse vor laufender Kamera, in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Bildatlas I: 648-657.

- ↑ Karin Hartewig, Das Auge der Partei. Fotografie und Staatssicherheit, Berlin 2004.

- ↑ Ardis Cameron (ed.), Looking for America. The Visual Production of Nation and People, Malden, Mass. 2005. The articles by Cameron impressively demonstrate how national, social, ethnic of gender identity in the USA consistute themselves centrally via visual perception, that race, f.ex., is not only an ideological concept, but also a form of perception.

- ↑ Ulrike Pilarczyk, Gemeinschaft in Bildern. Jüdische Jugendbewegung und zionistische Erziehungspraxis in Deutschland und Palästina/Israel, Göttingen 2009; also see id., Fotografie als gemeinschaftsstiftendes Ritual. Bilder aus dem Kibbuz, in: Paragrana. Internationale Zeitschrift für Historische Anthropologie 121/2 (2003): 621-640.

- ↑ On the term see Nicholas Mirzoeff, An Introduction to Visual Culture, London 22009.

- ↑ Id., p. 3.

- ↑ Susanne Regener, Bilder / Geschichte. Theoretische Überlegungen zur Visuellen Kultur, in: Hartewig/Lüdtke (eds.), Die DDR im Bild: 13-26, here 13.

- ↑ William J.T. Mitchell, Interdisziplinarität und visuelle Kultur, in: Herta Wolf (ed.), Diskurse der Fotografie. Fotokritik am Ende des fotografischen Zeitalters, Vol. 2, Frankfurt a.M. 2003: 38-50, here 43.

- ↑ Karin Hartewig/Alf Lüdtke (eds.), Die DDR im Bild. Zum Gebrauch der Fotografie im anderen deutschen Staat, Göttingen 2004.

- ↑ From a media science or historic perspective, respectively, see Werner Faulstich (ed.), Kulturgeschichte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts, 8 Volumes, München 2002-2009.

- ↑ Bredekamp, Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil; id., Schlussvortrag.

- ↑ Interview of Horst Bredekamp and Ulrich Raulff, in: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 05/28/2004: „Wir sind befremdete Komplizen“; see Horst Bredekamp, Marks and Signs. Mutmaßungen zum jüngsten Bilderkrieg, in: Peter Berz/Annette Bitsch/Bernhard Siegert (eds.), FAKtisch. Festschrift für Friedrich Kittler zum 60. Geburtstag, München 2003: 163-169.

- ↑ See the articles by Frank Kämpfer, Iris Wigger, Hanno Loewy, Gerhard Paul, Cord Pagenstecher in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, 2 Volumes.

- ↑ See Silke Wenk, „Die Wehrmacht“. „Arische“ Männlichkeit in der Skulptur von Arno Breker, id., Bildatlas I: 558-565.

- ↑ See f.ex. on National-Socialism before 1933: Gerhard Paul, Aufstand der Bilder. Die NS-Propaganda vor 1933, Bonn 21991, as well as for the time after 1933: Markus Urban, Die Konsensfabrik. Funktion und Wahrnehmung der NS-Reichsparteitage, 1933-1941, Göttingen 2007; in contrast from a cultural science perspective: Paula Diehl, Reichsparteitag. Der Massenkörper als visuelles Versprechen der „Volksgemeinschaft“, in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Bildatlas I: 470-479.

- ↑ See numerous examples in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder.

- ↑ Thomas F. Schneider: „Im Westen nichts Neues“. Ein Film als visuelle Provokation, in: id., Bildatlas I: 364-371; Hannes Heer, Bildbruch. Die visuelle Provokation der ersten Wehrmachtsausstellung, in: id., Bildatlas II: 638-645.

- ↑ See f.ex. the articles by Kai Artinger, Susanne Popp, Gerhard Paul, Astrid Wenger-Deilmann in: id., Bildatlas I, as well as by Petra Maria Schulz, Ästhetisierung von Gewalt in der Weimarer Republik, Münster 2004; Cornelia Brink, Bilder vom Feind. Das Scheitern der „visuellen Entnazifizierung“ 1945, in: Sven Kramer (ed.), Die Shoah im Bild, München 2003: 51-69.

- ↑ From an art history perspective see Georges Didi-Huberman, Bilder trotz allem, München 2007; with a slightly different focus Miriam Yegane Arani, Holocaust. Die Fotografien des „Sonderkommando Auschwitz“, in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Bildatlas I,: 658-665.

- ↑ Bredekamp, Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil: 57.

- ↑ Gerhard Paul, Der „Kapuzenmann“. Eine globale Ikone des beginnenden 21. Jahrhunderts, in: Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Bildatlas II:. 702-709; Sabine Schiffer/Xenia Gleißner, Das Bild des Propheten. Der Streit um die Mohammed-Karikaturen, in: id.: 750-760.

- ↑ Interview of Horst Bredekamp and Ulrich Raulff; also see the interview of Arno Widmann with Horst Bredekamp „Neu ist, Menschen werden getötet, damit sie zu Bildern werden“, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 01/05/2009; similarly from a visual culture studies perspective: Nicholas Mirzoeff, Von Bildern und Helden. Sichtbarkeit im Krieg der Bilder, in: Lydia Haustein/Bernd M. Scherer/Martin Hager (eds.), Feindbilder. Ideologien und visuelle Strategien der Kulturen, Göttingen 2007: 135-156; from a historical studies perspective: Gerhard Paul, Der „Pictorial Turn“ des Krieges. Zur Rolle der Bilder im Golfkrieg von 1991 und im Irakkrieg von 2003, in: Barbara Korte/Horst Tonn (eds.), Kriegskorrespondenten. Deutungsinstanzen in der Mediengesellschaft, Wiesbaden 2007: 113-136.

- ↑ Gerhard Jagschitz, Visual History, in: Das audiovisuelle Archiv 29/30 (1991): 23-51.

- ↑ On the criticism of the five volumes edited by Edgar Wolfrum „Deutschland im Fokus”, Darmstadt 2006-2008, see the review by Andreas Schneider, Rezension zu: Wolfrum, Edgar: Die 50er Jahre. Kalter Krieg und Wirtschaftswunder, Darmstadt 2006, in: H-Soz-u-Kult, 08/30/2007, http://www.hsozkult.geschichte.hu-berlin.de/rezensionen/2007-3-158.

- ↑ Paul (ed.), Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, 2 Volumes.