Publikationsserver des Leibniz-Zentrums für

Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam

e.V.

Archiv-Version

Living History (english version)

Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 20.04.2021 https://docupedia.de/tomann_living_history_v1_en_2021

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2181

Living history is a permanent fixture of our day-to-day world. On almost any given weekend, people can attend medieval reenactments at markets and castles throughout Germany. City tourists take part in historical tours conducted by guides dressed as medieval damsels or other historical-looking figures who offer an introduction to local history. This approach to history as an entertaining, lively, interactive and hands-on experience is often accompanied by place branding and attempts to make a certain destination more attractive to potential tourists. But this is only one of the many ways the multifaceted term living history is used.

Living history encompasses a broad semantic range. To date there is no clear definition of these often playful, performative-sensory and affective forms and practices of bringing to life and appropriating the past. The German-speaking world in particular has pointed out the semantic ambiguity of the term, not to mention the fact that it’s an oxymoron or epistemologically problematic. To many Germans, scholars included, living history[1] seems to be an “unreal process of reviving the past.”[2] Wolfgang Hochbruck, an expert in American studies, even refers to living history as a “semantic swamp”[3] in need of draining before any in-depth discussion can take place regarding its characteristics and qualities. The director of the German Historical Institute in Washington, D.C., Simone Lässig, on the other hand, understands living history as “in equal measure a movement, a philosophy, an educational tool, and a special technique for presenting and communicating history in museum contexts.”[4] Canadian historian David Dean also has no problem defining living history, which he describes as “both a movement and a practice,” its purpose being “to simulate how lives were lived in the past by reenacting them in the present.”[5]

Living history, moreover, is closely linked with the term public history. Both terms describe historical representations in the public sphere, though public history is more broadly defined than the performative-sensory practices of appropriating the past characteristic of living history and expressed, for instance, in the form of museum work or reenactments. Unlike living history, public history is not only used as a generic term for the varied non-academic approaches to dealing with the past but is also understood as a subdiscipline of historiography. Irmgard Zündorf defines it as follows:

“Public history on the one hand comprises every form of public representation of history that is aimed at a broad, non-specialist public with no historical training while on the other hand entailing the historical investigation of the same. It responds to the increasing interest in history in purely quantitative terms as well as to the qualitative change in the standards of historical narrative.”[6]

As an “agency of reflection and mediation between research and public interest,”[7] public history develops methods and terminology for analyzing public representations of history and trains historians to work in and with a more broadly defined public. In this sense, the phenomena of living history are a subject of the public history that researches them.

The collective term “living history” in its various definitions, forms and manifestations will be spelled out in the following, thereby providing an overview of this widespread phenomenon. Developments in the United States and Europe will be taken into consideration, as well as taking a look at the historical precursors of present-day forms. The living-history approach is particularly relevant in open-air museums, which will be discussed in detail below. Whereas living history in the Anglo-American world has long been a well-established feature of the educational and cultural work of museums, at German institutions there is still a great deal of skepticism towards this form of historical representation despite the successful implementation of various living-history programs. The concept of living history and its evolution will be introduced here using two examples of large living-history museums in America. Finally, the overview ends with the question how the fields of history and cultural studies might best engage with living history and which theoretical approaches exist for investigating and analyzing living history.

Definitions, Forms and Manifestations of Living History

It is clear from the discussion above that there is no generally accepted definition of living history. This is due both to the dynamic growth of living history in its varied forms as well as to the many terms that attempt to frame these phenomena theoretically. Archeologists and anthropologists sometimes use the term “time travel” to describe the various forms and methods of reenacting and reliving the past outside an academic context.[8] Theater, cultural and performance studies as well as art and art history all use the term reenactment.

The term “histotainment” is often used if the focus is on commercial aspects or the relationship between historical education and entertainment.[9] Living history also shows considerable overlap with bodily practices of memory and history culture.[10] The newest trend in cultural studies is the term “doing history” to describe everyday cultural practices that place special emphasis on actively engaging in the appropriation of the past through physical experience and sensory perception. This overlaps in large part with the core elements of living history.[11]

As a broadly defined and semantically ambiguous umbrella term, living history encompasses much of the abovementioned terminology.[12] It has established itself internationally in the last three decades in various institutional configurations, museums in particular, as well as among lay and hobby historians.

The English terms living history and reenactment are often used synonymously by German-language scholars for lack of a coherent and generally accepted distinction.[13] The present article acknowledges this tendency, addressing both living history and reenactment along with the respective forms and practices they refer to. The following section will attempt to define the two terms more clearly.

Jay Anderson and the Origins of Living History

The lack of clarity about what living history refers to and encompasses has been a constant feature of discussion ever since the term was coined more than thirty years ago. Classifying the concept in terms of conceptual history might therefore prove useful. One of the first attempts to lend the field a structural underpinning dates back to 1984, when American scholar Jay Anderson defined living history as a collective term. Anderson taught in the Folklore and Museum Studies department of Western Kentucky University and was active himself in all the areas of living history he defined. In his book Time Machines: The World of Living History he describes them as “an attempt by people to simulate life in another time. Generally, the other time is in the past and specific reason is given for making the attempt to live as other people once did.”[14]

The specific reasons he indicates are “research, interpretation and play,”[15] an extremely diverse set of motivations which he sees linked to experimental archeology, the living-history performances at museums and historic sites, as well as to lay people engaging in history as a hobby in their free time. The difficulties of defining the term so broadly are obvious, and yet scholars still routinely make reference to Anderson’s first comprehensive definition, if only to critically distance themselves from it. Despite the many criticisms, Anderson’s attempt at a wide-ranging definition of living history is a milestone in conceptual history, one which has had a formative influence on our understanding of the term and the discussions around it. The imprecision – or openness – that Anderson attributed to living history is still the case today.

Scholars are most critical of Anderson’s inclusion of experimental archeology in the purview of living history. As a specialized field of archeology, it utilizes experimental methods in an effort to gain new insights into pre- and early historical phenomena that are only partially accessible to us in the form of material sources or in order to come to conclusions beyond what can be reasonably inferred from the analysis of archeological finds. “Experimental archaeology is conceived of as a method of interpretation that gives meaning to the archaeological record.”[16]

The experiments are scientific in nature. They serve to increase knowledge, are documented and should be repeatable under similar circumstances. The aim of experimentation is to develop propositions or hypotheses that can then be tested.[17] The repertoire is extensive and ranges from building replicas of Stone Age ovens and baking bread in them to constructing earthen embankments in order study how they change over time.[18] Experimental archeology is usually distinguished from other areas of living history on the basis of its being a scholarly endeavor with particular research interests, which naturally entails a different methodology than the forms of living history found in museums or pop culture.[19]

The didactic moment of conveying knowledge is the key aspect of historical interpretation as defined by Anderson, which mainly involves personalized and emotionalized performances in living-history museums. Living history is understood here as bringing life into the “dead” material objects of museums by means of specially trained, costumed individuals performing in accordance with a didactic concept. Anderson’s vision of a living-history museum came close to being a comprehensive mock-up of lived-in historical worlds, following the prototype of the walk-in, true-to-scale diorama that would enable the visitor to experience what life was like in the past.

First- or third-person interpretative approaches have usually been used to this end. The interpreter using the third-person mode talks about past individuals from an outside, historical perspective (“They did this…”). There is a clear remove from the historical period being reenacted. The interpreters can act as moderators who accompany museum visitors and answer any questions they might have. This marked distance to the past encourages visitors to make observations about how people lived in the past as well as to view the present with a more critical eye.

Interpreters employing the first-person mode present themselves to visitors as fictional characters from the past, they seem to speak in an old-fashioned way, and try to draw visitors into the historical world they purport to live in (“We do this…”). The interpreters often use dialogue as an educational tool to make their presentations more lively and encourage visitors to participate. Visitors are treated as contemporaries and not as figures from the future. This helps them immerse themselves in the experience and block out any references to their present-day lives.

The interpreters pretend to not know anything outside the lifespan of the character they are representing. They refuse to acknowledge any contradictions from the present, this immersive approach being an attempt to stimulate the imagination of museum visitors and give them the feeling of being witnesses to day-to-day life in a bygone era. The communicative strategy of adopting a whole persona is predicated on an exact study of the life and world of these fictional alter egos and obviously has its limits in the case of scant or nonexistent biographical sources, especially for the distant past such as pre- and early history or even the Middle Ages.[20]

There is also a second-person approach, in which the museum visitors themselves are the center of attention, e.g., trying out historical weapons or making food under historically authentic conditions.[21] The visitors in this participative form engage in a more self-directed and self-experiential learning process, one which nevertheless has its limits, as the experience is only partly self-directed, occurring under the guidance of museum employees and following a predetermined script.[22]

Simulated history for purely recreational purposes is the domain of so-called history buffs, i.e., groups of people with no institutional affiliation who dedicate themselves to historical themes in their free time. History buffs, in Anderson’s view, are mainly (male) hobby historians and collectors interested in the active (re)appropriation of history and who turn to historical topics for personal reasons, “often for play and the joy of getting away.” Reenactors is the generally accepted term for these individuals nowadays. They are loosely organized, sometimes in societies, and reenact concrete historical events using faithful reproductions of period gear and uniforms, simulating combat formations at historical battle sites, e.g., the Battle of Gettysburg (1863) in the American Civil War. Events from contemporary history, especially World War II, are also reenacted – notably not in Germany, but in neighboring countries like Poland, the Czech Republic and Belgium, as well as in Britain and the United States.[23] A huge, international scene has developed for World War I reenactments – again with the exception of Germany, where there is considerable reluctance to reenact events of the twentieth century in general.[24]

![U.S. Navy troops reenacting the D-Day invasion in Normandy on the 75th anniversary of the event. Photo: Michael McNabb, June 7, 2019. Source: Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa/U.S. 6th Fleet / [https://www.flickr.com/photos/94966166@N02/48023249368 Flickr] public domain](sites/default/files/import_images/6033.jpg)

Since reenactments mostly take place outside the established and authoritative context of museums, the participants are particularly keen on the authenticity[25] of location, performance and equipment. Their understanding of authenticity is a very specific one.[26] By striving for historical accuracy in approximating the original, reenactments immerse participants in a slice of the past, the experience making this past more relatable and possibly even providing a “period rush” or “magic moment.”[27] The performing subject, in other words, can better empathize with historical experiences by undergoing the experience themselves. Playful iteration and subjective experience temporarily dissolve the gap between the past and the present.[28] Reenactors, in their self-perception, often wish to inform and educate the public at the same time. Reenacting a historical event in such a way that it becomes an unforgettable experience for spectators is a key aim of participants – especially when reenacting events they consider under- or misrepresented in the official textbook narratives of history.[29]

The literature to date has pointed out the considerable motivational and socially cohesive power of historical reenactments. Reenactments dissolve hierarchies in the here and now, lending their participants the feeling of community as part of individual reenactment groups as well as in the reenactment scene in general.[30] Others argue that reenactments, with their similarity to war games and their idealization of warlike male attributes, are a reaction to the current crisis of manhood.[31] Scholars also see escapism as a motivation to participate in reenactments, the latter being perceived as a refuge and antidote to the dislocations of modern life, to globalization, technology overload, as well as to the fast pace of everyday life.[32] Ethnological research also sheds some light on the phenomenon, recognizing the motives of “self-awareness and self-placement,” reenactments offering the possibility of “borderline experiences” as well as providing “new modes of action and experience.”[33]

Recent Developments in Living History

Anderson’s typology offers an initial overview of the phenomena he subsumed under the collective term living history. Since Anderson’s groundbreaking work, the practice of performing and appropriating the past has undergone a vigorous development. More recent literature on the topic of living history, among others the standard German-language overview Geschichtstheater (Historical Theater)[34] published in 2013, includes “live action role-playing games” (LARP). LARP is similar to reenactment in that it also entails characters playing a part, but is less concerned with historical events and their accurate simulation. LARP creates fantasy worlds by means of role play that is sometimes suggestive of historical events but does not necessarily have a historical orientation. LARP conventions rarely aim to communicate historical knowledge. They follow a preconceived narrative framework and participants tend to shun an audience, since they merely want to enjoy the pleasures of fantasy and fictional role play. A more recent development is “reenalarpment,” combining elements of reenactment and LARP. It differs from conventional LARP in that it is set in a concrete historical era and minimizes elements of fiction and fantasy.

The literature likewise treats the reality-TV docusoap as a form of living history and historical reenactment.[35] The format has massively increased in popularity in Europe, the United States and Australia since the early 2000s. The principle is the same everywhere. A preselected group of people is filmed in an artificially constructed historical situation and setting as they carry on with their day-to-day lives. Its appeal as opposed to the purely fictional series is the different sense of reality offered by amateur actors playing “real people.”[36] In the case of Schwarzwaldhaus 1902 (Black Forest House, 1902), a well-known miniseries produced by SWR (Southwest Broadcasting), the actors were a family from Berlin who temporarily opted out of modern life and its creature comforts to get a sense of what life was like on a small German farm a century ago. The broadcaster described the format as an “experiment” intended to provide a deeper understanding of the past and the present.[37]

The show was hardly a rigorous scientific experiment, the television format generally giving priority to the drama and entertainment aspects of the show.[38] Its protagonists “traveled back in time” to give their viewing public a glimpse of what it might have been like to live in the past. It is obvious that this is actually impossible. The amateur actors are performing in an artificially constructed reality that at best merely confirms their own assumptions about the past, authenticating these assumptions by way of personal experience but hardly generating any real insight.[39]

Simply put, the protagonists cannot just divest themselves of their link to a present that determines their feeling, thinking and behavior even if these are staged against a historical backdrop. The day-to-day problems posed by a supposedly historical environment are ultimately ahistorical. Modern processes of socialization in a technological world give rise to problems and ways of thinking that would have been completely alien to our ancestors.[40]

Whereas living history and reenactment largely overlap in practice, the terms often being used synonymously by scholars, a clear distinction is made between them in the field of art and art history. Iterative strategies and references to the past are generally referred to here as reenactments. These are a marginal phenomenon from the perspective of living history, but are still worth including in this overview, in particular the artistic practices of historical emobodiment and repetition. Reenactment in the arts was booming in the 1990s and 2000s, which theorists tended to view as part of an ongoing engagement with the question of originals vs. copies rather than presenting a wholly new phenomenon.[41] Artistic reenactments such as Marina Abramović’s Seven Easy Pieces, a series of performances on seven consecutive nights at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, are mainly interested in the character of these performances per se and less so in the historical context of previous performances. By reenacting older performances and documenting them, as it were, Abramović questioned the ephemeral as a defining feature of performance art.

Numerous art performances, however, have a clear historical orientation – the works of Polish artist Rafał Betlejewski, for example. In his 2010 project “The Barn is Burning,” he commemorated the 1941 massacre of Polish Jews in Jedwabne, addressing the highly controversial topic of Poland’s complicity in the Holocaust. Though the happening did not take place at the original site of the pogrom, it was spectacular nonetheless. Betlejewski set fire to a barn doused with gasoline and escaped from inside the burning structure. Rather than the mimetic reenactment of the past, his intent was to provoke, an essential characteristic of many such artistic reenactments. In contrast to classic reenactments with their striving for accurate, authentic representation, artistic reenactments often purposely deviate from the historical record, using creative license to call attention to the impossibility of authentic reproduction.[42]

Video games with historical settings are a similar marginal phenomenon. The term reenactment is used here for the purpose of discussing whether the experience of computer gaming can be defined as reenactment at all. The playful reenactment of the past, interpretation and role-playing in particular, was shown above to be a core aspect of living history. Historian Brian Rejack expressed his doubts in 2007 as to whether historical video games constituted reenactment in this sense, as “bodily engagement, which lends reenactment its form of experiential epistemology, is absent from gaming.”[43] Video games, he argued, were more about the visual representation of the past.

But the features of this type of gaming have fundamentally changed in the past decade. The creation of historical worlds as a narrative framework has been opened to whole new possibilities through augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR). The relationship between humans and machines as well as between players and characters is consequently changing with it. If players used to sit in front of the screen, navigating figures through historical-looking game worlds, the experience and reenactment of an assumed historical reality has now attained maximum immersion. The players themselves, materialized in a computerized historical game world, have now become active protagonists. The bodies and minds of players are translated “onto the screen through algorithmic avatars.” These “forms of incorporation” are achieved by “identifying with the character or through actions or the possibilities of action.”[44]

Unlike other forms of living history, computer games are characterized by their shared authorship. The narratives that take shape during the course of the game are based on the decisions of the game developers as well as the actions of the players, the performative potential and agency of the latter being largely circumscribed by the former, however. Though video games with a historical setting lack any direct physical interaction with historical materials and the simulation of bygone worlds is structured around the gaming logic of winning and losing, they are nonetheless treated by some as forms of historical reenactment.[45]

This overview makes clear that living history is a collective or umbrella term gathering a wide range of practices and modes of imagining, appropriating and performing the past. There is no universal definition, the term itself developing along with the ever growing variety of phenomena. But it is possible to identify some general, overarching criteria of living history. In doing so I will use a more narrow interpretation of Jay Anderson’s originally rather broad definition and leave aside experimental archeology with its scientific claims.

Living history primarily revolves around the activity and behavior of subjects outside the confines of academia and its production of historical knowledge.[46] The construction of historical meaning occurs in the moment of activity. The resultant creation of meaning indicates both the performative quality of living history as well as its experiential character. The performativity of living history is essentially theatrical and emphasizes the processual nature of meaning creation.[47] In the context of museums, the theater of living history is meant to enable participants to “absorb history rationally and emotionally in equal measure – that is to say, with the mind and the senses.”[48]

This overview also shows that the terms living history and reenactment exhibit extensive overlaps in theory and practice and cannot be neatly differentiated. Anderson’s proposed definition of living history construed it as a collective term for the performative-sensory, iterative approach to the past and made reenactment a subcategory of this. But our understanding of the term reenactment has expanded and shifted considerably since then. It now extends beyond amateur events with their seemingly mimetic and affirmative approaches to include a range of popular practices of performative appropriation, from the visual arts to computer games. In academia, reenactments are increasingly considered to be a “reflective artistic or scholarly procedure”[49] that is experimental in nature and transcends the text-based discursive production of knowledge. An expression of this new understanding of reenactment as both a performative-sensory, iterative practice of appropriating the past and as an experimental procedure transcending the text-based production of knowledge is the Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies.[50] The handbook not only outlines various theoretical approaches but also references the burgeoning academic discipline of reenactment studies to underscore the significance of reenactments in cultural practice and theoretical debates.

Historical Predecessors and Subsequent Developments

Living history is not an exclusively postmodern phenomenon that emerged in the late twentieth century. Its varied forms of expression reflect its diverse historical roots, originating mainly in a museum context but also outside of it. Living history is rooted in religious passion plays and later in the historical processions popular in the nineteenth century. Cities, villages or groups of costumed individuals reenacted the past in the form of public street parades with the aim of strengthening community spirit by referring to a shared past.[51]

Similar to the tableaux vivants (“living pictures”) popularized in the late eighteenth century – a series of often elaborately staged but static representations of historical paintings, scenes or suchlike – the pageants popular in the late nineteenth century used local amateur actors to reenact meticulously choreographed historical scenes. Common in Great Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia, pageants were an opportunity to participate in and experience local or regional identities. They were a kind of secular procession with festival character that aimed to pass down these identities and allegiances or to celebrate the “past as a harbinger of the present.”[52]

One of the first and most famous was Louis Napoleon Parker’s (1852-1944) Sherbourne Pageant in Dorset, England, originally performed in 1905 to mark 1,200 years since the town’s founding. Parker’s pageant, with around 900 locals, all amateur actors, rehearsing scenes from the town’s history for weeks in advance and performing them publicly against a historic backdrop, became a model for communities and towns worldwide.[53] Pageants were big historical events with participants from all walks of society offering performances of local history that were meant to bolster a sense of community weakened in the wake of industrialization, urbanization and individualization.[54]

![''Sherbourne Pageant'', Dorset 1905. The picture is taken from the film catalogue of the Charles Urban Trading Company (1906). Source: Luke McKernan / [https://www.flickr.com/photos/33718942@N07/27421189244/in/photolist-HM7Tv8-JHnytt-HM7LdU-HM7TvD-HM7Lid/ Luke McKernan / Flickr], License: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/ CC BY-SA 2.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/6032.jpg)

Artur Hazelius and the Skansen Open-Air Museum

The origins of living history in a museum context go back to the world’s first open-air museum, founded in Stockholm in 1891 by Artur Hazelius (1833-1901). Though the Skansen museum was the first of its type, many of its exhibition techniques had been employed elsewhere before – at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair, for instance, parts of which were laid out as an ethnographic park displaying replicas of national architecture as well as costumes and traditions of the participating countries. Precursors of the Skansen museum were also found in neighboring Norway, where buildings were being relocated to a royal estate in Bygdøy in the early 1880s to preserve them and make them accessible to the public. Hazelius visited Bygdøy in 1884 and was evidently inspired by it.[55]

Artur Hazelius, who viewed himself as a “social improver, reformer and folk educator,”[56] wanted to create a museum dedicated to the daily life of his fellow Swedes. With the country’s major museums hitherto focusing on art or archeological finds mostly from foreign civilizations, Hazelius wanted to shift the focus to the day-to-day lives of normal people, rich and poor. To this end he had buildings from all over Sweden transported to the museum grounds in Stockholm in order to convey a vivid impression of life in preindustrial Sweden with its mixture of nature and culture. Skansen, in Hazelius’s nationalist-romantic vision, was intended to arouse patriotic feelings in its visitors and strengthen their national consciousness. The newfangled form of an open-air museum in an attractive park setting with long opening hours and its combination of culture and entertainment was consciously meant to appeal to the widest possible audience.

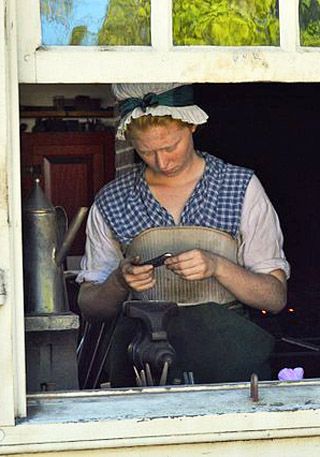

Hazelius’s objective was to create a living museum where visitors could see a “Sweden in miniature”[57] and encounter the inhabitants of the buildings on display. His museum was not an assemblage of neatly arranged exhibits but was supposed to have “living characteristics,” initially in the form of life-size figures set up in the buildings, which were later replaced with museum employees demonstrating various trades and crafts.[58] Swedish art historian and museologist Sten Rentzhog sees a clear connection between Skansen and the subsequent development of living history: “When the concept ‘living history’ was brought into use much later, out in America, people had no idea how close they came to Artur Hazelius.”[59]

Living history as a means of representing the past was particularly successful in the United States after World War II. Both the concept and practice of living history became prevalent there in the 1970s, mostly in the context of open-air museums.[60] The fact that many museums were private rather than state-funded and had to generate an income to stay afloat was a contributing factor to the emergence and establishment of living-history museums. Participant-oriented museum work is much less determined by the interests of curators and researchers. Moreover, according to Simone Lässig, North American museums were often founded with the very aim of “serving a less educated public.”[61]

German museums developed differently. Enlightenment ideals of education began transforming formerly private and elite curiosity cabinets into public educational institutions in the eighteenth century. Select artifacts and relics of past events and processes, which became “museum objects” by dint of their being selected and isolated from their original contexts, were exhibited in a relatively static form, usually with an educational aim. And it is still the primary objective of most German museums to present valuable objects to an educated and inquisitive public.[62] Though this educational mandate has surely changed over time, it might help explain the skepticism towards living history among German museum-makers.

North American living-history museums, by contrast, endeavor to have a wide appeal and to put objects, people, events and places in historical context by means of “live interpretations.” The standard museum repertoire of exhibits, artifacts or faithful reconstructions accompanied by explanatory texts was effectively expanded by living history, which relies more on emotions as the primary museum experience. Museum objects, especially historical originals, were thus relegated to the sidelines, as they stood in the way of the concept of living history, of making history come alive rather than presenting inanimate objects. The focus on daily life and the lived-in worlds of the lower or marginalized classes replaced the notion of the history of events, and this with a dual aim: “Visitors should literally get a hands-on experience of history in order to really grasp it.”[63] This concept was innovative in the 1970s and lent new popularity to many historic sites in the United States.[64] The developments of that period were defining for the forms of living history characteristic of today’s museums.

Plimoth Plantation and Colonial Williamsburg as Trailblazers

The two most prominent examples of living-history museums in the United States, which also played a pioneering role in establishing it as a popular form of representing the historical past, are Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts and Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia. Both museums are located on the East Coast and focus on presenting key moments of early American history and nation-building.

Plimoth Plantation is dedicated to the arrival of the early Puritan settlers in North America, who sailed across the Atlantic on the Mayflower and founded Plymouth in the 1620s. It began its operations in 1948 with the erection of the first Pilgrim house on the site of the former settlement. An entire Pilgrim village was set up in 1959 and peopled with wax figures in the 1960s to give the village a lively impression and simulate the lifeways of the Pilgrim Fathers. The wax figures were eventually replaced by costumed interpreters in 1969 and the living-history concept introduced. Towards the late 1970s the interpreters began to adopt the roles of individual settlers and speak in historical dialect, paving the way for first-person interpretation and a “totally recreated ‘living’ environment.”[65] In this manner Plimoth Plantation took an important step towards the museum performance, enabling visitors to enter a space in a seemingly different historical period utterly divorced from its surroundings.[66]

![Plimoth Plantation, Plymouth, Mass., May 2005. Photo: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Muns Muns], Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plimoth_Plantation.JPG Wikimedia Commons], License: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en CC BY-SA 2.0]](sites/default/files/import_images/6027.jpg)

But even before the implementation of this first-person mode of interpretation open-air museums such as in Colonial Williamsburg were utilizing a form of presentation with costumed employees in or outside historic buildings. In the 1920s and 1930s, on the initiative of local pastor William Goodwin and with the generous financial assistance of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., the historic center of Williamsburg, the eighteenth-century capital of the Colony of Virginia founded by English settlers, was slowly transformed into an open-air museum.[67] The aim was the faithful reconstruction of the settlement as it existed in the eighteenth century. All modern influences were to vanish from the historical center of town, with newer buildings either being torn down or relocated, and businesses on the main street being moved to a new commercial and shopping district at the edge of the historic area.[68] The result of these reconstruction efforts was a new historic town center that now forms the core of the Colonial Williamsburg open-air museum, a historic area located in the present-day city of Williamsburg.[69]

Whereas Plimoth Plantation had no material remains to fall back on during its reconstruction, Colonial Williamsburg is an often inseparable mixture of old and new, the location and structure of newly built sections being based on the meticulous study of archeological and archival material as well as surviving maps. Though the focus of reconstruction during the 1930s and 1940s was reverting the town to its eighteenth-century state, costumed interpreters were part of the Colonial Williamsburg concept starting as early as 1934. Handicraft demonstrations became a permanent fixture in 1937, using both third- and first-person modes of interpretation as the years wore on. Since the early 2000s the focus has shifted to the performance of rehearsed scenes and the impersonation by professional actors of historical figures such as George and Martha Washington. The scenes follow scripts with fictional interpretations of historical events in Williamsburg. Fact and fiction are intermingled.[70]

![A professional actor impersonates Thomas Jefferson giving a speech on the grounds of the Governor’s Palace in Colonial Williamsburg. Photo: Larry Pieniazek, Colonial Williamsburg, April 3, 2006. Source: [https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colonial_Williamsburg_Thomas_Jefferson_Reenactment_DSCN7269.JPG Wikimedia Commons], License: [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en CC BY 2.5]](sites/default/files/import_images/6029.jpg)

The establishment of living history during the 1970s occurred in a period of transition in which the representation of the past was being questioned and renegotiated in American museums (and elsewhere). Under the influence of the civil-rights movement and New Social History, many criticized the prevailing focus on the history of political events and historical elites. The “celebratory history” of Colonial Williamsburg hitherto practiced with patriotic pathos was now being supplemented by depictions of the middle class as well as the black population. The first black interpreters appeared in 1979, thus integrating slavery in the presentations and establishing an African American interpretation as part of the museum village.[71] The living-history approach with its focus on the history of everyday life lent itself to the portrayal of historical worlds and the demand for a “democratic presentation of history in museums based on a broader concept of culture.”[72]

This shift was particularly drastic at Plimoth Plantation. Whereas Colonial Williamsburg still gives a “highly polished” impression,[73] Plimoth Plantation is downright grubby by comparison. Small animals roam the streets and the buildings themselves are dark and dirty. This reflects a conscious decision of the museum management, which in 1969 declared its intention to dismantle and correct with the aid of scholars the myth of the Pilgrim Fathers, the historic sites themselves, it felt, having contributed to their idealization. An “objective depiction of the real culture of the Plymouth colonists”[74] would help to faithfully reconstruct the daily lives of the Puritans, thus counteracting the Pilgrim myth.

This “living history metamorphosis”[75] resulted in traditional captions disappearing from the museum village almost overnight, while the stereotypical costumes once worn by employees were now replaced with historically accurate attire. Under director James Deetz, museum employees began to live and work with the historical objects they presented, using them to carry out everyday tasks and hence give an authentic impression of the year 1627. This meant confronting visitors with a competing narrative of the American national myth. On the outskirts of the plantation is Hobbamock’s Homesite, the reconstruction of an indigenous Wampanoag village. The conflict-ridden history of the colonization of America is presented there in third-person interpretation, an intentional break, for conceptual reasons, with the museum’s first-person mode of interpretation. The natives demonstrate age-old local traditions while questioning conventional colonial historiography from a more contemporary perspective.

The Discourse on Living History in the German-Speaking World

Despite its European origins, the concept of living history has been most successful in the United States, being deeply anchored nowadays in the self-understanding of many open-air museums there. The concept is less established in the German museum industry.[76] The different development and self-understanding of German and American museums has been alluded to above. While a number of open-air museums were founded in Germany in the early twentieth century – the Ammerland Farmhouse in Bad Zwischenahn, for example, which sought to preserve traditional, preindustrial ways of life while likewise having a certain entertainment value, complete with concession stands and an accompanying costume festival (Trachtenfest) in order to appeal to the broadest possible audience – there were no demonstrations of farm work or rural handicrafts, and no historically dressed interpreters like the ones at Skansen in Sweden.

The open-air museums founded in the postwar era for the most part continued the tradition of presenting buildings in an uninhabited state. The director of the Rhenish Open Air Museum in Kommern, Adelhart Zippelius (1916-2014), focused on the material culture of the agrarian world, made accessible to the visitor mainly as an intellectual experience rather than bringing it to life.[77] While there were some initial attempts at museum theater in German museums during the 1970s,[78] museum-makers were wary of too much living history, which they feared might lead to the banalization of content and objects. They thus tried to draw a line between the institution of museums and other non-museum recreational facilities.[79]

But this has changed since the 1990s, with elements of living history being introduced, e.g., at the Franconian Open Air Museum in Bad Windsheim, the Kommern Open Air Museum, and the Kiekeberg Open Air Museum. Museums that lack their own living-history program often involve reenactment groups in their work. Alongside many successful cooperative ventures of this sort, there have also been unfortunate instances of reenactors displaying problematic political views, resulting in distorted representations of the past especially with regard to early history. The Ulfhednar group is one of the most prominent examples of how representations of Germanic tribes have sometimes been combined with dubious political symbols, the group having displayed swastikas in renowned German museums contrary to all archeological evidence.[80]

Another reason for the widespread misgivings and skepticism towards living history in Germany might be due to practices dating from the Nazi era. Numerous open-air museums incorporating elements of living history and reenactment were set up in Germany after 1933, all dedicated to “Germanophile ‘national education’” in line with Nazi ideology.[81]

Two publications from 2008 reveal that living history in German museums is still a subject of critical debate.[82] On the one hand, there is an emphasis on the “considerable historical power” of living history, which strengthens visitors’ understanding of historical processes and structures thanks to its emotional appeal and its “bringing to life the culture of dead objects.”[83] Others point out that living history is an effective marketing instrument, bolstering attendance and media coverage. This gives rises to concerns, however, that the optimization of museum operations will take precedence over the institution’s core mission.

Skeptics, on the other hand, are fundamentally concerned about the museum experience being turned into an event that is focused on entertainment and attempts to simulate historical reality at the expense of a more critical, reflective approach. The educational mandate of museums, it seems to them, is incompatible with the premise of event-oriented representation. Moreover, from a learning-theory perspective there are concerns about a lack of transparency when visitors are confronted with representations of supposedly authentic historical situations that are in fact merely constructs. These critics therefore suggest providing additional tools to encourage a more detached reflection, interpretation and deconstruction of said representations.[84] The aforementioned misgivings primarily apply to the first-person mode of interpretation, which consciously excludes the present and any references to the modern-day world of visitors. If the first-person interpreter is asked a question in a museum, he or she needs to be able to provide the necessary information as if this person were a “contemporary witness.” Gaps in research, a lack of documentation from the period he or she is representing, and the fragile process of historical inquiry cannot be articulated, since the interpreter has to pose as a living source.[85]

Wolfgang Hochbruck tries to allay these fears at a semantic level with the suggestion that we simply refer to living history as a kind of historical or museum theater. Viewed as a form of theater, living history would not make the grand claim of reconstructing irreproducible bygone worlds and experiences of the past, but would be thought of as performances that are limited in time, space and content.[86] Markus Walz makes a similar suggestion to use the term “history spectacle [Spiel].” Facts and situations from the past are then taken up for the purpose of individual exploration and/or appropriation or to portray and communicate them to others.[87]

Certain aspects of this discussion seem obsolete in light of more recent developments. Museums have begun to react to new challenges in the form of user-generated content and individually curated content online. Their experimental, participative or digital educational offerings exhibit elements of living history which, thanks to their focus on immersion and the emotional link between the past and the present-day lives of visitors, make them competitive in the age of Museum 2.0. This form of individual experience shares characteristics of reenactment when, for instance, visitors at a museum adopt their own roles, hence individualizing the learning experience and the creation of historical meaning.[88]

Living History as a Subject of Scholarship

A variety of academic disciplines have investigated the phenomena of living history, and yet there is no uniform terminology and no established set of research tools. The various disciplines have approached the phenomenon with different theoretical premises, leading to diverging assessments, e.g., as regards its potential from an epistemological or learning-theory perspective. Matters are complicated even more by the abovementioned overlap in the definitions and usages of the terms living history and reenactment. There is currently a trend, however, to use the term reenactment in discussing theoretical implications in particular, e.g., the epistemological potential of practices for envisioning and appropriating the past.

Added to this are theoretical considerations from the field of cultural and media studies that posit the human body as a place of learning and a starting point for alternative strategies of knowledge production regarding the past. Reenactment is then understood as “a body-based discourse in which the past is reanimated through physical and psychological experience.”[89] This embodiment is a multisensory form of perception and physical experience that uses the body as an explorative tool[90] in order to make the past more tangible. Its experience-based argumentation questions the relationship between experiential ways of acquiring knowledge and a discourse-oriented, text-based scholarship, and hence the relationship between institutionalized scholarship and non-academic, alternative forms of knowledge production in the “amateur” domain.[91]

Yet another approach to understanding reenactment and living history apart from the body as an explorative tool is the materiality of the objects that constitute them. Things, objects and artefacts are key to the specific experience of linking the past to the present. Material culture Studies combines a variety of approaches to explore the importance of objects in the functioning of living history and reenactments, including the “actor-network theory” of Bruno Latour, the “more-than-representational theory” of Hayden Lorimer, and the “cultural biography of things” of Igor Kopytoff.[92]

Performance studies is also a common approach to investigating reenactment and living history. Here, apart from corporeality, the focus is on the theatrical, the staged nature of both, pointing to the processual and inventive aspect of meaning creation: “The reenacting body can function as a mode of historical inquiry and representation, exploring and extending archival research through the embodied, experiential nature of performance.”[93] The performative in this school of thought is attributed a historiographical function. As performances, reenactments and living history create meaning through (bodily) experiences that point beyond the traditional constructions of meaning based on written records and other storage media. According to performance-studies and theater-arts scholar Rebecca Schneider, the archive as a classic, regulating medium of storage and power regarding knowledge of the past is called into question by bodily practices of performance.[94] Reenactment performances with their physical modes of representation can bring about alternative visualizations of the past that contradict or even disprove written sources.[95]

Diana Taylor uses the term repertoire for history in and as performances, thus construing an alternative or expanded concept of archives.[96] Performance studies discusses the epistemological potential of this “felt connection” to the past when the historical character being portrayed merges with the ego of the actor: “In such moments, the performativity of reenactment evokes a poignant but transitory affective response in the reenactor.”[97] Katherine Johnson points out, however, that these “performative moments” are temporary and hence their inherent transformative power is limited. Reenactments understood as long-term and regular practices, however, combining present-day bodies with the materials, movements and behaviors of past bodies, can be of considerable value as epistemological and ontological resources.

Media studies points out with reference to living history that reconstructions with tactile elements are always mediated, i.e., communicated through certain media, and that past reality as a reference point has been mediatized in many ways as well. It also asks to what extent a person’s body can serve as a medium of experiencing someone else’s reality when “pictorial, textual and auditory inscriptions [are] (back) translated into bodily activities and/or material artefacts.”[98] The media-studies approach thus points out the multiplicity of media forms and formats in which reenactments can occur. Media philosopher Maria Muhle characterizes a potential analytical framework for reenactments as “the way it mediates (represents) a historical ‘subject’ […]. That is, we need to ask how it has gained access to the event that is being reenacted (through source study, oral transmission, analysis of historical documents etc.) and in what way it tries to conceal its own representative character (often by means of over-authentic representation that pays attention even to minor details).”[99]

Ethnology and sociology use elements of ritual theory to explain the character and potential of reenactment and living history. Victor Turner’s emphasis on a liminal phase in rituals that suspends social orders in a kind of intermediate state, subsequently restabilizing them, appears to be a fruitful concept.[100] Liminal phases, according to Turner, also have the potential for individual or collective transformations that are capable of creating new social realities. The dialectic structure of rituals corresponds to the dual character of reenactments, “which is characterized by both renewal and an affirmation of what already is.”[101] As the practices of living history are recreational activities done on a voluntary basis, we might consider them what Turner describes as liminoid. While it is true that reenactments are less standardized than classic rituals, they nonetheless resemble each other in manifold ways. Both of them manifest practices of creating identity, community and historical meaning, and both of them focus on corporeality.

Living history and reenactments are integral and influential components of historical culture, and yet historiography, despite its opening to include elements of public history, has been reluctant to acknowledge this method of addressing the past in the present. When living-history phenomena are investigated by academic historians it is often the more institutionalized forms (museums) that are foregrounded.[102] Individualized approaches such as reenactment are given short shrift and are thus mostly the subject of research in the aforementioned disciplines.

One of the reasons is simple: living history and reenactment, as phenomena largely grounded in the present, are largely inaccessible to purely historiographical research methods and require a mixture of ethnological approaches and oral-history methods. But historiography’s contribution to investigating the phenomena of living history is nonetheless important for an understanding of their historical dimension. Another explanation for the reluctance of historians[103] might be found in the different understanding of authenticity among scholars and lay people respectively. In historiography, authenticity is understood as the soundness of an argument relative to the amount of and access to available source materials.[104] The historical sources and their critical analysis are thus accorded “veto power,” allowing historians to disprove invalid conceptions of history.[105]

From the perspective of historical theory, historical meaning is created in the present (over and over again) using records and testimonies from the past. The experience-based history generated in the process of reenactment, by way of contrast, does not allow for a multiperspective and critical narrative. The personal experience of reenactors based on immersion, immediacy and physical-sensory participation in a historical reconstruction ultimately leads, in this perspective, to a subject authenticity that “prioritizes in experiential mode the subject and his or her emotional and lived-in world.”[106] Vanessa Agnew succinctly summarizes the focus on personal experience and its attendant claim to validity as follows: “[...] each actor offers his or her own version of the past – but not its lesson about the constructedness of history.”[107] The simulation of authentic historical reality that feels “real” to the active subject[108] offers a stark contrast to narrative history with its claim to rigorous scholarship and transparency in its continual attempts to make sense of the past.

Though this contradiction between academic and non-academic approaches to the past may seem indissoluble, both forms have a legitimate claim to existence. Their influence alone should be reason enough for academic historians to investigate more fully the various forms and intentions of historical culture in its everyday practices, harnessing their potential in the process of historical discovery.[109] It should be clear by now that this will necessarily be an interdisciplinary undertaking that can only succeed in dialogue with practitioners of living history.

Future research projects on living history and reenactment should therefore be grounded in cultural studies in the broadest sense of the word, incorporating historical expertise as well as an ethnographic perspective and the methodological tools to approach them as a modern-day phenomenon. Hitherto neglected gender perspectives might be mentioned here as a desideratum. The studies to date have based their knowledge of reenactment and living history on the description and analysis of male-dominated practices. A gender-sensitive treatment of the subject would therefore be a welcome addition, enabling a holistic understanding of these phenomena.

Translated from the German by David Burnett.

Recommended Reading

Vanessa Agnew/Jonathan Lamb/Juliane Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies. Key Terms in the Field, London 2020

Jay Anderson, Living History. Simulating Everyday Life in Living Museums, in: American Quarterly 34 (1982), no. 3, pp. 290-306

Anja Dreschke u.a. (eds.), Reenactments. Medienpraktiken zwischen Wiederholung und kreativer Aneignung, Bielefeld 2016

Wolfgang Hochbruck, Geschichtstheater. Formen der „Living History“. Eine Typologie, Bielefeld, 2013

Jens Roselt/Ulf Otto (eds.), Theater als Zeitmaschine. Zur performativen Praxis des Reenactments. Theater- und kulturwissenschaftliche Perspektiven, Bielefeld 2012

Sarah Willner/Georg Koch/Stefanie Samida (eds.), Doing History. Performative Praktiken in der Geschichtskultur, Münster 2016

Juliane Tomann, Living History (english version), Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 20.4.2021, URL: http://docupedia.de/zg/Tomann_living_history_english_version_v1_en_2021

![]() Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz „Creative Commons by-sa 3.0 (unportiert)“. Die Nutzung des Textes, vollständig, in Auszügen oder in abgeänderter Form, ist auch für kommerzielle Zwecke bei Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.de .

Dieser Text wird veröffentlicht unter der Lizenz „Creative Commons by-sa 3.0 (unportiert)“. Die Nutzung des Textes, vollständig, in Auszügen oder in abgeänderter Form, ist auch für kommerzielle Zwecke bei Angabe des Autors bzw. der Autorin und der Quelle zulässig. Im Artikel enthaltene Abbildungen und andere Materialien werden von dieser Lizenz nicht erfasst. Detaillierte Angaben zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie unter: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.de .

References

- ↑ Jan Carstensen, Uwe Meiners, and Ruth-E. Mohrmann, “Vorwort,” in: id. (eds.), Living History im Museum. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen einer populären Vermittlungsform (Münster: Waxmann, 2008), pp. 7-15, here p. 7. The term is often translated as lebende or gelebte Geschichte, literally “live” or “lived history.” Lebendige Geschichte (“living” or “vivid history”) is yet another possible rendering in German.

- ↑ Ibid., S. 7.

- ↑ Ibid., S. 7.

- ↑ Simone Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland? Nordamerikanische Living History Museen als außerschulische Lernorte,” in: Zeitschrift für Geschichtsdidaktik 5 (2006), pp. 44-69, here p. 48.

- ↑ Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland?,” p. 48.

- ↑ Irmgard Zündorf, “Zeitgeschichte und Public History,” version: 2.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 06.09.2016, http://docupedia.de/zg/Zuendorf_public_history_v2_de_2016 [05.05.2020]; see also the definition of “applied history” in: Jaqueline Nießer and Juliane Tomann, “Public and Applied History in Germany. Just Another Brick in the Wall of the Academic Ivory Tower?,” in: The Public Historian 40 (2018), no. 4, pp. 11-27, online at https://tph.ucpress.edu/content/40/4/11.full.pdf+html [05.05.2020].

- ↑ Cord Arendes, quoted in Zündorf, “Zeitgeschichte und Public History,” https://docupedia.de/zg/Zuendorf_public_history_v2_de_2016 [05.05.2020].

- ↑ Bodil Petersson and Cornelius Holtorf (eds.), The Archaeology of Time Travel. Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century (Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 2017) online at http://www.archaeopress.com/ArchaeopressShop/Public/download.asp?id={9B3CA03F-F66D-4F69-8158-B19208AA137F [05.05.2020]; Michaela Fenske, “Abenteuer Geschichte. Zeitreisen in der Spätmoderne,” in: Wolfgang Hardtwig and Alexander Schug (eds.), History Sells! Angewandte Geschichte als Wissenschaft und Markt (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2009), pp. 79-91. Jay Anderson also uses the concept of time travel in his foundational work from 1984: Time Machines. The World of Living History (Nashville, Tenn.: American Association for State and Local History, 1984).

- ↑ Michele Barricelli and Julia Hornig (eds.), Aufklärung, Bildung, „Histotainment“? Zeitgeschichte in Unterricht und Gesellschaft heute (Frankfurt a.M.: Lang, 2008).

- ↑ Juliane Tomann, “Memory and Commemoration,” in: Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb and Juliane Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies. Key Terms in the Field, (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020), pp. 138-142.

- ↑ Sarah Willner, Georg Koch and Stefanie Samida (eds.), Doing History. Performative Praktiken in der Geschichtskultur(Münster: Waxmann, 2016). Ethnologist Sharon Macdonald has chosen the term “past presencing” for the empathetic reconfiguration of the past. Sharon Macdonald, Memorylands. Heritage and Identity in Europe Today (London: Routledge, 2013).

- ↑ Eugen Kotte, “Reenactment – Grenzen und Möglichkeiten ‘gefühlter’ Geschichte,” in: Frauke Geyken and Michael Sauer (eds.), Zugänge zur Public History. Formate – Orte – Inszenierungsformen (Frankfurt a.M.: Wochenschau Verlag, 2019), pp. 120-140.

- ↑ Berit Pleitner, “Living History,” in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 62 (2011), no. 3/4, pp. 220-233, here p. 220.

- ↑ An overview is provided in: Jay Anderson, “Living History. Simulating Everyday Life in Living Museums,” in: American Quarterly 34 (1982), no. 3, pp. 290-306, here p. 291.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Bodil Petersson and Lars Erik Narmo, “A Journey in Time,” in: id. (eds.), Experimental Archaeology. Between Enlightenment and Experience (Lund: Lunds universitet, Institutionen för arkeologi och antikens historia, 2011), pp. 27-48, online at https://www.academia.edu/9990042/A_Journey_in_Time [05.05.2020].

- ↑ Gunter Schöbel, “Experimental Archaeology,” in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 67-74.

- ↑ Weitere anschauliche Beispiele bei Miriam Sénécheau and Stefanie Samida, Living History als Gegenstand historischen Lernens. Begriffe – Problemfelder – Materialien (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2015), p. 39.

- ↑ Sénécheau and Samida, Living History, p. 39; Wolfgang Hochbruck, “Living History. Geschichtstheater und Museumstheater: Übergänge und Spannungsfelder,” in: Living History in Freilichtmuseen. Neue Wege der Geschichtsvermittlung: Schriften des Freilichtmuseums am Kiekeberg; vol. 59 (Rosengarten-Ehestorf: Förderverein des Freilichtmuseums am Kiekeberg, 2008), pp. 23-35, here p. 25.

- ↑ A look at of the practice of first-person interpretation along with a critical assessment can be found in: “The Dilemma of First Person Interpretation,” in: Blog History: Preserved, 16.04.2013, https://www.history-preserved.com/2013/04/pros-cons-of-first-person-interpretation.html [05.05.2020]. Further examples from the practice in the United States can be found in: David B. Allison, Living History. Effective Costumed Interpretation and Enactment at Museums and Historic Sites (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), pp. 41-63.

- ↑ For a detailed account: Scott Magelssen, “Making History in the Second Person. Post-Touristic Considerations for Living Historical Interpretation,” in: Theatre Journal 58 (2006), no. 2, pp. 291-312.

- ↑ Dean, Living History, 2019.

- ↑ Jenny Thompson, War Games. Inside the World of Twentieth-Century War Reenactors (Washington: Smithsonian Books, 2004). The standard reference for Poland is the study of ethnologist Kamila Baraniecka-Olszewska on practices of authenticity in World War II reenactments: Kamila Baraniecka-Olszewska, Reko-rekonesans: praktyka autentyczności. Antropologiczne studium odtwórstwa historycznego drugiej wojny światowej w Polsce [Reko-rekonesans: Practices of Authenticity: An Anthropological Study of World War II Reenactments in Poland] (Kety: 2018).

- ↑ On World War I reenactments in Germany, see Stefanie Samida and Ruzana Liburkina, “Zwischen ‘Vatermörder’ and Feldgrau. Living History-Darstellungen zum Ersten Weltkrieg,” in: Monika Fenn and Christiane Kuller (eds.), Auf dem Weg zur transnationalen Erinnerungskultur. Konvergenzen, Interferenzen und Differenzen der Erinnerung an den Ersten Weltkrieg im Jubiläumsjahr 2014 (Schwalbach/Ts.: Wochenschau Verlag, 2016), pp. 224-243. See also Wolfgang Hochbruck, “Von ‘Flanders Fields’ bis ‘Fort Mutzig’. ‘Living histories’ des Ersten Weltkriegs als zweite Ableitungen der Vergangenheit,“ in: Barbara Korte, Sylvia Paletschek and Wolfgang Hochbruck (eds.), Der Erste Weltkrieg in der populären Erinnerungskultur (Essen: Klartext, 2008), pp. 157-168.

- ↑ A good overview of the development of the concept of authenticity is offered by Achim Saupe, “Historische Authentizität: Individuen und Gesellschaften auf der Suche nach dem Selbst – ein Forschungsbericht,” in: H-Soz-Kult, 15.08.2017, https://www.hsozkult.de/literaturereview/id/forschungsberichte-2444 [05.05.2020].

- ↑ The literature on reenactment and authenticity is very broad. The protagonists’ perspective of authenticity is the focus here: Anne Brædder et al. (eds.), “Doing Pasts. Authenticity from the Reenactors’ Perspective,” in: Rethinking History 21 (2017), no. 2, pp. 171-192. An overview of the discussion on authenticity can be found in Vanessa Agnew and Juliane Tomann, “Authenticity,” in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 20-25.

- ↑ Ulf Otto, “Re:Enactment. Geschichtstheater in Zeiten der Geschichtslosigkeit,” in: Jens Roselt and Ulf Otto (eds.), Theater als Zeitmaschine. Die performative Praxis des Reenactments (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), pp. 231-256, here pp. 240-247.

- ↑ Wolfgang Hochbruck, Geschichtstheater. Formen der “Living History.” Eine Typologie (Bielefeld: transcript, 2013), p. 93.

- ↑ This discovery is based on the author’s own field research, e.g., Interviews with actors of Revolutionary War Reenactment, Juliane Tomann, Feldnotizen in New Jersey & Pennsylvania 2016/2017.

- ↑ Gordon L. Jones, “Little Families.” The Social Fabric of Civil War Reenacting, in: Judith Schlehe et al. (eds.), Staging the Past. Themed Environments in Transcultural Perspectives (Bielefeld: transcript, 2010), pp. 219-235. A very readable portrayal, allowing you to immerse yourself in the world of the reenactor, is offered by Tony Horwitz, Confederates in the Attic. Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (New York: Vintage Departures, 1998).

- ↑ Stephen J. Hunt, “But We’re Men Aren’t We! Living History as a Site of Masculine Identity Construction,” in: Men and Masculinities 10 (2008), no. 4, pp. 460-483.

- ↑ Kotte, “Reenactment,” p. 126. Kotte refers here to the history didactician.

- ↑ Fenske, “Abenteuer Geschichte,” p. 81.

- ↑ Hochbruck, Geschichtstheater, pp. 97-110.

- ↑ E.g., in: Hochbruck, Geschichtstheater, pp. 123-129; Pleitner, “Living History,” p. 225c.

- ↑ Monika Weiß, Living History. Zeitreisen(de) im Reality-TV (Marburg: Schüren, 2019), p. 9; Georg Koch, Funde und Fiktionen. Urgeschichte im deutschen und britischen Fernsehen seit den 1950er Jahren (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2019).

- ↑ Pleitner, “Living History,” pp. 225.

- ↑ For a detailed account using the example of the “Stone Age: The Experiment” series: Matthias Jung, Archaische Illusionen. Die Vernutzung von Wissenschaft durch das Fernsehen am Beispiel der SWR-Produktion „Steinzeit. Das Experiment” (Frankfurt a.M.: Humanities Online, 2016).

- ↑ Sabine Lucia Müller and Anja Schwarz, “A Ready-Made Set of Ancestors. Re-Enacting a Gendered Past in The 1900 House,” in: id. (eds.), Iterationen. Geschlecht im kulturellen Gedächtnis (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2008), pp. 89-111.

- ↑ See also Pleitner, “Living History,“ p. 226c.

- ↑ Stéphanie Benzaquen-Gautier, “Art,” in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 16-20; Heike Engelke, Geschichte wiederholen. Strategien des Reenactment in der Gegenwartkunst – Omer Fast, Andrea Geyer und Rod Dickinson (Bielefeld: transcript, 2017).

- ↑ Maria Muhle, “Mediality,“ in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 133-138.

- ↑ Brian Rejack, “Toward a Virtual Reenactment of History: Video Games and the Recreation of the Past,” in: Rethinking History 11 (2007), no. 3, pp. 411-425, here p. 413.

- ↑ Clemens Reisner, “Das Verspechen des Reenactment: Der Spiel-Körper im digitalen Spiel 19 part one: boot camp,” in: Anja Dreschke et al. (eds.), Reenactments. Medienpraktiken zwischen Wiederholung und kreativer Aneignung (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016), pp. 257-281, here p. 259c.

- ↑ Pieter van den Heede, “Gaming,” in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 84-89; see also: Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History. How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (New York: Routledge, 2016); Annette Vowinckel, “Past Futures. From Re-Enactment to the Simulation of History in Computer Games,” in: Historical Social Research 34 (2009), no. 2, pp. 322-332.

- ↑ Living history does not define itself as being distinct from academic history; instead, living historians often seek to profit from a dialogue with professional historians or assist them in their scholarly endeavors.

- ↑ Erika Fischer-Lichte, “Einleitung. Theatralität und Inszenierung,” in: id./Isabel Pflug (eds.) (with the collaboration of Christian Horn und Matthias Warstat), Inszenierung von Authentizität, vol. 1: Theatralität (Tübingen: Francke, 2000), pp. 11-31.

- ↑ Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland,” p. 48.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies. Key Terms in the Field, (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020).

- ↑ Sénécheau and Samida, Living History als Gegenstand Historischen Lernens, p. 36.

- ↑ Hochbruck, Geschichtstheater, p. 24.

- ↑ For an introduction, see David Glassberg, American Historical Pageantry. The Uses of Tradition in the Early Twentieth Century (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1990); Amy Tyson, “Historical Pageantry,” in: Agnew, Lamb and Tomann (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies, pp. 163-169.

- ↑ Tyson points out that despite a participative approach, which aimed to include the broadest possible social mix in preparing and performing the pageants, the status quo was upheld during the performances. The most prestigious figures were played by urban elites and aristocrats.

- ↑ Sten Rentzhog, Open Air Museums. The History and Future of a Visionary Idea (Stockholm: Carlssons, 2007), p. 48c. More for Hazelius: Nils-Arvid Bringéus, Artur Hazelius and the Nordic Museum (Stockholm: Nordiska museets förlag, 1974), pp. 5-16; Daniel Alan DeGroff, “Artur Hazelius and the Ethnographic Display of the Scandinavian Peasantry. A Study in Context and Appropriation,” in: European Review of History – Revue européenne d’histoire 19 (2012), no. 2, pp. 229-248.

- ↑ Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 13.

- ↑ Hazelius quoted in Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 7.

- ↑ Hazelius quoted in Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 11. Some of the employees came from the Swedish provinces where the structures themselves came from. Rentzhog reports that there were residents from the province of Dalarna who came to Stockholm as seasonal workers and were hired by Hazelius at Skansen to demonstrate traditional folkways. Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 9.

- ↑ Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 12.

- ↑ Alan Gordon argues in a similar vein for Canada, where living-history museums had their heyday in the 1970s. Gordon sees other trends developing in museums starting in the 1980s which gradually began to replace living history. Alan Gordon, Time Travel. Tourism and the Rise of the Living History Museum in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016), p. 16.

- ↑ Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland,” p. 47.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 49.

- ↑ Scott Magelssen, Living History Museums. Undoing History through Performance (Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2007), p. 84.

- ↑ Magelssen, Living History Museums, p. 6, quoted on p. 81; for a detailed investigation: Stephen Eddy Snow, Performing the Pilgrims. A Study of Ethnohistorical Role-Playing at Plimoth Plantation (Jackson, Miss.: Univ. Press of Mississippi, 1993).

- ↑ The sign at the entrance, “Welcome to the 17th century,” marks off this space. The Internet homepage also welcomes visitors to the seventeenth century: https://www.plimoth.org/what-see-do/17th-century-english-village [05.05.2020]. See also Magelssen, Living History Museums, p. 86c.

- ↑ Williamsburg lost its political and strategic leadership role when Richmond became the capital in 1780. The physiognomy of the city changed accordingly. Buildings burned down or were torn down, others remained occupied, some were remodeled. The historic site had changed considerably by the time the decision was made in the 1920s to preserve the remains of the old town and/or reconstruct its state from 1780. See Christina Kerz, Atmosphäre und Authentizität. Gestaltung und Wahrnehmung in Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia (USA) (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2017), p. 170c.

- ↑ Kerz, Atmosphäre und Authentizität, p. 172. Rockefeller apparently spared no expense or trouble in creating a replica of colonial-era Williamsburg. He hired carefully selected historians and sometimes halted construction work if it turned out that the location of a building was off by a few meters from where the original had stood. “No scholar must ever be able to come to us and tell us we made a mistake,” Rockefellers quoted in Scott Magelssen, Living History Museums, p. 30.

- ↑ No admission is charged to enter the museumized town center; it is freely accessible. Fees are charged to take part in the various programs and tours or to visit the buildings where interpreters are working. Tickets are sold at the outlying Visitor Center, where an introductory movie is also shown.

- ↑ Kerz, Atmosphäre und Authentizität, p. 180c. Kerz points out that the publications of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation offer information about which parts of the scenes are based on historical facts and which are fictional in character.

- ↑ Sabine Schindler, Authentizität und Inszenierung. Die Vermittlung von Geschichte in amerikanischen historic sites (Heidelberg: Winter, 2003), p. 45; Kerz, Atmosphäre und Authentizität, p. 181.

- ↑ Schindler, Authentizität und Inszenierung, p. 43.

- ↑ Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland,” p. 50.

- ↑ Quoted in Schindler, Authentizität und Inszenierung, p. 48.

- ↑ Schindler, Authentizität und Inszenierung, p. 49c. The homepage of Plimoth Plantation offers detailed information on the various modes of representation at the village and the website, https://www.plimoth.org/what-see-do/wampanoag-homesite [05.05.2020]; see also Pleitner, “Living History,” p. 223.

- ↑ Jan Carstensen, Uwe Meiners and Ruth-E. Mohrmann, “Vorwort,” in: id. (eds.), Living History im Museum. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen einer populären Vermittlungsform (Münster: Waxmann, 2008), pp. 7-15. Living-history approaches are much more common in Scandinavian, British and Dutch museums than they are in German ones. The Zuiderzee Museum in Enkhuizen, the Netherlands, introduced first-person interpretation in 1990, whereas the Netherlands Open Air Museum (Openluchtmuseum) in Arnheim uses third-person interpretation. Adriaan de Jong, “Gegenstand oder Vorstellung? Erfahrungen mit Living History vor allem am Beispiel niederländischer Freilichtmuseen,” in: Carstensen, Meiners and Mohrmann (eds.), Living History im Museum, pp. 61-79.

- ↑ Rentzhog, Open Air Museums, p. 163.

- ↑ Nils Kagel, “Geschichte leben und erleben. Von der Interpretation historischer Alltagskultur in deutschen Freilichtmuseen,” in: Heike Duisberg (ed.) Living History in Freilichtmuseen. Neue Wege in der Geschichtsvermittlung (Rosengarten-Ehestorf: Förderverein des Freilichtmuseums am Kiekeberg, 2008), pp. 9-23, here p. 14.

- ↑ Kagel, “Geschichte leben und erleben,” p. 15.

- ↑ A controversy unfolded in 2008 when a performer representing a member of a Germanic tribe appeared at an event at the Paderborn Historical Museum with a tattoo on his stomach of the SS motto “Meine Ehre heisst Treue” (My honor is called loyalty) written in old-fashioned Sütterlin script despite prior instructions by the museum to refrain from using politically charged symbols. It is forbidden in Germany to display this slogan in public. The group denied that the man with the tattoo had right-wing tendencies, pointing out, furthermore, that he was not a regular member of the group. For a detailed account of the controversy, see Sénécheau and Samida, Living History, p. 121c.; Karl Banghard, “Unterm Häkelkreuz. Germanische Living History und rechte Affekte. Ein historischer Überblick in drei Schlaglichtern,” in: Hans-Peter Killguss (ed.), Die Erfindung der Deutschen. Rezeption der Varusschlacht und die Mystifizierung der Germanen (Köln: NSDOK, 2009), pp. 29-35.

- ↑ Sénécheau and Samida, Living History, p. 107.

- ↑ Duisberg (eds.), Living History in Freilichtmuseen; Carstensen, Meiners and Mohrmann (eds.), Living History im Museum. Stefanie Samida comes to similar conclusions in her analysis of the use of living history in German open-air museums: Stefanie Samida, “Performing the Past. Time Travels in Archaeological Open-air Museums,” in: Bodil Petersson and Cornelius Holtorf (eds.), The Archaeology of Time Travel. Experiencing the Past in the 21st Century (Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 2017), pp. 135-157, here p. 146c.

- ↑ Uwe Meiners, “Living History im Museum,” in: Barbara Christoph and Günter Dippold (eds.), Das Museum in der Zukunft – Neue Wege, neue Ziele!? (Bayreuth 2013), pp. 59-73, here p. 61.

- ↑ Pleitner, “Living History,” p. 223.

- ↑ Lässig, “Clio in Disneyland,” p. 58.