Publikationsserver des Leibniz-Zentrums für

Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam

e.V.

Archiv-Version

Anti-Semitism and Anti-Semitism Research

Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 01.07.2011 https://docupedia.de//zg/Benz_antisemitismus_v1_en_2011

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.2.287.v1

Definition and Manifestations

The word "anti-Semitism" serves on the one hand as a generic term for every type of hostility towards Jews. More specifically on the other hand, as a term formed in the final third of the 19th century, it characterizes a new, pseudo-scientific anti-Jewish prejudice that no longer argued religiously but employed qualities and characteristics associated with "race". A distinction needs to be drawn between the older religiously-motivated anti-Judaism and modern anti-Semitism.[1]

The working definition proposed by the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia serves as an instrument to gauge the political climate: "Anti-Semitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of anti-Semitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities. In addition, such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity. Anti-Semitism frequently charges Jews with conspiring to harm humanity, and it is often used to blame Jews for 'why things go wrong'. It is expressed in speech, writing, visual forms and action, and employs sinister stereotypes and negative character traits."

In modern language usage the term anti-Semitism covers the sum total of anti-Jewish statements, trends, resentments, attitudes and actions, irrespective of the religious, racist, social or other motivation behind them. Against the background of the experience of Nazi ideology and dictatorship, anti-Semitism is understood as a social phenomenon that serves as paradigm for forming prejudices and the political instrumentalization of the enemy stereotype constructed out of this paradigm.

The findings of interdisciplinary research tell us that hostility towards Jews is the projection of prejudices onto a minority.[2] For the majority, this mechanism serves various functions and has advantages. What is certain is that "the Jew" the anti-Semite refers to and fights, has nothing to do with real Jews and how they live. Rather, we are dealing with constructs, with images which stubbornly refuse to vanish, as the history of anti-Semitic prejudices proves – the oldest social, cultural, political resentment there is. Current manifestations of hostility towards Jews vary and reveal national peculiarities, for instance the secondary anti-Semitism in Germany and Austria, where the resentment fastens onto restitution and reparation payments following the Holocaust. Anti-Semitism evoking a racial argumentation is invariably present amongst the extreme Right, and this includes the denial of the Holocaust. While its dissemination is general, it varies in its intensity.

In contrast, religious anti-Judaism with its traditional forms ("deicide charge", legends of ritual murder) finds greater resonance in the societies of Eastern Europe. Of pressing concern at the moment is anti-Zionism, which in itself should not be equated with anti-Semitism, but due to the fanatic partisanship against Israel and the adoption of anti-Jewish stereotypes and argumentation models ("striving for world dominion", conspiracy fantasies) has developed into a special form of hostility towards Jews that is currently gaining widespread currency.

Hostility towards Jews in Western Europe has gained in intensity since the autumn of 2000. With the second Intifada, the Middle East conflict has attained a dimension that is played out far away from its actual location of Israel/Palestine. Young Muslims in France and Belgium, the Netherlands and Britain, i.e. in states where a relatively large share of the population has an Islamic background, express their solidarity with the Palestinians not only in anti-Israeli propaganda and at demonstrations, culminating at times in outbreaks of violence, but moreover they draw on and exploit traditional anti-Semitism for their purposes. In Eastern Europe hostility towards Jews serves as a leitmotif for the self-definition of national majorities. Prejudice against Jews functions as a catalyst for nationalist and fundamentalist currents and forms the common denominator for anti-liberal, anti-capitalist, anti-communist and anti-Enlightenment movements.

The roots of resentment against Jews in Christian self-understanding and the long social tradition of this prejudice mean that any attempt to explain anti-Semitism needs to explore its history.

The History of the Hostility towards Jews

Ever since Christianity was established as the state religion in the Roman Empire in the 3rd and 4th centuries, reservations vis-à-vis Jews in the Middle Ages were at first exclusively religious as well. At the same time however, in its existential scope, faith determined everyday life, and religious differences therefore had far-reaching consequences. Refusing baptism, sternly adhering to their rituals, their lack of understanding for the notion of redemption through Christ – in Christian eyes Jews seemed obdurate, betraying a "hardness of heart". This religious misunderstanding between minority and majority gave rise to the demand for visibly clear outward separation (from both Doctors of the Church and rabbis) between the believers of the Old Testament who saw themselves as the chosen people, and those who believed in redemption through Jesus Christ, i.e. in overcoming the Old Testament, and formed the majority as a Christian community. Christian doctrine considered the Jews to be "murderers of God" (St. Jerome of Bethlehem, 347-420); in early Christian fervor Bishop John Chrysostom of Antioch wrote that the synagogues were the den of Christ's murders – and in doing so established one of the most enduring stereotypes in hostility towards Jews.

Their religious rules, above all the strict observance of the Sabbath and the ritual dietary laws, forced Jews into an outsider role in medieval communities socially and economically. Excluded from exchanging goods (with the exception of small rural trade) and production by the Christian defined order of corporatist- and guild-based economic life, the economic activity of Jews was limited to dealing with money, prohibited to Christians because charging interest was seen as practicing "usury". Running pawnbroker businesses became a Jewish monopoly, protected by kings and princes, and a position Jews paid dearly for with heavy levies. Despite themselves being exploited, it was only the Jewish moneylenders who were exposed to the hatred of the debtors, and not those who tolerated, facilitated and utilized this financial system.

At the end of the 11th century religious antagonisms and social resentment grew stronger, merged and erupted in violence against the Jewish minority in Europe. The First Crusade (1096) – intended as a war against the "infidels" to liberate the Holy Land – was conducted by fanaticized Christians, who from the underclass as impoverished peasants, adventurers and the destitute acted out of social envy, initially against Jews throughout Central Europe. Besieged by the crusaders, Jews had the choice of either being killed or recognizing that the Christian faith was the genuine confession by receiving the sacrament of baptism. The persecution of Jews ended with the successful mission, for religious resentment was ultimately the motivation behind the persecution. Most Jews however opted for death.

As was the case with later Crusades, all of which were anti-Jewish, these acts of violence had the character of pogroms (the term pertains to a later period and was taken from Russian in the 19th century), i.e. the violence was not directed against individuals but all members of a minority, while, going beyond the religious-Christian motivation, plundering, theft and robbery were an inextricable dimension of the violence.[3]

From the 13th century onwards, legends and tales revolving around ritual murders and host desecration were spread to justify the aggressive hostility towards Jews. Legend has it that every year, at the emotionally and religiously sensitive time of Passion Week, Jews, out of hatred for Christ and Christians, would murder an innocent Christian boy in a ritual under the guidance of their rabbis – ridiculing the suffering of Christ. Following the Lateran Council of 1215, a second motif circulated, the blood libel, whereby Jews removed the blood of their victims to prepare matzos or for other medical or magical purposes. That such accusations were untenable is clear when consideration is given to the ritual imperatives of Jewish doctrine, which imposes sanctions on blood for Jews because it is held to be impure. Doctors of the Church and Popes repeatedly verified this, and emperors and kings defended the Jews against these blood libel accusations, albeit without success. Spread by those who held a vested interest in them, such as preachers and fanaticized mendicants gripped by missionary fever, the blood libel legends remained an effective trigger for persecuting Jews into the 20th century.

The hostile accusations were passed down in countless chronicles, stories, songs and sermons, and as shown by the example of Anderl von Rinn in Tyrol[4] the cult was tolerated by the official Church into the 1980s. Just how perilous these legends of ritual murder and blood libel were for the Jews is demonstrated by the pogrom in Kielce, Poland. Even in 1946 the rumor that a child who had disappeared had been killed by Jews was enough to spark days of disturbances resulting in the murder of at least 42 Jews who had survived the Holocaust.[5]

These images of Jews conjured by the clergy were followed by no less dangerous secularized versions which blamed the Jews for all evils. The plague epidemic in Europe in the mid-14th century gave rise to speculation that Jews had poisoned wells; here the Jewish minority was cast in the role of the stigmatized, replacing other groups previously blamed for earlier catastrophes, for example the Cathars (southern France 1321) or Muslims as infidels. For the first time a secular charge leveled against the Jews triggered a wave of pogroms between 1358 and 1360 during which most Jewish communities were destroyed. The Church served as a pacemaker for the following marginalization of Jews by secular authorities, by cities and towns, by the princes as the incumbents of territorial rule in Central Europe: the Lateran Council of 1215 had decided on the segregation of Jews and Christians. The "unbelievers" were to be made recognizable by wearing distinctive garments (yellow badge, Jewish cap) and live separated from Christians. This was the beginning of the ghettoization in the cities and the regulation of limited participation by Jews in public life through a host of discriminating rules.

The credit system changed in the 13th century. The Christian restrictions on interest were relaxed, and so Jews were now rivals in the financial business; only those customers borrowed money from them who were unable to obtain credit elsewhere. The image of the Jewish usurer was reinforced as an anti-Jewish stereotype, and the Jewish minorities in the cities, now generally in no position to fulfill their hitherto economic role, were demonized collectively and, like other marginal groups in society, exposed to the continuous threat of persecution. Following the example set by territorial lords (England 1290, France 1306, Spain 1492), beginning in the mid-13th century Jews were expelled from towns and cities, with a variety of reasons given and for the most part instigated by the local townsfolk. Religious, social and economic grievances formed a web of animosities against Jews, who with the exception of Prague and Frankfurt am Main had left the urban centers of Central Europe by the end of the Middle Ages. They scratched out a meager existence in villages as petty traders (peddlers, junk sellers).

With the traditional stereotypes of usurers, anti-Christians, well-poisoners and ritual murderers arising from Christian roots, complemented by religious customs mysterious in the eyes of Christians and the alleged character qualities derived from them, the Jews, members of a backward minority, were stigmatized without any culpability on their part (similar to heretics, sorcerers, witches), and they seemed not only to be deserving of loathing and disgust, but also the perfect object for missionary zeal. If, as was the rule, they resisted the lure of Christian baptism, they aroused the ire of the Christians all the more, as the example of Martin Luther shows, whose furious anti-Jewish sermons such as "On the Jews and Their Lies" from 1543 mirrors frustrated proselyte zeal. In the early Modern period Jewish missions replaced the forced baptisms of the Middle Ages (which were inadmissible according to canonical law), and along with them the devastating consequences, visible in Luther's reaction, whenever this pious intent came to nothing.[6]

In the Middle Ages the legal status of Jews was defined as servi camerae regis ("servants of the royal chamber") – first mentioned in documents in 1179 –, meaning that Jews were obliged to pay taxes but in return enjoyed a minimum of protection from persecution. With the emergence of territorial lordship the law passed into the hands of the princes. In the Modern period, [7] those Jews of interest to the territorial lords were privileged as "protected Jews", i.e. for payments of substantial amounts cash-rich Jews received permission to settle permanently. Jewish entrepreneurs frequently offered their services to princes in the period of absolutism, financing their costly ventures as the 'court Jew'. The most famous example of a court Jew in literature (and at the same time illustrative of the caprices the Jews were subjected to) is the history of Joseph Oppenheimer, who as "Jud Süß" served the Duke of Württemberg Karl Alexander, administered the duchy's finances and was publicly executed following the death of his protector; he was made the scapegoat for the ruining of the duchy's finances and the deterioration of estate rights under Duke Karl Alexander [8]

The Enlightenment paved the way for emancipation, influenced by the idea of tolerance articulated by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Moses Mendelssohn. The emancipation of the Jews, i.e. their liberation from social and legal constraints, in Germany and Austria was not a revolutionary act as in France (1791), but rather the outcome of a protracted debate lasting from the early 19th century to the end of the 1860s. As a counter to the legal equality of Jews, violence resembling the pogroms of the Middle Ages broke out in 1819. Beginning in Würzburg, the "Hep-Hep riots" spread across Germany and even reached Denmark. Flamed by social crises, but clearly a rejection of integration by the minority society, aggressive altercations with the Jewish minority took place. Hostility towards Jews was though a form of social protest where pent-up aggressions were shifted and redirected against Jews.[9]

Hostility towards Jews gained a new dimension in the 19th century in the form of a modern anti-Semitism which exploited racist and Social Darwinist arguments, and moreover presented itself as the result of well-founded scientific knowledge. Amongst its fathers was Arthur Count de Gobineau with his voluminous An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (published between 1853 and 1855 in four volumes), which although not explicitly directed against Jews, was instrumentalized as the cornerstone of a "racial theory" that seemed to lay down scientific foundations for anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitic theoreticians agreed in their claims that every "racial characteristic" of the Jews was negative, and the feature distinguishing it from the older anti-Judaism was the conviction that "racial characteristics" were, unlike religious beliefs, immutable. In the discussion of the "Jewish question" the parasite metaphoric played an ever increasing role, irrespective of the fact that the anti-emancipatory hostility towards Jews was also – and above all – a movement against the modernization of society and political liberalism.[10]

The intellectual peak of this conflict was the Berlin anti-Semitism debate, triggered by an article by Heinrich von Treitschke in the Preußische Jahrbücher in November 1879. The eminent historian had spoken out against a feared mass emigration of Eastern European Jews and accused German Jews of lacking the will to assimilate.[11]

Modern Anti-Semitism

Wilhelm Marr's political pamphlet Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum was published in February 1879; by the fall of the same year the twelfth edition was in print. The way had been paved by authors like Otto Glagau, who denounced the Jews as the cause for the economic crisis of 1873 that signaled the end of the boom years of the "Gründerzeit" in the widely read weekly Die Gartenlaube ("90% of the speculators and brokers are Jews") and stamped the Jews as scapegoats for all present-day hardships. The press campaigns in the conservative Kreuzzeitung, accompanied by Catholic papers – their common foe was political liberalism – deepened the anti-Jewish resentment swelling since 1874/75, as the economic crash was ongoing.

The Berlin court chaplain Adolf Stoecker (1835-1909), who, as the founder of a "Christian Socialist Workers' Party", had sought to convince workers and artisans of the advantages of the existing state order since 1878, hoping to lead them away from social democracy, exploited "the Jewish question" for his own purposes. He held anti-Jewish speeches, playing on the anti-Semitic expectations of his audience, drawing on the economic and social desires and fears of the petit-bourgeoisie plagued by worries and, by blaming "the Jews", offered explanations for and solutions to their problems. The idea to reconcile the masses of workers with the throne and altar through the clerical, anti-Jewish agitation proved to be of little appeal; at the same time however, this politicization of Christianity with anti-Semitic slogans left its mark on the Protestant Church into the 20th century.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855-1927), a private scholar greatly interested in the natural sciences, born in England and a naturalized German, prevented by psychosocial syndromes to pursue an academic or military career, became famous thanks to his historico-cultural work from 1899, Die Grundlagen des 19. Jahrhunderts; rejected by academic scholars, this bulky conglomerate of Germanic-centric ideas fascinated the educated bourgeoisie and made a striking impression on Kaiser Wilhelm II (and later Adolf Hitler).[12] Neurotically fixated on the antithesis between the "Jewish" and the "Aryan" race, Chamberlain worked with catchy stereotypes, for instance denying that Jews were capable of any kind of inward religiosity and fantasized on the alleged inflated influence Jews exerted in the modern world. No less ominous was the influence of Chamberlain's father-in-law who he revered and admired, Richard Wagner (1813-1883), whose reputation as a composer, music dramatist and writer transported his anti-Semitic convictions, expressed for instance in Wagner's striking and irrational essay "Das Judentum in der Musik" (1850).[13]

Overall, organized anti-Semitism was unable to achieve any political influence in the German Empire; in terms of its contribution to the cultural mood of the time however, the importance of the new anti-Semitism cannot be underestimated. The agitation against Jews and its public propagation in journalism, the catchphrases and postulates introduced into the public debate were seeds which only needed to wait for more favorable conditions to come to fruition.[14]

Anti-Semitism as a European Phenomenon

Anti-Semitism in Wilhelmian Germany was of course not some singular phenomenon, nor was it a German characteristic. In Austria, anti-Semitism emerged as a political movement in the 1880s from similar social and economical circumstances, initially from the social periphery, the petit-bourgeoisie. Anti-Semites found their first organizational basis in artisan cooperatives and guilds. At the same time, Georg Ritter von Schönerer agitated aggressively against Jews in the Imperial Assembly. The deputy Karl Lueger was the charismatic integrative figure of the Christian Social Party, which, similar to Stoecker in Berlin, exploited animosity towards Jews by merging it with an anti-liberal and anti-socialist politics. Unlike Stoecker and cohorts in the German Reich, the demagogy succeeded. After his supporters had gained the majority in the Vienna local council in 1895, Lueger was appointed mayor in 1897. The merits of his local politics have only served to marginalize the fact that they would not have been possible in the first place without the manipulative anti-Semitism galvanizing the Christian-Social base by appealing to the emotions.[15]

In France, which had granted its small Jewish minority (80,000 people, or 0.02 percent of the population) civil rights in 1791 as part of the French Revolution, anti-Semitic currents stemmed from a variety of motives. While Sephardic Jews in southern France encountered hardly any integration problems, the Ashkenazi Jews in the northeast faced animosity on a number of fronts, partly stemming from Christian-Catholic roots, partly from the form of racism formulated by de Gobineau and propagated by Edouard Drumont in La France Juive from 1886, and partly initiated by the socialists (a feature specific to France). Anti-Semitism was a factor integrating the diverse forces of nationalist and clerical opposition towards the Third Republic, perceived as a modern capitalist, secularized state.

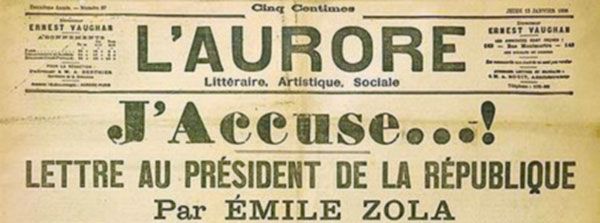

French anti-Semitism, incomparably more aggressive than its German manifestation, which was radical in its rhetoric, culminated in the Dreyfus Affair, which from 1894 held the French public in suspense for years. Charged with treason, the Jewish army captain Dreyfus was sentenced to deportation on the basis of falsified evidence in a dubious trial. Following the intervention of intellectuals (most famously Emile Zola with his open letter "J'accuse" in 1898), the proceedings led to the gravest constitutional crisis of the Third Republic, which ended with a Republican victory over the clergy, nationalists and anti-Semites. Anti-Semitism as an anti-modern political movement suffered a significant defeat in France, without however becoming completely irrelevant.[16]

Russia was synonymous for virulent and violent anti-Semitism at the end of the 19th century. Jews living in the rayon settlement in the west of the country were haunted regularly by pogroms, suffered great poverty and exposed to uncertainty as to their legal rights. Persecution intensified following the murder of Tsar Alexander II (1881). Generally, Jews in Russia (they were in fact to a large part Polish Jews under Russian rule) lived until the First World War in a situation comparable to Jews in Central Europe in the 18th century: as a marginalized minority without rights, denied any social status and thus excluded from any adequate opportunity to gain employment and advancement. Without the religious and – typical for Germany and France – racist and nationalist components, anti-Semitism was an instrument of anti-modern Russian politics.[17] The "Protocols of the Elders of Zion", a fake document from the Tsarist secret police allegedly proving a Jewish world conspiracy, were a key element in the politics defaming Jews in Tsarist Russia; beyond this direct influence, the "Protocols" became a reference text for anti-Semitism in general, circulated throughout the world and are still relevant today.[18]

In the First World War reservations about Jews in Germany were recharged. Despite the fact that German Jewry shared the enthusiasm for war sweeping the country in the summer of 1914 and that the number of Jewish volunteers was large – in relation to the Jewish proportion of the population – the rumor spread that Jews were "shirking". The second anti-Semitic stereotype commonly accepted was the conviction that Jews, the "born profiteers and speculators", were gaining untold riches, exploiting the adversity the fatherland was facing. As anti-Jewish petitions and denunciations gained in frequency from the end of 1915, the Prussian Minister of War ordered in October 1916 a statistical count on the service of Jews in the war. If this directive to conduct a "Jew count" was in itself an anti-Semitic outrage, the fact that the results remained unpublished made the affair a complete scandal. If, as claimed, the "Jew count" was supposed to officially prove how unfounded the complaints were, at the same time it sanctioned, because the result was kept secret, anti-Semitic resentments which had a long-lasting impact, which the Nazi Party and other rightwing parties were able to exploit for the duration of the Weimar Republic.

From Ideology to Genocide

Although the years between the First World War and the end of the Weimar Republic marked the highpoint of their cultural assimilation for German Jews, at the same time it was also the onset of social dissimilation. Anti-Semitic propaganda, which sought to lay the blame for the ignominious consequences of war defeat, the fears of social decline held by the petit-bourgeoisie and wounded German national pride turned "the Jews" into the culpable party. In the manifestos of the völkisch and nationalist parties of the postwar years, above all the Nazi Party from 1920 and the German National People's Party, anti-Semitism formed the ideological cement for binding the fear of losing one's livelihood with explanations for the economic and social problems, and was so key to winning over anti-republic and anti-democratic supporters. The result of this anti-Semitic agitation was the murder of Foreign Minister Rathenau in 1922 and the attempts to assassinate other democratic politicians of Jewish origin.

Anti-Semitism was of constitutive importance for National Socialism. Without undertaking any innovative efforts of their own, Hitler and the ideologues of the Nazi Party simply adopted the racial constructs and postulates of the hostile anti-Jewish sentiment from the 19th century. The manifesto of the Nazi Party from 1920 set out plans to revoke emancipation by reserving citizenship and positions of public office for non-Jews as well as placing a ban on immigration. Anti-Semitism was one of the central tenets in Hitler's programmatic Mein Kampf and was propagated in demagogic fervor at rallies as the remedy to all evils. The traditional stereotypes like the alleged Jewish striving for world dominion, the disproportionately large influence exerted by "Jews" in the media, culture, academia, etc, were the themes of this propaganda, "explained" by the constructs of 19th-century racial anti-Semitism. The "Protocols of the Elders of Zion" imported from Russia, the basis for the conspiracy theory explaining all that happened in the world, was also integral to this conglomerate, cited by Hitler, commented on by chief ideologue Alfred Rosenberg and circulated by the Nazi Party's own publishing operation. The lowermost abuse was the domain of Julius Streicher, the editor of the newspaper Der Stürmer, which launched vile tirades against Jews from 1923 up until 1945 under the motto borrowed from Treitschke, "the Jews are our misfortune".

Anti-Semitism became a policy objective of the state upon the Nazi Party assuming power in 1933: pushing Jews out of public life, out of business and society, then out of German national territory was the program. Following initial public excesses, for instance the boycott campaign of spring 1933 – "justified" by allegations that "Jews had declared war" on the German people – this policy was pursued through legal means. With the "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service" from April 1933, Jews were not only removed from public service but also socially outcast by the "Aryan paragraphs". Jewish lawyers were also prohibited from practicing in April 1933, while the "Editor Law" of October 1933 denied Jewish journalists employment, Jewish cattle dealers were no longer allowed to work, and doctors first lost their authorization then their license. The "Nuremberg Laws" of September 1935 marked the complete retraction of emancipation: Jews were no longer citizens of the German Reich but only nationals without political rights ("Reich Citizenship Law"). The "Blood Protection Law" forbid marriage with non-Jews and made sexual contact between Jews and "Aryans" a punishable offence, namely as an act of "racial defilement".

Propaganda complemented this discrimination by the means of the legal system. Highpoints were the exhibition "The Eternal Jew" in November 1937 in Munich which was subsequently shown in Vienna, Berlin, Bremen, Dresden and Magdeburg. The defaming propaganda show was the inspiration and source for Fritz Hippler's film of the same name, which was released in cinemas in 1940. The film was shown in dubbed versions in the occupied territories; the compilation film pretended to be a documentary, with anti-Jewish clichés montaged with mocking commentaries as a way of whipping up an antagonistic mood against the minority. Films like Jud Süß (Veit Harlan 1940) and Die Rothschilds employed more subtle means in striving to achieve the same objective.

Joseph Goebbels, chief of the Reich Propaganda Ministry, was not the only leading Nazi to spread hostile caricatures of Jews which paved the way to organized mass murder. Robert Ley, Reich organizational leader of the Party, agitated against the minority, while Göring was no less excessive in his anti-Jewish rants than Himmler and other potentates of the Nazi state.

The November pogroms in 1938 mark the transition from exclusion to persecution. Through "Aryanization" Jews were removed from business and the economy, their public life as a minority came to a standstill. The year 1939 brought restrictions of freedom of movement and with the "Jew houses" a form of ghettoization. The pressure exerted to coerce Jews into migrating, forced ahead in November with the imprisonment of almost 30,000 Jews in the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen, increased. New torments and cruelties were introduced once the war broke out (evening curfew, reduction of food supplies, prohibition to use cars, telephones, etc). With the "Madagascar Plan" the Foreign Office and the Reich Security Office considered deporting Jews to the island off the east coast of Africa in 1940.

The last phase of anti-Semitism put into practice began in the summer of 1941: the physical annihilation of the Jews. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, SS paramilitary death squads – the "Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD" – systematically murdered the Jewish population. The ban placed on Jewish migration and the wearing of the "Jewish badge" introduced in September 1941 prepared the way for the deportations to the ghettos and death camps in the East. When in January 1942 the Wannsee Conference was held, presided over by Reinhard Heydrich, the organized murder of Jews by way of mass executions was long in full swing, above all in the Baltic, Byelorussia and Ukraine. In the concentration camps of Auschwitz (from fall 1941) and Majdanek (fall 1942) Jews were murdered in gas chambers. An extermination camp was set up on Polish soil in Chelmno ("Warthegau") in the fall of 1941. The victims were suffocated in "gas trucks" without staying in the camp. In the three extermination camps run by the "Aktion Reinhardt", Belzec (November 1941), Sobibor (spring 1942) and Treblinka (June 1942), a total of 1.75 million Jews were murdered with gas by 1943. The ideology of anti-Semitism culminated in the Holocaust with the genocide of six million Jews.[19]

Anti-Semitism simply did not disappear with the collapse of the Nazi regime. Besides the traditional manifestations (Christian anti-Judaism and racial anti-Semitism), "secondary anti-Semitism" emerged as a reflex to the Holocaust, born out of feelings of guilt and shame, which, to name one example, focused on restitution payments. Increasingly relevant are those resentments expressed in the guise of anti-Zionism, which ostensibly targets the state of Israel, whose right of existence is disputed, but actually focuses on Jews collectively.

Theories on the Hostility towards Jews

The interdisciplinary character of research into anti-Semitism not only determines the pluralism of methods but also the host of explanatory models.[20] The diversity of theories on anti-Semitism corresponds to the diverse manifestations of the phenomenon. Historical interpretations, going back to the hostility towards Jews in ancient times,[21] function as forerunners in many respects. Historical studies depict "modern anti-Semitism" in the 19th century as a reflex-like reaction to a crisis of modernization,[22] one in which a variety of influences, traditions and patterns merge in the effort to respond to processes of social restructuring and the perceived decay of the values of civil society and its legitimacy. Nation and nationalism furnish an explanatory model for hostility towards Jews;[23] political positioning is also important and can result in characteristic expressions of anti-Semitism.[24] The crisis theory may be applied to various epochs, to industrialization as well as the period immediately after the First World War, and – partially at least – to the years following the fall of the Berlin Wall in Germany. Times of crisis are characterized by considerable social tension, and this gives rise to frustration and aggression which need to be vented and seek objects that fulfill the "guilty" function ("scapegoat" theory). The fear of losing individual and collective status is constitutive for the crisis model – in the crisis-ridden years following the "Wende" foreigners (asylum-seekers as well as longstanding residents) play the same role of the object of aggression as the Jews had in the modernization crisis of the end of the 19th century.[25]

Theories from psychology and psychoanalysis are long established in anti-Semitism research.[26] The theory of the authoritarian character[27] and the approach plotting the interaction between frustration and aggression are inconceivable without the insights of Freudian psychoanalysis. In collaboration with the social sciences, individual-based models (conflict with authority, education traumas, frustration out of inner conflict) have been extended in scope to cover groups; these theories define anti-Semitism in terms of prejudice structures which take effect in conflict situations and impact on the relationship between the (Jewish) minority and the majority societies.[28] Competitive relationships that are social and ethnic in origin play a salient role in such models; they are particularly helpful when interpreting conflicts originally stemming from rivalry, for instance xenophobia.

Experiences of or the fear of scarcities (often in combination with the threat of losing social status) are essential in the self-perception of social positions and shape behavior towards minorities, whose value and importance is seen as less than one's own. Based on this relationship, the deprivation theory explains the rise and impact of prejudices as emerging from experiences (e.g. with purportedly better-off migrants) which are set against the backdrop of the social advancement of a minority and the simultaneous decline of the in-group, and are articulated in negative stereotypes.[29]

Monocausal explanations fail to do justice to the complex phenomenon of anti-Semitism; the synergy generated by bringing together various disciplines, methods and theories is necessary. Due to its longstanding presence and diverse manifestations, anti-Semitism can be considered as an exemplary phenomenon for exploring group conflicts and social prejudices. Given current-day processes of migration and the new formation of societies with large ethnic minorities in Europe, many conflicts and problems are recurring structurally which are familiar from the history of how Jews and non-Jews have lived together. For this reason anti-Semitism research should not be limited to the narrower subject of hostility towards Jews. The scope must be broadened – from investigating this unique resentment and its impact to the more general and comprehensive problematic of prejudice and discrimination, the exclusion of minorities, and xenophobia. Taking general and overarching approaches, migration processes and minority conflicts are therefore also part of anti-Semitism research as is the history of the discrimination and persecution of individual sociological, ethic, religious and political minorities. The objective is to achieve an immersive approach to prejudice which can principally integrate every suitable field of research when it proves to be paradigmatic in character. Comparative studies are thus – corresponding to the diversity of methods – accorded great importance in anti-Semitism research.[30]

In this sense the concept of anti-Semitism needs to be extended and understood as a research strategy which includes phenomena like the persecution of Sinti and Roma or the discrimination of minorities, for example the "asocials", and looks into the ostracizing ideologies drawing on and propagating biological determinism, social Darwinism, racist anti-egalitarian currents and similar theorems. Youth violence, rightwing extremism and xenophobia are thematic fields of an anti-Semitism research that is seeking to furnish answers to complex constellations and analyzes multifaceted stereotypes of the enemy and prejudices in their political, social and cultural context.

In the face of current developments – the fixation on the threat posed to Israel by a spreading aggressive anti-Zionism, in particular in the Islamic world –, political interests are calling anti-Semitism research into question. The accompanying campaigns are undifferentiated and demand the taking of absolute positions. Whenever it refuses to serve a Manichean worldview, scholarly analysis and interpretation of hostility towards Jews are just as fanatically vilified as is the consideration of methods of discrimination against minorities other than the Jewish, necessary if this discipline's output is ever to be used paradigmatically. These aspects are viewed as relativizing the evil curse of this hatred towards Jews, which is to be solely deplored, and are fought against by political lobbyists and journalists with the misguided argument that the comparison (e.g. between the traditional practices of anti-Semitism and the approaches taken by "critics of Islam") devalues one while enhancing the status of the other.

Unlike the struggle against Holocaust denial and the incitement of hate out of nationalist and clearly evident racist motives, it is difficult to identify practical forms of combating hostility towards Jews. The best practice against resentments and prejudices resides in education and ongoing information campaigns, an approach substantiated by opinion polls and criminal statistics in all countries where there is an interest in the problem.

Recommended Reading

Alex Bein, Die Judenfrage. Biographie eines Weltproblems, 2 Bde., DVA, Stuttgart 1980, ISBN 3-421-01963-0.

Wolfgang Benz, Was ist Antisemitismus?, Beck, München 2004, ISBN 3-406-52212-2.

Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.), Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung, Bd. 1-10 Campus Verlag, ab Bd. 11 ff. Metropol Verlag, Campus/Metropol, Frankfurt a. M./Berlin 1992 ff., ISSN 0941-8563.

Wolfgang Benz, Werner Bergmann (Hrsg.), Vorurteil und Völkermord. Entwicklungslinien des Antisemitismus, Herder, Freiburg i.B. 1997, ISBN 3-451-04577-X.

Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.), Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Judenfeindschaft in Geschichte und Gegenwart, Saur, München 2009, ISBN 978-3-598-24071-3.

Wolfgang Benz, Der ewige Jude. Metaphern und Methoden nationalsozialistischer Propaganda, Metropol, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-940938-68-8.

Werner Bergmann, Antisemitismus in öffentlichen Konflikten. Kollektives Lernen in der politischen Kultur der Bundesrepublik 1949-1989, Campus, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, ISBN 3-593-35765-8.

Rainer Erb, Werner Bergmann, Die Nachtseite der Judenemanzipation. Der Widerstand gegen die Integration der Juden in Deutschland 1780-1860, Metropol, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-926893-77-X.

Hermann Greive, Geschichte des modernen Antisemitismus, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1983, ISBN 3-534-08859-X.

Klaus Holz, Die Gegenwart des Antisemitismus, Hamburger Editionen, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-936096-59-7.

Jacob Katz, Vom Vorurteil bis zur Vernichtung. Der Antisemitismus 1700-1933, Beck, München 1989, ISBN 3-406-33555-1.

Martin Kloke, Israel und die deutsche Linke. Geschichte eines schwierigen Verhältnisses, 2. Auflage. Haag & Herchen, Frankfurt a. M. 1994, ISBN 3-86137-148-0.

Peter G. J. Pulzer, Die Entstehung des politischen Antisemitismus in Deutschland und Österreich 1867-1914, Mohn, Gütersloh 1966.

Shulamit Volkov, Die Juden in Deutschland 1780-1918, Oldenbourg, München 1994, ISBN 3-486-55059-4.

Wolfgang Benz, Anti-Semitism and Anti-Semitism Research, Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 1.7.2011, URL: http://docupedia.de/zg/Benz_antisemitismus_v1_en_2011

Copyright (c) 2023 Clio-online e.V. und Autor, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <redaktion@docupedia.de>

References

- ↑ Cf. Thomas Nipperdey/Reinhard Rürup, Antisemitismus, in: Otto Brunner/Werner Conze/Reinhart Koselleck (eds.), Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, Stuttgart 1972-1992, vol. 1, 129-153; see also Christhard Hoffmann, Christlicher Antijudaismus und moderner Antisemitismus. Zusammenhänge und Differenzen als Problem der historischen Antisemitismusforschung, in: Leonore Siegele-Wenschkewitz (ed.), Christlicher Antijudaismus und Antisemitismus. Theologische und kirchliche Programme Deutscher Christen, Frankfurt a. M. 1994, 293-317.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz and Angelika Königseder (eds.), Judenfeindschaft als Paradigma. Studien zur Vorurteilsforschung, Berlin 2002.

- ↑ On anti-Judaism, see Johannes Heil, Gottesfeinde – Menschenfeinde. Die Vorstellung von jüdischer Weltverschwörung (13. bis 16. Jahrhundert), Essen 2006.

- ↑ Rainer Erb/Albert Lichtblau, “Es hat nie einen jüdischen Ritualmord gegeben”. Konflikte um die Abschaffung der Verehrung des Andreas von Rinn, in: Zeitgeschichte 17 (1989), 127-162.

- ↑ Rainer Erb (ed.), Die Legende vom Ritualmord. Zur Geschichte der Blutbeschuldigung gegen Juden, Berlin 1993.

- ↑ Thomas Kaufmann, Luthers Judenschriften in ihren historischen Kontexten, Göttingen 2005.

- ↑ Deutsch-Jüdische Geschichte in der Neuzeit, commissioned by the Leo Baeck Institute, ed. Michael A. Meyer assisted by Michael Brenner, 4 vols., Munich 1996-1997.

- ↑ Hellmut G. Haasis, Joseph Süß Oppenheimer, genannt Jud Süß. Finanzier, Freidenker, Justizopfer, Reinbek/Hamburg 1998; Selma Stern, Jud Süß. Ein Beitrag zur deutschen und zur jüdischen Geschichte, Munich2 1973 (1st ed. 1929).

- ↑ Jacob Katz, Die Hep-Hep-Verfolgungen des Jahres 1819, Berlin 1994.

- ↑ Werner Bergmann, Geschichte des Antisemitismus, Munich 2002; Reinhard Rürup, Emanzipation und Antisemitismus. Studien zur Judenfrage der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, Göttingen 1975.

- ↑ Ulrich Langer, Heinrich von Treitschke. Politische Biographie eines deutschen Nationalisten, Düsseldorf 1998; Karsten Krieger (compiler), Der Berliner Antisemitismusstreit 1879-1881. Eine Kontroverse um die Zugehörigkeit der deutschen Juden zur Nation. Kommentierte Quellenedition, im Auftrag des Zentrums für Antisemitismusforschung, 2 vols., Munich 2004.

- ↑ Anja Lobenstein-Reichmann, Houston Stewart Chamberlains rassentheoretische Geschichts-“philosophie”, in: Werner Bergmann/Ulrich Sieg (eds.), Antisemitische Geschichtsbilder, Essen 2009, 139-166.

- ↑ Dieter Borchmeyer/Ami Maayani/Susanne Vill (eds.), Richard Wagner und die Juden, Stuttgart 2000.

- ↑ Massimo Ferrari Zumbini, Die Wurzeln des Bösen. Gründerjahre des Antisemitismus: Von der Bismarckzeit zur Hitler, Frankfurt a. M. 2003.

- ↑ Doris Sottopietra, Variationen eines Vorurteils. Eine Entwicklungsgeschichte des Antisemitismus in Österreich, Vienna 1997.

- ↑ George Whyte, The Dreyfus Affair. A Chronological History, New York 2005; Daniel Gerson, Die Kehrseite der Emanzipation in Frankreich. Judenfeindschaft im Elsass, 1778-1848, Essen 2006.

- ↑ Heinz-Dietrich Löwe, The Tsars and the Jews: Reform, Reaction and Anti-Semitism in Imperial Russia 1772-1917, London 1993.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz, Die Protokolle der Weisen von Zion. Die Legende von der jüdischen Weltverschwörung, Munich 2007.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (ed.), Dimension des Völkermords. Die Zahl der jüdischen Opfer des Nationalsozialismus, Munich 1991.

- ↑ Herbert A. Strauss/Werner Bergmann (eds.), Current Research on Antisemitism, 3 vols., Berlin 1987; Lars Rensmann, Kritische Theorie über den Antisemitismus. Studien zu Struktur, Erklärungspotential und Aktualität, Hamburg 1998; Detlev Claussen, Grenzen der Aufklärung. Zur gesellschaftlichen Geschichte des modernen Antisemitismus, Frankfurt a. M. 1987.

- ↑ Zvi Yavetz, Judenfeindschaft in der Antike, Munich 1997.

- ↑ Rainer Erb/Werner Bergmann, Die Nachtseite der Judenemanzipation. Der Widerstand gegen die Integration der Juden in Deutschland 1780-1860, Berlin 1989; Shulamit Volkov, Die Juden in Deutschland 1780-1918, Munich 1994.

- ↑ Klaus Holz, Nationaler Antisemitismus. Wissenssoziologie einer Weltanschauung, Hamburg 2001.

- ↑ Matthias Brosch et. al. (eds.), Exklusive Solidarität. Linker Antisemitismus in Deutschland, Berlin 2007; Thomas Haury, Antisemitismus von links. Kommunistische Ideologie, Nationalismus und Antizionismus in der früheren DDR, Hamburg 2002.

- ↑ Samuel Salzborn, Zur Politischen Theorie des Antisemitismus. Sozialwissenschaftliche Antisemitismus-Theorien im theoretischen und empirischen Vergleich, Politikwissenschaftliche Habilitationsschrift, Gießen 2008.

- ↑ See the considerations drawing on social theory and psychoanalysis presented at the “Psychiatrisches Symposion zum Antisemitismus” in 1944 in New York: Ernst Simmel (ed.), Antisemitismus, Frankfurt a. M. 1993; Elisabeth Brainin/Vera Ligeti/Samy Teicher, Vom Gedanken zur Tat. Zur Psychoanalyse des Antisemitismus, Frankfurt a. M. 1993.

- ↑ Theodor W. Adorno, Studien zum autoritären Charakter, Frankfurt a. M. 1973; idem./Max Horkheimer, Dialektik der Aufklärung, Frankfurt a. M. 1986.

- ↑ Benz/Königseder (eds.), Judenfeindschaft als Paradigma.

- ↑ Cf. Wolfgang Benz, Antisemitismusforschung, in: Michael Brenner/Stefan Rohrbacher (eds.), Wissenschaft vom Judentum. Annäherungen nach dem Holocaust, Göttingen 2000, 111-120.

- ↑ Werner Bergmann/Mona Körte (eds.), Antisemitismusforschung in den Wissenschaften, Berlin 2004.