Topics related to movement are en vogue. Under the aegis of the concept of “mobilities”, researchers are examining the connections between different forms of movement through space (from alpine tourism to forced migration), as well as between movement and standstill. The state of being underway – including all of its conditions and consequences – is advancing to a subject of historical research in its own right. This article introduces the history of mobility as a heterogeneous interdisciplinary endeavour that contains several research fields, such as the histories of transportation, the environment, migration, tourism, and global history. This article recapitulates theoretical and methodological considerations from interdisciplinary mobility studies and highlights current research topics in the history of mobility, as well as the potentials and limitations of the field.

1. What is the History of Mobility?

Spatial mobility is an anthropological constant that is ubiquitous in the everyday lives of almost everyone. However, as the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman once observed, “Divided we move”.[1] Bauman’s pithy remark refers to the fact that human beings are mobile to different extents and in different ways; it has become the mantra of an interdisciplinary development that since 2006 has become loosely institutionalised as mobility studies under the keywords “New Mobilities Paradigm” or “Mobility Turn”. The representatives of this field, reacting to globalisation, have called for a sharper research focus on territorial mobility, particularly in sociology and geography. Like Bauman before them, they also opposed the metaphor of people in the twenty-first century as “global nomads”, rejecting the overly broad notion that globalization has made humanity mobile across borders.[2] In addition to tourists and the business class, adherents of mobility studies argue, the focus should also be on precariously mobile people such as migrant workers and refugees, as well as people who lack the means, rights or even the will to be mobile. As the sociologist Ronen Shamir put it in 2005, globalisation is a mobility regime and is based on “systemic processes of locking and containment”.[3] Research on inequalities in spatial mobility therefore serves both as a research agenda and a social critique in a globalised world.

While some researchers have gone so far as to speak of a new turn,[4] the reception of the New Mobilities Paradigm among historians has generally been restrained, although research on spatial mobility has become popular in recent years. In the study of history, mobility (from the Latin mobilitas) is generally understood as geographical movement. Historians working on the history of mobility are primarily concerned with the spatial movement of people, but they are also interested in the movement of animals, goods, objects, capital or information, as well as the causes, conditions and consequences of such changes of location.

The history of mobility is not an independent field; it is a cross-disciplinary thematic field that is neither clearly defined nor conceptualised. Mobility history covers entire fields of research such as the history of transportation, for which it is sometimes also used as a synonym, as well as the history of tourism and the history of migration. Compared to migration, mobility is another term, which, in addition to migrants, also includes all other mobile actors such as tourists, seafarers or diplomats, as well as potentially other living beings, things and data.[5] Furthermore, mobility history covers certain topics within larger historiographical fields, for example the history of urban mobility in urban history,[6] the history of (long-distance) trade in economic history, parts of infrastructure history and environmental history, cultural history studies on travel, and transit research in global history.

The concept of mobility features another component besides the mere change of location: it denotes the potential and facilitation of movement.[7] Whenever we speak of mobility, we are usually describing the mode, media and conditions of movement.[8] First and foremost, this entails the means of transportation and movement, as well as the underlying infrastructures and modes of transport, such as railways, airports or data cables. These structures enable the existence of mobility and embed it “in a network of social and technical components”, according to Eike-Christian Heine and Christian Zumbrägel in their Docupedia article on the history of technology. Mobility is therefore closely related to terms such as transportation and traffic,[9] which once again sets the term apart from migration.

In this context, the concept of mobility can also denote political and socioeconomic factors. This opens up analytical access to questions about such issues as the accessibility of transportation, inclusion and exclusion and the control thereof, meaning who or what can or is allowed to be mobile. In the 1970s, for example, transportation researchers, in an attempt to pivot away from the term ‘transportation’ (which was oriented towards anonymous structures), increasingly invoked ‘mobility’ to find a way to incorporate the needs of transportation users.[10] They inquired into which needs were associated with the mobilisation of people from different walks of life, income levels, and generations. Historians are also researching the interrelations between the history of mobility and social history. Such research focuses for example on the exclusion and segregation of marginalised groups within certain forms of transportation.[11] (Im)mobility and its conditions also have obvious relevance for disability history, where there is a great deal of research to be done.[12] Conceptually, however, spatial mobility must be considered separately from social mobility; the latter describes ascent or descent within social structures, and because such social mobility is not necessarily associated with a change of location, I do not consider it in this essay. I do want to point out, however, that spatial mobility often goes hand-in-hand with social mobility; sometimes the mobility of elites – for example in the form of stays abroad and academic exchanges – contributes to their further social advancement, while less privileged migration often leads to social decline.[13]

To highlight the differences and inequalities inherent in most forms of mobility, scholars, with increasing frequency, are invoking “mobilities”. This essay highlights the latest developments in the interdisciplinary field of mobility history, summarising the largely disparate findings and debates from different fields of historical studies that refer to mobility studies. My main focus here is on the mobility of people, which maintains the prior focus of mobility studies.[14] After examining the problem of mobility as a narrative of contemporary history, I offer an overview of the New Mobilities Paradigm. Then I move on to outline innovative trends where the examination of new concepts of spatial mobility is particularly visible: in transportation and environmental history, migration history, global history including tourism history, as well as in research with mobile methods and objects. Overall, I demonstrate why a concept of mobility – and mobilities in the plural – also appears to make sense for historical studies.

2. Increased Mobility as a Sign of Contemporary History?

The subject of mobility – if we understand the term in a way that also includes the transportation of data – appears to be particularly relevant to contemporary history. The associated aspects of reach, speed, frequency and volume – for the movement of people, goods and information – have all increased significantly under modernity. The notion has become commonplace that the world has become ever more networked and mobile in the second half of the twentieth century. If we examine the figures for global transportation between 1945 and 2015 – for example, statistics on air traffic, tourism and freight shipping – the steep upward trend is unmistakable.[15] Hardly any other global variable – neither the world population nor the global economy – has grown as enormously as the transportation of goods.[16]

Contemporary history has also witnessed revolutionary developments in passenger transportation. The rise of automobile traffic gripped the societies of Western and Central Europe (and somewhat earlier North America) when mass motorization, and thus a new form of individual transportation, began to develop from the 1950s onwards.[17] Civil aviation, which, like motorized private transport, had already begun in the first half of the twentieth century, also experienced a breakthrough after the Second World War; this formerly elite means of travel became a means of mass transport from the 1970s onwards. Finally, if we also include data traffic, there was a third major transformation in mobility, namely the spread of the Internet since the 1990s.

However, we should remain sceptical when we ask whether this increase in mobility is characteristic of contemporary history, despite upward trends whose social and economic consequences can hardly be overestimated. On the one hand, the mobility developments of the latter half of the twentieth century are part of a more far-reaching change. Many transportation historians agree that the first “revolution” in transportation in Europe – without which the history of industrialization and globalization would be unthinkable – took place in the early eighteenth century, with the expansion of infrastructures such as canals and roads and their optimized operation. The use of new means of transport ushered in a “second transport revolution”[18] between 1790 and 1850, when steam-powered ships and railroads transformed maritime and land transport; the telegraph decoupled the transmission of messages from mobile carriers.[19] In this respect, according to Jürgen Osterhammel, the second half of the nineteenth century can be understood as “a period of unprecedented network formation”.[20] Especially in global history, continuously accelerating “mobility was therefore often considered a sign and key element of modernity”.[21]

On the other hand, historians have often expressed doubts about the intellectual benefits of overly straightforward narrative arcs. A narrative in the sense of “faster, more often, further, more, more convenient, cheaper and safer” [22], as the historian Christoph Maria Merki puts it, is not entirely satisfactory for the twentieth nor the nineteenth century, as it is deceptively smooth and indiscriminate. If we look in a more nuanced way at the general growth trend, taking into account such issues as spatial distribution and social access to mobility, other narratives emerge that emphasize restrictions, complications and contradictions that are only superficially – or not at all – reflected in the quantitative recording of transportation figures.

Firstly, there is the danger of falling prey to a “mobility bias”:[23] you find mobility everywhere because you are explicitly looking for it. Sebastian Conrad’s warning about global history can be applied equally to the history of mobility; we must ensure that we “do not lose sight of those historical actors who were not connected in comprehensive networks, who would become victims of our present obsession with mobility, circulation and flows”.[24]

Secondly, we must make distinctions regarding the distribution of access options. The transportation networks that were built out with increasing density from the nineteenth century on permeated Western European societies to a far greater degree than in other regions of the world. Yet even within the Global North there were serious differences; to name just one example, the boom in passenger air transport after 1945 was nowhere near as significant for the citizens of the GDR as it was for their counterparts in the Federal Republic.[25] And of course there were, and are, marginalized groups everywhere – for example from the perspective of class, gender, ethnicity and disability – who benefit less from new transportation networks than others due to a lack of resources, political decisions or discrimination, but who for this very reason deserve the attention of historians of everyday life and social history.[26] This skews the ostensibly self-evident nature of mobility.

Thirdly, there are dialectics to consider. The accelerating expansion of transportation infrastructure since the eighteenth century favoured the formation and consolidation of nation-states[27] in which undesirable forms of mobility were suppressed. The history of a mobile modernity often went hand in hand with the forcible settlement and control of itinerant social groups and “vagabonds” in Europe, as well as nomadic communities in (semi-)colonial spaces.[28] One example comes from traditional migratory livestock farming in southeastern Europe: At the time of the Ottoman Empire, shepherds were able to move through broad ranges of land; however, the formation of new independent states and borders in the Balkans from the nineteenth century until the Second World War contributed, among other factors, to the decline of this form of mobility.[29] As we will see later, similar effects can also be observed for the history of migration. Since the nineteenth century, state control of migration by means of immigration laws, passport and visa requirements has also deterred potential migrants or at least forced them temporarily into immobility, for example in refugee camps or at fortified borders.[30]

Fourthly, we should not fall for determinism. Statistics that show the steady increase of human mobility and cargo in contemporary history do not mean that there is a law of continuous and unchecked growth. As can be seen from the example of air traffic, despite the exponential development of flight numbers over the last seventy years, there have been repeated moments of stagnation, for example due to the 1973 oil crisis, the Gulf War, or 9/11, as well as a recent dramatic slump due to the coronavirus pandemic.[31] Discussions about sustainability and the environmental costs of frequent flying, as well as pilot projects for car-free inner cities, also show that the reduction of mobility is part of past futures of mobility, at least at the discursive level.

For the European history of migration, we must also reject the idea of a constant increase in mobility (which is sometimes invoked as a horror scenario in political debates). Although emigration rates rose sharply after 1850 thanks to cheaper and faster transportation, people in pre-modern Europe were by no means inclined to be static and sedentary.[32] For German history, historian Steve Hochstadt used urban population registers to determine that the overall figures for both internal migration and immigration and emigration rates actually decreased beginning around 1920 compared to the previous century, despite the massive population shifts resulting from National Socialism and the Second World War. In the 1980s, migration rates in the cities were at roughly the same level as in the 1830s.[33]

All four points underline the problematic nature of a narrative describing a constant increase in mobility. While this narrative can be found in (historical) sources, we should not make the mistake of adopting it as an analytical framework. They also highlight the analytical benefit of the plural form “mobilities”, as it implies differences and inequalities. Furthermore, these four points demonstrate that mobilities are shaped by both practices as well as discourses. As the ethnologist Silke Göttsch-Elten has expressed it, mobility and immobility formulate “scenarios of threat, but also promises of a better world” which are used “to control mobilities”.[34]

3. Mobility in the Plural: The New Mobilities Paradigm

The sociologist Mimi Sheller, who in 2006, together with John Urry, published one of the seminal texts in mobility studies, describes the New Mobilities Paradigm as a “new type of thinking about social worlds”. These worlds are construed as the result of “complex and multi-scalar mobile relationships, flows, circulations, and their temporary moorings”,[35] whereby the term ‘moorings’ refers to the places, infrastructures, and institutions that enable and shape movement.[36] Urry and Sheller thus took up the spatial turn and the growing interest in networks and mobility since the 1990s. By emphasising cross-border forms of mobility, they also joined the transnational turn and its criticism of social analyses that are restricted to the nation state. Furthermore, they critiqued what they called “sedentary epistemologies”[37], noting that up to that point sociological analyses had focused on social mobility and neglected spatial mobility.[38] Geographer Tim Cresswell, who joined the chorus of sociologists, also called upon his discipline in the early 2000s to dedicate more attention to mobility, both within and between spaces.[39]

The result is not a unified theory; instead, it is a heterogeneous and eclectic conglomerate of theoretical considerations that has been and continues to be reproduced by mobility researchers from various disciplines, each with their own specialisations and definitions. Nevertheless, we can draw out a few premises here:

(1) Mobility is fundamentally different (“multiple mobilities”[40] based on Shmuel Eisenstadt’s term) and unequal (“uneven mobilities”[41]). The accessibility, potential and acceptance of mobility vary for different people and places. This calls for both analytical differentiation and an examination of unequal mobilities from the point of view of social distribution.

(2) Mobilities are understood relationally and transmodally. Different forms of mobility – meaning means of transport as well as groups of actors and reasons for mobility – are interrelated, interact with each other, and/or come into conflict. The reasons for and effects of such interactions should be analysed.[42]

(3) Dialectics of mobility and immobility should be revealed. We need to explain the extent to which the mobility of some is linked to the immobility of others, and when and why mobility turns into a temporary standstill. In addition, we must evaluate how “fixed” structures, i.e. institutions, infrastructures or territorial conditions, influence mobility.[43]

(4) Mobility is both functional and charged with subjective meaning. Therefore, we must take into account cultural perspectives about which ideologies, perceptions, discourses, and representations are associated with mobility, sedentarisation, and immobility – in other words, how mobility is “produced”[44], in a sense that extends beyond issues related to technical construction.

(5) The political organisation of mobility exercises a decisive influence on the mobility potential of different groups. The planning of mobility is associated with political promises that can never be fully inclusive;[45] mobility policy also manifests itself in concrete regulatory practices, from the debate about speed limits to the pricing policy of public transport providers, to security checks at airports, to passport and visa regulations in international travel.[46]

However, the New Mobilities Paradigm has not been spared criticism.[47] To some it seemed that this relatively small group of researchers made big claims (paradigm! turn!)[48] but tended to take little account of older research traditions in the humanities and social sciences on transport, migration, tourism, travel literature, etc. Mobility, pressed into service as a meta-theme, also seems too ubiquitous and at the same time too one-dimensional. One might ask whether any concept of mobility, however broadly and relationally conceived, can really do a satisfactory job of capturing the entire “social world”. It also remains questionable whether the various mobile phenomena – from human locomotion to objects, data streams, and imaginations – fit well under one analytical umbrella.

However, if the field of mobility studies is not measured by its most ambitious claims, but rather by the degree to which it has established itself as an innovative and interdisciplinary field, it can claim clear successes. This can be seen, for example, in the broad reception of fundamental texts, the founding of its own book series and journals such as “Mobilities”, “Transfers - Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies”, “Mobility in History” (until 2017), “Mobile Culture Studies” and “Applied Mobilities”, the establishment of research centres, and the strong visibility of mobility studies in organisations such as the “International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic & Mobility” (T²M), which was founded in 2003.[49]

4. Reception and the Potential of Mobility Studies in History

It is no surprise that historians have remained relatively unimpressed by proclamations of a new mobility paradigm. More recent perspectives, such as transnational and global history, have already taken extensive account of the growing interest in processes of cross-border mobility in historical studies since the 1990s. In addition, in established historical fields of research – one need only think of the history of transportation or migration – mobility was already at the centre of attention in the past, albeit under the guise of different terminology. We can therefore call into question the general idea that history has long focussed on the “stable aspects”[50] of societies. However, the New Mobilities Paradigm has not passed historiography by without a trace. As the following remarks illustrate, the idea of multiple and uneven mobilities, as well as the relational view of mobility and immobility, are also being taken up in the fields of historical studies.[51]

4.1 On New Roads: Transportation History as Mobility History?

In addition to the concept of transport, which primarily refers to the material and technical foundations of movement, and that of traffic, which focuses more on the level of organisation and “interaction of mobility carriers”,[52] the history of transportation has increasingly spoken of mobility since the 1970s in order to more strongly integrate user groups and their needs. In his 2008 introduction to the history of transportation, Christoph Maria Merki deliberately added the word “mobility” to signal that it is not only about the history of means of transport and transport systems, but also that of their passengers and stakeholders.[53]

The conceptual examination of mobility in transport history already took place before the New Mobilities Paradigm, but the latter has still found the most fertile ground of all historiographical fields here, as we can surmise from the topics in the Journal of Transport History or at the annual conferences of the International Association for the History of Transport, Traffic & Mobility. On the one hand, this is due to the fact that mobility studies itself revolves around transport and traffic issues. On the other hand, there was a certain hunger for conceptual renewal and more theoretical underpinning in transport history.

In Germanophone, Anglophone and Francophone scholarship of the 1990s, the history of transport and transportation was deeply embedded in the history of economics and technology, sometimes with the flavour of social history, but there was a lack of “approaches from the history of mentality and representation” on “spatial perception and travelling culture”[54], cultural studies perspectives on users,[55] and the topics of identity, gender roles, and everyday experiences.[56] According to railway historian Colin Divall, the older history of transportation ignored the fact that transport is both functional and meaningful.[57] Exceptions such as Wolfgang Schivelbusch’s “The Railway Journey” (1977) or Jeffrey Richards’ und John Mackenzie’s “The Railway Station” (1986), which were also received enthusiastically outside of the field of transportation history, existed for the nineteenth century but hardly at all for the twentieth.[58] Furthermore, transportation history focussed on the “modernising effects of transport”[59] in the Global North. Earlier eras, less technologised forms of mobility, and other regions of the world remained underrepresented.

a child observing the landscape through the window of a railway

carriage; cloud-castles in the sky. Source: Harper’s Magazine,

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010716300/ (public domain)

In view of these lacunae, it is not surprising that mobility studies have been, and continue to be, relatively widely received in the field of transportation history, as they are avowedly in favour of being open towards cultural studies and transnationalism. In his 2008 cultural history of automobility in the USA, Cotten Seiler for example took up innovative theoretical theses from mobility studies.[60] Gijs Mom, who also specialises in automotive history, has called even more explicitly on historians of transport history to adapt cultural studies and mobility studies.[61] On the other hand, many innovative works on transport topics have emerged since then that do not explicitly refer to mobility studies, but which emphasise cultural and user perspectives.[62] These include gender-historical studies on Radlerinnen (female cyclists) and self-propelled women in the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.[63] The same applies to studies on the interactions between different forms of mobility, such as conflicts between pedestrians and the emerging automobile.[64] These works point to the social relevance of certain forms of mobility such as automobiles or street cars before they became modes of mass transportation, and thus oppose the latent modernisation theme of older transport history.

Aside from those aspects related to cultural history, mobility studies can also inspire the history of transportation to connect with the traditions of transport research from the 1970s and to intensify social-historical lines of inquiry. In the history of infrastructures, Dirk van Laak has also identified the investigation of inclusion and exclusion effects as a subject that has been evident for some time but whose potential has not been fully exploited.[65] Structural factors such as ticket prices, travel class differences or a lack of transport connections should be considered, as well as everyday historical perspectives that weigh up the possible agency of excluded actors and marginalised social groups, be they stowaways, women driving illegally, migrants with forged papers, or homeless people who stay in indoor spaces such as airports or suburban trains.[66] Barbara Lüthi – in her work on Freedom Rides by civil rights activists protesting against racial segregation on public transport in the U.S. South in the early 1960s, and similar protest actions in Australia and the Palestinian West Bank – recently showed how mobility itself can become a form of protest that can be used to demonstrate against exclusion and for freedom of movement and rights.[67]

Not everyone involved shares Gijs Mom’s and others’ goal of transforming transportation history into mobility history.[68] Quantitative, economic and technical considerations continue to remain relevant. Mobility studies has also been accused of departing from classical transport history by neglecting commodity transportation.[69] The historian Reiner Ruppmann has described an “amorphous situation” [70] in which some transportation historians hold up mobility studies, while others continue to pursue empirical research, unaffected by findings in the newer field. The railway historian David A. Turner has expressed fears that the long-lasting lack of theoretical depth in transport history is now threatening to turn into a theoretical corset that excludes some researchers.[71] He has made an eloquent appeal for plural coexistence and co-operation within the field.

Current research topics anyway seem to extend beyond the usual repertoire of both mobility studies and “classic” transport research and challenge us to reflect together. One of the topics is in the turn towards the materiality of mobility, which for example Anne-Katrin Ebert, the Director of Collections at the Technical Museum of Vienna, has identified as a fruitful research agenda. The established historical research on infrastructures and technology could enrich mobility studies, which are strongly influenced by the cultural turn, and lead to new reflections on the material and technical conditions of mobility.[72] This also involves the examination of the level between planning and utilisation of mobility infrastructures, meaning operation, repair, maintenance, and conversions. At this intermediate level, we can discover everyday processes and dynamics that elude the modernist euphoria that often comes with new transport projects.[73] There we can also explore the “groundedness of the network society”,[74] i.e. the material dependency and susceptibility to disruption of modern societies, which easily fades into the background as long as systems are “in flux”.[75] Conversely, mobility studies encourage transport historians to emphasise actor perspectives. This would mean, for example, exploring the material practices of everyday actors such as passengers, technicians and operational staff, residents or even supposed “disruptors”, and asking how they appropriated, controlled or were at the mercy of technologies, vehicles and spaces.

4.2 Detour into Nature: Mobilities and the Environment

Another research potential lies in the field of mobility and the environment. As the transport historian Ueli Haefeli states, the focus on unequal mobilities and mobility justice in mobility studies tends to ignore the question of “how much mobility and transport” is actually desirable.[76] In view of current debates on sustainability, this is an urgent question that invites historicisation. For example, the articles in the thematic issue “Mobility and the Environment” in Zeithistorische Forschungen shed light on various relationships and conflicts between environmental discourses and transport practices.[77] Moreover, the question also touches on the meta-level of research practice and confronts historians who enjoy travelling with their own habits.[78] Current debates about the future of more sustainable mobility – from electromobility to urban micromobility to “flight shame” – also invite us to take a closer look at the mobility visions and fears of earlier times and to illuminate their effects on society and transport development. [79] Such glimpses into history also contribute to questioning the modernisation narrative outlined at the beginning; some historically older means of transport, such as the bicycle, now appear to be forward-looking and sustainable again.[80]

Current research on mobility and the environment are not limited to major problems such as pollution, climate change, and the destruction of the environment.[81] Historians are pointing out that the relationship between transportation, landscape and nature is more complex. Work on the history of the automobile in America, for example, shows how driving cars became a mobile culture of experiencing landscape and nature; this research also illuminates the cultural and political consequences caused by the advance of road-building.[82] Environmental history demonstrates that the existence of a “pristine natural landscape” is a myth, and that every perspective on nature has already been conditioned by human culture, technology, and knowledge.[83]

Conversely, other historians such as Nils Güttler have shown that even supposedly unnatural places such as airports are hybrid environments where nature can be found and where negotiations regarding the environment take place.[84] One example is found in the protests against the western runway at Frankfurt airport, and the central role they played in the environmental movement of the 1980s. The perspective of multiple mobilities also offers an interesting vantage point that enables us to view airports and other transit sites not just as hubs of global passenger and commodity transportation, but also as trans-shipment centres for animals, plants and pathogens. Mobility creates connections between the local environment and nature in other regions around the world, and we can assess in historical terms the consequences of such encounters.[85]

4.3 Same, same, but different? Global History and Mobility Studies

Mobility studies and global history (as well as the interdisciplinary global studies) have a great deal in common. They emerged at approximately the same time in the early 2000s. Inspired by such factors as sociological research on globalization and networks, as well as the transnational turn, scholars sought new ways to understand a contemporary world that was connected in border-crossing ways, yet evinced asymmetries. Accordingly, the terminology in these fields is similar, such as flows, networks, and connections. As Isabella Löhr has written, “While debates about transnational and global history were long occupied with the question of how the conquest of space affects the constitution of societies, mobility studies articulated a critique of that understanding of society which presumes territorial stability and the physical presence of all of its members.”[86] Another rarely noted commonality is the dialectical view of connections. Just as mobility studies conceives of mobility and immobility in relation to one another, there are increasing numbers of research centres in Germanophone Europe that view global history as the tension-filled interplay of de- and re-territorialisation, or that are dedicated to dynamics of connectivity and disconnectedness.[87] Despite, or perhaps because of, these parallels, few global historians, to date, have adopted mobility studies.

Global history almost always deals with mobility in the broadest sense, namely the transfer and circulation of people, materials and ideas. Overlaps with the theoretical concerns of the New Mobilities Paradigm occur primarily wherever considerations include the diverse assessments and political treatment or control of global mobility. This applies not only to the closely related subject of migration, but also to the entire spectrum of border-crossing mobility, including smuggling and other “deviant mobilities”, as well as privileged forms such as diplomacy, which seem interesting precisely because of how they are treated differently, their relationships, and their occasional intersection.[88] Even if the theory of the New Mobilities Paradigm postulates a broad understanding of mobility, empirical works often focus on a narrower sense of mobility, in particular traffic and transportation, especially of people. The thematic ranges of both fields can therefore only be brought under one roof to a limited extent; this is also because some of the typical global history topics – such as global microhistory, internationalism, visions of global order, cosmopolitan identities, and interculturality – are, to paraphrase the sociologist Gerard Delanty, “influenced by global mobilities, [yet] are not reducible to mobility”.[89]

Accordingly, productive intersections in terms of content are often found where global history is specifically concerned with transport routes and vehicles. One example is the history of forms of mobility in (post-)colonial contexts. The use of transportation infrastructures to infiltrate imperial spaces and shape global order has, since Daniel Headrick’s “Tools of Empire” (1981), been a classic theme of imperial-, colonial, and later global history.[90] More recently, some have criticised the Eurocentric focus on technological means of transportation and their Western profiteers and operators; instead, there are references to older research from area studies that dealt with local modes of transport such as camels, caravans, and porters – a topic that has recently regained importance.[91]

Studies on the use or appropriation of infrastructure technology by indigenous elites and inhabitants, before and after decolonisation, also open up a change of perspective.[92] Transmodal approaches are particularly innovative here; for example, Valeska Huber, in her book “Channelling Mobilities”, reconstructs the interaction of various forms of traffic on the Suez Canal around 1900, where traditional caravans encountered imperial steamships and their European passengers. Huber explicitly employs the concept of multiple mobilities to examine various practices of mobility and how they were perceived in different ways, as well as their political configuration.[93] Similarly, Lasse Heerten has followed the approach of tracing different mobilities in global port cities.[94]

Historical transit research provides a second example for an analytically productive enmeshment of global and mobility history. While approaches taken from global history generally inquire into why, how and with what consequences people create cross-border connections, transit research focuses its attention on the connections themselves, for example on the functionalities and inherent logics of telegraph networks, or the experiences and interactions onboard transoceanic steamships.[95] Thus far, this still relatively new field of research has focused on ocean liners, and there is still plenty of scope for investigating transit in other modes of transport, transit locations, and later time periods. In doing so – and here mobility studies could once again provide inspiration – the divergence of the transit experiences of different groups of actors and especially precarious forms of mobility should be given greater consideration. In an essay on Indian and Chinese crew members on European steamships around 1914, the historian Gopalan Balachandran has impressively shown that being mobile could itself be restrictive.[96] For the modern era, this argument makes immediate sense, for example when we think of the Middle Passage in the history of slavery. In more recent contemporary history, there are very few studies that examine inequalities in transit experiences in the context of globalization (for example, the crews of freighters or cruise ships).[97]

The history of tourism provides a third example of the intersections between global history and histories of mobility. This is an independent field of research that, however, has much in common with global history when it comes to cross-border, colonial or otherwise transcultural tourism and the consequences for, or interactions with, the local population.[98] In the history of tourism, the mobility turn was received just as intensively as in the history of transport.[99] However, following the tourism historian Hasso Spode, we can ask critically whether the theoretically hyped premise that everyone and everything is mobile does not lead to “tourism [drowning] in a sea of mobilities”.[100] This development could detract from the analytical tangibility of the phenomenon of tourism. On a positive note, Spode has noted the “merit of the mobility turn” insofar as it “sharpens the focus on the blurred”[101] – that is, on the often-fluid boundaries between tourism and everyday life, as well as between tourist travel and other forms and functions of being mobile.

Several historians have identified the overlaps between tourism and other forms of mobility as an original contribution from mobility studies.[102] Empirical studies that relate tourism and migration to each other are a good example of this.[103] Mobility studies also provide theoretical considerations on the relationship between mobility and immobility. Such considerations can help to historically analyse the relationships between tourism mobility and the societies, environments and people (especially locals and local seasonal workers) who are affected by it on the ground.[104] Gabriele Lingelbach and Moritz Glaser have also identified these relationships, which are often characterised by cultural othering, asymmetries and hybridisation, and their consequences as a desideratum of a history of tourism which is expanding in both global and historical scope.

However, mobility studies could also provide inspiration for global history beyond the topics mentioned above. On the one hand, this concerns mobile methods, which will be discussed later in this article; on the other hand, it concerns the debate on the future viability of global history. In recent years, global history has been accused from several sides of neglecting the “losers of globalisation”, those “left behind” and the less mobile.[105] Others have emphasised that global history also looks at the “dark sides” of networking and the dynamics of re-territorialisation and disentanglement.[106] The socio-critical impulse behind the New Mobilities Paradigm can also be instructive, without having to adopt the normative concept of “mobility justice” as advocated by Mimi Sheller. In line with the historian Hans-Liudger Dienel’s diagnosis that the “effects of increased mobility on mental globalisation” constitute “a field that has been far too little explored to date” [107], future studies could investigate the consequences of restricted mobility on global integration processes and also take into account how people assess their own (im)mobility.

4.4 Migration History on the Move

Mobility and migration are often mentioned in the same breath, whereby mobility, as a generic term, tends to include more actors than just migrants. The boundary between different types, occasions and intentions of mobility is not always clear. This can be exemplified by the situation of ‘guest workers’ in the Federal Republic of Germany between the 1950s and 1980s. Initially, labour migrants were recruited with the intention to employ them on a temporary basis, before many Turkish workers in particular decided to settle in Germany in the 1970s and bring their families from their countries of origin with them.[108] Another example is German tourists who choose the Canary Islands or Thailand as their retirement destination, and thus become migrants later on in their lives.[109]

The relationship between the history of mobility and the history of migration, however, is much more than just blurred categorisations. Rather, there are several thematic intersections that either still have innovative potential or are even just being discovered by historians. In contrast to the history of transportation, where the reception of the New Mobilities Paradigm represented a reaction to the desire for theoretical innovation, migration history is not lacking in theoretical impulses due to its close connection to the interdisciplinary field of migration studies. The proximity to the New Mobilities Paradigm results here more from the similarity of many questions and approaches in migration studies and mobility studies, which can be seen in three interfaces:

(1) The first intersection results from the entry of transnational perspectives into the history of migration since the 1990s. Previously, migration was usually viewed as a unidirectional movement from one country to another, often within the nation-state framework through the lens of the country of origin or immigration; this is now considered a methodological dead end. Researchers, above all the anthropologist Nina Glick Schiller, have increasingly focussed on the subsequent mobility of migrants.[110] Topics such as communicative exchange, visiting trips and cultural connections back to the home country or to communities in other countries, as well as cases of remigration, were given greater consideration. They shift the focus away from one-sided questions of integration or push-pull models towards circular and chain migration, transnational social spaces and visits, hybrid identities, diaspora cultures and cross-border knowledge circulation.[111] In these cases, migration merges seamlessly into other forms of mobility. In addition, research into the means of transport, routes[112] and communication media[113] on which transnational contacts are based can provide insights into the functioning of post-migrant networks.[114]

(2) However, the transnational euphoria of the 1990s has also been criticised in the history of migration. Borders and immigration restrictions are now increasingly taking centre stage.[115] Research on historical migration regimes – i.e. systems for the regulation and control of migration – is not only analytically close to Border Studies; it also fits in with the aim of mobility studies, which is to examine the dynamics of mobility and immobility, uneven mobilities and political mobility control.[116] An important research desideratum in this context is the discursive relationship between migration, other types of mobility and sedentariness; according to historians Anne Friedrichs and Maren Möhring, migration can only be problematised and devalued if sedentariness is constructed as the norm.[117] Some migration historians follow the maxim of the New Mobilities Paradigm to examine different mobilities in context and with a view to hierarchisations. For example, Francesca Falk recently suggested using one place as an example to “compare the political and social treatment of refugees and tax evaders in a very concrete way”.[118] Cultural anthropologist Ramona Lenz, who has studied the coexistence of tourists and migrants on Crete and Cyprus, shows how the otherwise abstract theory of the nexus of different (im)mobilities can be made empirically tangible without remaining stuck in the superficial juxtaposition of “poor refugees and wealthy business travellers”.[119] Research on “stay-at-homes” and their family members who have moved abroad also shows that migration and immobility are not pure opposites; they can form part of a joint household strategy based on transnational remittances sent back home by the migrants.[120]

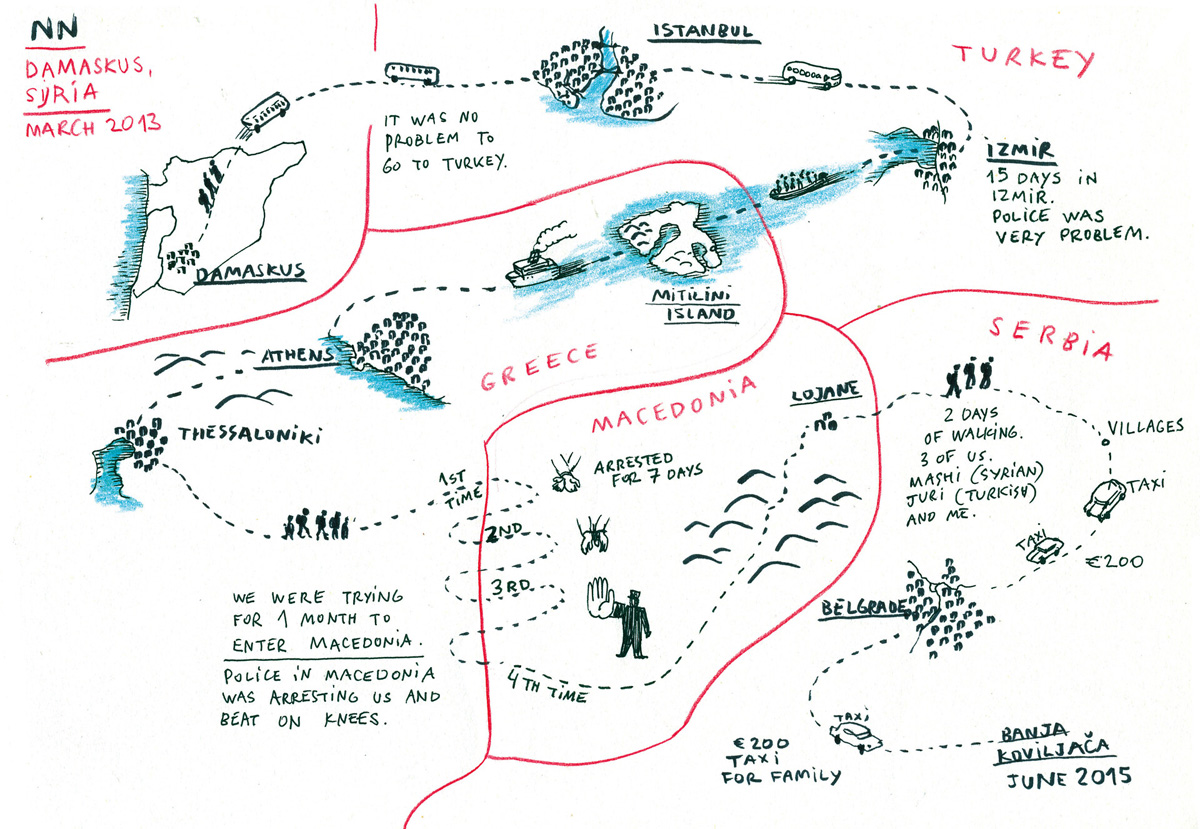

(3) Perspectives from mobility studies can also be stimulating when it comes to asylum and forced migration, i.e. flight and expulsion. The transport infrastructures, means of travel, routes and transit points of migrants and refugees are only gradually becoming the focus of historical migration research.[121] Interest here focusses on the spatio-temporal in-between, i.e. on “transit migration”[122] and migration routes that lead in different directions.[123] An analysis of subjective reflections and interactions in transit can reveal their function in coping with the transition between spaces, identities and stages of life. Ship passages and comparable phases of being on the move are particularly suitable for such an investigation, as a look at the history of Jewish flight and exile shows.[124]

Research on global migration, asylum and flight in recent history is also increasingly focussing on migration routes and the spaces in between. Such research goes beyond subjective transit experiences to also include migration regimes, which are traced en route, so to speak.[125] During their journeys, migrants have to manoeuvre through places such as camps or border zones and through bureaucratic practices such as passport controls or changing framework conditions. Complications and new situations can change their plans and direction of travel, and some get stranded in transit or turn back.[126] Within Border Studies, scholars have turned the tables and found that borders themselves, and their guardians, are mobile; the Frontex patrols in the Mediterranean offer just one example of this phenomenon.[127]

Transit research within migration history therefore assumes that migration processes are rarely linear; they tend to be contingent and spontaneously protean. The political scientist William Walters’ concept of “viapolitics” – with which he builds a bridge between migration research, transport studies and “mobile” methodology (see below) – also holds promise for future research. Walters considers means of transport and routes as sites of engagement with migration regimes, thus opening up a topic that is also of interest to historians.[128]

A related topic that has received little attention in transport and mobility studies, but has long been dealt with in migration history, is forced mobility, i.e. specifically relocations, expulsions, and even deportations and the transport infrastructures that facilitate them. For Holocaust research, there are corresponding studies that examine the role of ramps and railways.[129] Pioneering work by Ethan Blue and William Walters examines the role of trains and aeroplanes in the history of deportations of foreigners and demonstrates the value of a focus on deportation infrastructures.[130]

4.5 Mobile Methods and Objects

Last but not least, mobility studies also stand for the development and use of what are called mobile research methods.[131] These approaches aim to capture, track or simulate the various “mobile systems and experiences that seem to characterise today’s world”.[132] These include sociological and ethnological methods such as participant observation as “going along”, the use of tracking techniques with GPS, video ethnography, the recording of time-space diaries or travel blogs, and the observation of transit sites such as airports and camps. Older sources of ideas were in particular Georg Marcus’s “Multi-Sited Ethnography” (1995), James Clifford’s ethnology of “routes” (1997), and the “Follow the Actors” approach of actor-network theory.[133]

To what extent does it make sense to integrate mobile methods into historical studies? In fact, there are already methodological approaches that resemble a kind of retrospective tracing and reconstruction of paths of movement. These include the previously outlined transit research from global history and migration history as well as global biographies[134], commodity chain analyses[135] or, more generally, working with source types that seem particularly suitable for tracing movement in space, or its representation and reflection; for example diaries, correspondence, postcards, travelogues, passports or historical maps and drawings that depict routes and movement patterns.[136] With the aid of new digital methods, in particular geoinformation systems, maps can also be used as a research method to depict and analyse spatial-geographical movements and their progress over time.[137] Other approaches, which are also still relatively new and focus on “travelling” objects, are provenance research[138] and research on material culture on the move, things in exile.[139]

In an article in Geschichte und Gesellschaft from 2016 that was strongly reminiscent of the New Mobilities Paradigm, Monika Dommann argued that historiography should become more “nomadic”. She sees migration history and the history of infrastructure and transport as pioneering fields for moving away from circulation narratives, which used to be popular in the history of knowledge and global history. Instead of circulation, they would tend towards a “radical follow-the-movement heuristic” that produces studies of movement as well as “standstill” and explores the causes and effects of mobility and standstill.[140] Bettina Severin-Barboutie’s study on “Migration as movement” could be seen as a concrete realisation of this. Instead of solely investigating the integration of migrants in the two cities she analyses (Stuttgart and Lyon), Severin-Barboutie juxtaposes the practices of arrival with practices of immobilisation, onward travel and return, which she understands as “multi-sited historiography”, based on James Clifford.[141] Anna Lipphardt, an ethnologist who applies historical methods in her work, and her project team also choose a mobile research perspective in order to analyse the “mobile living environments” of members of the Yenish and, en passant, the respective residence regimes.[142]

Mobile perspectives can lead to profitable insights. However, human geographer Peter Merriman has rightly expressed concerns with regard to the mobile methods of mobility studies, which can be applied to historical studies in a similar way. He argues that it is simply not possible or sensible in terms of source technology to follow the moving elements and actors for all topics. Moreover, not all practices that have to do with movement can be best captured with “follow the ...” perspectives: The material, socio-cultural, political and economic contexts in which mobility is embedded are often decisive, even if these contexts themselves do not “travel” and cannot always be fully recognised en route. Finally, the implicit idea that a mobile perspective is “closer” or even more authentic also appears questionable from an epistemological perspective.[143]

5. Conclusion

The history of mobility can hardly be reduced to a common denominator; it is a heterogeneous cross-sectional field that is difficult to survey. It brings together different topics, questions, and theoretical and methodological approaches that explore the connections between different forms of mobility, between movement and standstill, as well as between being on the move and the resulting contexts and connections between people, places and things.[144] This review of the current research landscape – especially in the history of transportation and the environment, global history, tourism and migration history – has shown that the terms “mobility” and “mobilities” are booming and have increasingly established themselves alongside such terms as transportation or migration in recent years. Even if these terms lack a standardised definition, conceptual similarities are noticeable in their use in the various fields: Wherever “mobility” or “mobilities” are mentioned, the reference usually points to research perspectives that analytically strengthen the means, media, infrastructures, and conditions of spatio-physical mobility, emphasising the mobile actors and their agency. What is also striking is the valorisation of phases of transit and being on the move as independent historical research topics that can also be analysed with mobile methods.

The plural form “mobilities” also signals a growing interest in how different forms of mobility, or various mobile groups, interact or are related to one another. There is an increasing demand for scholars who analyse mobility to pay more attention to inequalities, dialectics of mobility and relative immobility, as well as mobility control. As this article has shown, a concept of mobility in the plural is already being used productively in various fields of historical scholarship, in a way that does more than just describe different mobilities and also seeks to explain their causes, meanings and consequences.[145] In short, people’s past experiences of mobility are becoming more visible. However, this means that the movements of goods, raw materials, waste, data, and other things have tended to be neglected in the history of mobility – unlike in the older history of transport and traffic.[146]

These trends in the history of mobility can be linked to interdisciplinary mobility studies, but they do not always stem from them; rather, they are also rooted in the respective historical field’s own lines of genesis, or can be traced back to influences such as the cultural and transnational turn. Mobility studies offer theoretical points of reference and interdisciplinary perspectives for research into the history of mobility that could be more widely utilised. However, summarising the history of mobility in an overarching framework, based on the New Mobilities Paradigm, does not seem to make much sense, and poses a hindrance to the analytical creativity and dynamics of the respective fields of historical research.[147]

Translated from German by Lee Holt.

References

[1] Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization. The Human Consequences (New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1998), (p.) 85.

[2] On the criticism of the nomad metaphor, see Ada Ingrid Engebrigtsen, “Key Figure of Mobility. The Nomad,” in: Social Anthropology 25 (2017), vol. 1, (pp.) 42–54, online https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1469-8676.12379 [16.10.2024].

[3] Ronen Shamir, “Without Borders? Notes on Globalization as a Mobility Regime,” in: Sociological Theory 23 (2005), vol. 2, (pp.) 197–217, here (p.) 197; see also Nina Glick Schiller/Noel B. Salazar, “Regimes of Mobility across the Globe,” in: Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (2013), vol. 2, (pp.) 183–200; Rey Koslowski (ed.), Global Mobility Regimes. A Conceptual Framework (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).

[4] See for example Mimi Sheller, “Form Spatial Turn to Mobilities Turn,” in: Current Sociology 65 (2017), vol. 4, pp. 623–639.

[5] On mobility as a broader concept compared to migration, see also: Barbara Lüthi, “Migration and Migration History,” Version: 2.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 06.07.2018, http://docupedia.de/zg/Luethi_migration_v2_en_2018 [16.10.2024].

[6] For intersections between mobility history and urban history, see: Lasse Heerten, “Mooring Mobilities, Fixing Flows. Towards a Global Urban History of Port Cities in the Age of Steam,” in: Journal of Historical Sociology 34 (2021), vol. 2, (pp.). 350–374, online https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/johs.12336 [16.10.2024]; Ole B. Jensen u.a. (eds.), Handbook of Urban Mobilities (London: Routledge, 2020).

[7] There is therefore a proposal to distinguish between the movement (mobility) and the possibility thereof (motility): Vincent Kaufmann, Re-Thinking Mobility. Contemporary Sociology (Aldershot: Routledge, 2002).

[8] See Gianenrico Bernasconi/Ueli Haefeli/Hans-Ulrich Schiedt, “Editorial. Mobilität. Ein neues Konzept für eine alte Praxis,” in: Traverse 3 (2020), (pp.) 7–11, here (p.) 7f., online https://www.chronos-verlag.ch/node/27688 [16.10.2024].

[9] Eike-Christian Heine/Christian Zumbrägel, “Technikgeschichte,” Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 20.12.2018, http://docupedia.de/zg/Heine_zumbraegel_technikgeschichte_v1_de_2018 [16.10.2024].

[10] See Ueli Haefeli, “Die Entdeckung der Mobilität in der Verkehrswissenschaft. Fachdiskurse in Deutschland und der Schweiz nach 1970,” in: Traverse 3 (2020), (pp.) 17–31, here (p.) 22, online https://www.chronos-verlag.ch/node/27688 [16.10.2024].

[11] An excellent example of air transport and racism in the USA is provided by: Anke Ortlepp, Jim Crow Terminals. The Desegregation of American Airports (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017). See also Colin Pooley, “Mobility, Transport and Social Inclusion. Lessons from History,” in: Transport Policy and Social Inclusion 4 (2016), vol. 3, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v4i3.461 [16.10.2024].

[12] See for example Ted Finlayson-Schueler, “Transport,” in: Susan Burch/Paul K. Longmore (eds.), Encyclopedia of American Disability History (New York: Facts on File, 2009), (pp.) 906-908. On the history of disability in general: Gabriele Lingelbach/Sebastian Schlund, “Disability History,” Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 08.07.2014, http://docupedia.de/zg/lingelbach_schlund_disability_history_v1_de_2014 [16.10.2024].

[13] However, immobility can also be a factor for social advancement, for example if experience abroad is given less weight than solid local networks; see Noel Salazar, “Immobility. The relational and experiential qualities of an ambiguous concept,” in: Transfers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Mobility Studies 11 (2022), vol. 3, (pp.) 3–21, here (p.) 13. On educational mobility: Isabella Löhr, Globale Bildungsmobilität 1850-1930. Von der Bekehrung der Welt zur globalen studentischen Gemeinschaft (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2021). On the connection between spatial, transnational mobility and social mobility from a sociological perspective, see Thomas Faist, “The Mobility Turn. A New Paradigm for the Social Sciences?”, in: Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (2013), vol. 11, (pp.) 1637–1646.

[14] See Colin Divall, “Mobilities and Transport History,” in: Peter Adey et al. (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Mobilities (New York: Routledge, 2017), (pp.) 36–44, her (p.) 40. Divall states that the history of mobility is strongly dominated by topics of personal mobility, while goods, waste, raw materials, etc. are neglected. This relationship was better balanced in the older transportation history.

[15] An overview of the corresponding charts and figures can be found at: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, “Globalisierung”, 01.10.2018, https://www.bpb.de/nachschlagen/zahlen-und-fakten/globalisierung/ [16.10.2024].

[16] See Rolf Peter Sieferle, “Transport und Wirtschaftliche Entwicklung,” in: id. (ed.), Transportgeschichte (Berlin: Lit, 2008), (pp). 1–38, here (p.) 35.

[17] See Christoph Maria Merki, Verkehrsgeschichte und Mobilität (Stuttgart: UTB, 2008), (pp.) 55f., 66–69.

[18] Kurt Möser, “Prinzipielles zur Transportgeschichte,” in: Rolf Peter Sieferle (ed.), Transportgeschichte, (pp.) 39–78, here (p.) 40. Rejecting the concept of revolution because it obscures longer-term processes: Hans-Ulrich Schiedt, “Einführung zu den Beiträgen zur Verkehrsgeschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts,” in: Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte 25 (2010), pp. 151–153.

[19] On this dematerialization, see Roland Wenzlhuemer, Mobilität und Kommunikation in der Moderne (Göttingen: UTB, 2020), (pp.) 60–76.

[20] Jürgen Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung der Welt. Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts (München: Beck, 2009), (p.) 1011.

[21] Stefanie Gänger/Jürgen Osterhammel, “Denkpause für Globalgeschichte,” in: Merkur 74 (2020), vol. 855, (pp.) 79–86, here (p.) 81.

[22] Merki, Verkehrsgeschichte, (p.) 76. In his introductory book, Merki makes interesting suggestions as to how this narrative of increase can be critically examined, for example, through gender, social and environmental perspectives.

[23] See Kerilyn Schewel, “Understanding Immobility. Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies,” in: International Migration Review 54 (2020), vol. 2, (pp.) 328–355, online https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0197918319831952 [16.10.2024].

[24] Sebastian Conrad, Globalgeschichte. Eine Einführung (München: Beck, 2013), (p.) 27.

[25] For a German-German comparison, see Christopher Kopper, Handel und Verkehr im 20. Jahrhundert (München: Oldenbourg, 2002), (pp.) 69, 75. Furthermore: Axel Doßmann, Begrenzte Mobilität. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Autobahnen in der DDR (Essen: Klartext, 2003); Luminita Gatejel, Warten, hoffen und endlich fahren. Auto und Sozialismus in der Sowjetunion, in Rumänien und der DDR (1956–1989/91) (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus, 2014); Barbara Schmucki, Der Traum vom Verkehrsfluß. Städtische Verkehrsplanung seit 1945 im deutsch-deutschen Vergleich (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus, 2001).

[26] For general information on inequality and mobility, see: Mimi Sheller, Mobility Justice. The Politics of Movement in an Age of Extremes (New York: Verso Books, 2018); Julia Leyda, American Mobilities. Geographies of Class, Race, and Gender in US Culture (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016).

[27] See Merki, Verkehrsgeschichte, (p.) 31.

[28] See for example Beate Althammer, Vagabunden. Eine Geschichte von Armut, Bettel und Mobilität im Zeitalter der Industrialisierung (1815–1933) (Essen: Klartext, 2017); Leo Lucassen, “Eternal Vagrants? State Formation, Migration and Travelling Groups in Western Europe 1350–1914,” in: Leo Lucassen/Jan Lucassen (eds.), Migration, Migration History, History. Old Paradigms and New Perspectives (Bern: Peter Lang, 1997), (pp.) 225–251. On colonial contexts, see Valeska Huber, “Multiple Mobilities. Über den Umgang mit verschiedenen Mobilitätsformen um 1900,” in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 36 (2010), vol. 2, (pp.) 317–341, here (pp.) 328–330.

[29] See Thede Kahl, “Auswirkungen von neuen Grenzen auf die Fernweidewirtschaft Südosteuropas,” in: Cay Lienau (ed.), Raumstrukturen und Grenzen in Südosteuropa (München: Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft, 2001), (pp.) 245–271.

[30] Representative works from the wealth of research literature include Anita Böcker (ed.), Regulation of Migration. International Experiences (Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis Publishers, 1998); Julia Devlin/Tanja Evers/Simon Goebel (eds.), Praktiken der (Im-)Mobilisierung. Lager, Sammelunterkünfte und Ankerzentren imKontext von Asylregimen (Bielefeld: transcript, 2021); Andreas Fahrmeir, Citizens and Aliens. Foreigners and the Law in Britain and the German States, c. 1789–1870 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2000); Christiane Reinecke, Grenzen der Freizügigkeit. Migrationskontrolle in Großbritannien und Deutschland, 1880–1930 (München: Oldenbourg, 2010); John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport. Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (New York/Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

[31] See the traffic figures from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), https://www.icao.int [16.10.2024].

[32] See Jan Lucassen/Leo Lucassen, “The Mobility Transition Revisited, 1500–1900. What the Case of Europe Can Offer to Global History,” in: Journal of Global History 4 (2009), (pp.) 347–377.

[33] Steve Hochstadt, Mobility and Modernity. Migration in Germany 1820–1989 (Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1999), (pp.) 217ff, 276f. See also Karl Schwarz, Analyse der räumlichen Bevölkerungsbewegung (Hannover: Jänecke, 1969).

[34] Silke Göttsch-Elten, “Mobilitäten – Alltagsperspektiven, Deutungshorizonte und Forschungsperspektiven,” in: Reinhard Johler/Max Matter/Sabine Zinn-Thomas (eds.), Mobilitäten. Europa in Bewegung als Herausforderung kulturanalytischer Forschung (Münster: Waxmann, 2011), (pp.) 15–29, here (p.) 29.

[35] Mimi Sheller, “Theorising Mobility Justice,” in: Tempo Social. Revista de Sociologia da USP 30 (2018), vol. 2, (pp.) 17–34, here (p.) 20.

[36] See Kevin Hannam/Mimi Sheller/John Urry, “Editorial. Mobilities, Immobilities and Moorings,” in: Mobilities 1 (2006), vol. 1, (pp.) 1–22, online https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/17450100500489189?needAccess=true [16.10.2024].

[37] Sheller, Theorising, (p.) 20.

[38] Also the basic text of Mobility Studies: Mimi Sheller/John Urry, “The New Mobilities Paradigm,” in: Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38 (2006), vol. 2, (pp.) 207–226, here (p.) 208, online https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/122109/mod_resource/content/1/The%20new%20mobilities%20paradigm%20Sheller%20-%20Urry.pdf [16.10.2024].

[39] Tim Cresswell, On the Move. Mobility in the Modern Western World (London: Routledge, 2006), (p.) 1f.

[40] Sheller/Urry, New Mobilities Paradigm, S. 212. A historiographical look at the term can be found in: Huber, Multiple Mobilities. On the original concept: Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, “Multiple Modernities. Analytical Framework and Problem Definition,” in: Thorsten Bonacker/Andreas Reckwitz (eds.), Kulturen der Moderne. Soziologische Perspektiven der Gegenwart (Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus, 2007), (pp.) 19–45.

[41] Sheller, Mobility Justice, (p.) 22.

[42] See Peter Adey, Mobility (London/New York: Routledge, 2010), (p.) 17f.

[43] See Peter Adey, “If Mobility is Everything Then it is Nothing. Towards a Relational Politics of (Im)mobilities,” in: Mobilities 1 (2006), vol. 1, (pp.) 75–94.

[44] See Tim Cresswell, “The Production of Mobilities,” in: New Formations 43 (2001), vol. 1, (pp.) 1–25.

[45] See Nikhil Anand/Akhil Gupta/Hannah Appel (eds.), The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 2018).

[46] See Tim Cresswell, “Towards a Politics of Mobility,” in: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (2010), (pp.) 17–31; Adey, Mobility, (p.) 83ff.

[47] See Peter Merriman, “Mobilities, Crises, and Turns. Some Comments on Dissensus, Comparative Studies, and Spatial Histories,” in: Mobility in History 6 (2015), (pp.) 20–34; Peter Merriman, Mobility, Space and Culture (New York: Routledge, 2012), (p.) 13. For criticism see also: Javier Caletrío, “The New Mobilities Paradigm – by Mimi Sheller and John Urry,” in: Forum Vies Mobiles/Mobile Lives Forum, 11.12.2012, https://forumviesmobiles.org/en/essential-readings/501/new-mobilities-paradigm-mimi-sheller-and-john-urry [16.10.2024].

[48] In general on new turns and the criticism of such intellectual trendsetting: Doris Bachmann-Medick, “Cultural Turns,” Version: 2.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 17.06.2019, http://docupedia.de/zg/Bachmann-Medick_cultural_turns_v2_de_2019 [16.10.2024].

[49] For a review of the genesis and impact of the New Mobilities Paradigm: Mimi Sheller/John Urry, “Mobilizing the New Mobilities Paradigm,” in: Applied Mobilities 1 (2016), vol. 1, (pp.) 10–25.

[50] Huber, Multiple Mobilities, (p.) 317.

[51] The following sections by no means cover all historical fields of research in which mobility studies are currently being received. For example, corresponding approaches can also be found sporadically in social, gender, and family history. See for example: Claudia Roesch, “Nach Belgrad, London oder Den Haag. Abtreibungsreisen westdeutscher Frauen in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren,” in: Ariadne. Forum für Frauen- und Geschlechtergeschichte 77 (2021) (pp.) 122–137, on Mobility Studies at (p.) 126.

[52] Möser, Transportgeschichte, (p.) 39.

[53] Merki, Verkehrsgeschichte, (p.) 10.

[54] See Kopper, Handel und Verkehr, (p.) 84.

[55] See Hans-Liudger Dienel, “Verkehrsgeschichte auf neuen Wegen,” in: Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 48 (2007), vol. 1, (pp.) 19–37, here (p.) 19.

[56] See David A. Turner, “Introduction,” in: id. (ed.), Transport and its Place in History. Making the Connections (New York: Routledge, 2020), (pp.) 1–12. On the history of transport in Germany, see Kopper, Handel und Verkehr, (p.) 83.

[57] Divall, Mobilities and Transport History, (p.) 37.

[58] Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Geschichte der Eisenbahnreise. Zur Industrialisierung von Raum und Zeit im 19. Jahrhundert, (München: Hanser, 1977); Jeffrey Richards/John M. Mackenzie, The Railway Station. A Social History (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1986).

[59] Anette Schlimm, Ordnungen des Verkehrs. Arbeit an der Moderne – deutsche und britische Verkehrsexpertise im 20. Jahrhundert (Bielefeld: transcript, 2011), (p.) 23.

[60] Cotten Seiler, Republic of Drivers. A Cultural History of Automobility in America (Chicago: The Univ. of Chicago Press, 2008), (p.) 11f. Automobility is a defining topic of mobility studies. For repercussions on historical automotive research, especially in Latin America but also beyond, see: Mario Peters, “Automobilität in Lateinamerika. Eine historiographische Analyse,” in: Jahrbuch für die Geschichte Lateinamerikas 56 (2019), (pp.) 369–395, in particular (p.) 373f., online https://journals.ub.uni-koeln.de/index.php/jbla/article/view/1751 [16.10.2024].

[61] Gijs Mom, “The Crisis of Transport History: A Critique, and a Vista,” in: Mobility in History 6 (2015), vol. 1, (pp.) 7–19.

[62] For example, the social and cultural history study by: Sina Fabian, Boom in der Krise. Konsum, Tourismus, Autofahren in Westdeutschland und Großbritannien 1970–1990 (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2016); also: Annette Vowinckel, Flugzeugentführungen. Eine Kulturgeschichte (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2011).

[63] Siehe Anke Hertling, Eroberung der Männerdomäne Automobil. Die Selbstfahrerinnen Ruth Landshoff-Yorck, Erika Mann und Annemarie Schwarzenbach (Bielefeld: Aisthesis, 2013); Anne-Katrin Ebert, “Liberating Technologies? Of Bicycles, Balance and the “New Woman” in the 1890s,” in: Icon 16 (2010), (pp.) 25–52; Anne-Katrin Ebert, Radelnde Nationen. Die Geschichte des Fahrrads in Deutschland und den Niederlanden bis 1940 (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus, 2010).

[64] See Uwe Fraunholz, Motorphobia. Anti-automobiler Protest in Kaiserreich und Weimarer Republik (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2002); Peter D. Norton, “Street Rivals. Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street,” in: Technology and Culture 48 (2007), vol. 2, (pp.) 331–359; Shawn W. Miller, “Automotive Enclosures. The ‘Nature’ of Rio de Janeiro’s Streets and the Elite Domination of the Urban Commons, 1900-1960,” in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 14 (2017), (pp.) 487–510, https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/3-2017/5523 [16.10.2024]; Kurt Möser, “The Dark Side of ‘Automobilism’, 1900–30. Violence, War and the Motor Car,” in: The Journal of Transport History 24 (2003), vol. 2, (pp.) 238–258; Mario Peters, “Desastre! Accidents, Traffic Conflicts, and U.S. Influence in the Construction of Automobile Hegemony in Brazil, 1910-1930,” in: Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 45 (2020), vol. 1, (pp.) 104–121.

[65] See Dirk van Laak, Infrastrukturen, Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 01.12.2020 http://docupedia.de/zg/laak_infrastrukturen_v1_de_2020 [16.10.2024]. Specifically on mobility-related exclusion: Tobias Kuttler/Massimo Moraglio (eds.), Re-thinking Mobility Poverty. Understanding Users' Geographies, Backgrounds and Aptitudes (London: Routledge, 2020).

[66] See for example Jonathan Holst, “Das Machen von Nicht-Orten,” in: Nils Güttler/Niki Rhyner/Max Stadler (eds.), Flughafen Kloten. Anatomie eines komplizierten Ortes, Æther #1 (Zürich: intercom, 2018), online https://aether.ethz.ch/ausgabe/flughafen-kloten/ [16.06.2024]. Homeless people and their scope for action in airports is also the subject of a chapter in the as yet unpublished Habilitation thesis by Britta-Marie Schenk „Ohne Unterkunft? Eine Geschichte der Obdachlosigkeit im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert”.

[67]Barbara Lüthi, The Freedom Riders Across Borders. Contentious Mobilities (London/New York: Routledge, 2023).

[68] For the debate, especially between Gijs Mom and Peter Merriman, see the “Polemics” section in: Mobility in History 6 (2015), vol. 1, (pp.) 7–39.

[69] Also noted by: Dienel, Verkehrsgeschichte, (p.) 32.

[70] Reiner Ruppmann, “‘Transport-, Verkehrs- und Mobilitätsgeschichte’ oder ‘Mobilität in der Geschichte’? Zur Diskussion über Methoden und Profilierung eines Forschungsfeldes,” in: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte 103 (2016), vol. 2, (pp.) 201–208, here (p.) 207.

[71] Turner, Introduction, (pp.) 1–12. Michael Freeman also spoke out in favor of plurality and against an overly general call for a cultural turn in transport history: Michael Freeman, “‘Turn If You Want To’. A Comment on the ‘Cultural Turn’ in Divall an Revill’s ‘Cultures of Transport’,” in: Journal of Transport History 27 (2006), vol. 1, (pp.) 138–143.

[72] Anne-Katrin Ebert, “Mobilität(en) – ein neues Paradigma für die Verkehrsgeschichte?”, in: NTM. Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 23 (2015), (pp.) 87–107.

[73] Dirk van Laak, Alles im Fluss. Die Lebensadern unserer Gesellschaft – Geschichte und Zukunft der Infrastruktur (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2018), (pp.) 211–220.

[74] See Jörg Potthast, Die Bodenhaftung der Netzwerkgesellschaft. Eine Ethnografie von Pannen an Großflughäfen (Bielefeld: transcript, 2007). Monika Dommann takes a similar approach, assuming standstill, in: Monika Dommann, Materialfluss. Eine Geschichte der Logistik an den Orten ihres Stillstands (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2023).

[75] Van Laak, Alles im Fluss, p. 12.

[76] Ueli Haefeli, “Die Entdeckung der Mobilität in der Verkehrswissenschaft. Fachdiskurse in Deutschland und der Schweiz nach 1970,” in: Traverse 3 (2020), (pp.) 17–31, here (p.) 22. See also: Mimi Sheller, “Sustainable Mobility and Mobility Justice. Towards a Twin Transition,” in: Margaret Grieco/John Urry (eds.), Mobilities. New Perspectives on Transport and Society (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), (pp.) 289–304.

[77] Christopher Neumaier/Helmuth Trischler/Christopher Kopper, “Visionen – Räume – Konflikte. Mobilität und Umwelt im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert,” Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 14 (2017), vol. 3, (pp.) 403–419, https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/3-2017/5513 [16.10.2024]; Tom McCarthy, Auto Mania. Cars, Consumers, and the Environment (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 2007).

[78] See Arnaud Passalacqua, “The Carbon Footprint of a Scientific Community. A Survey of the Historians of Mobility and their Normalized yet Abundant Reliance on Air Travel,” in: The Journal of Transport History 42 (2021), vol. 1, (pp.) 121–141; Francesca Falk, “Wir brauchen eine Migrantisierung der Geschichtsschreibung – und eine Mobilitätskritik,” in: Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte 69 (2019), vol. 1, (pp.) 146–163, here at pp. 160–163, online https://www.sgg-ssh.ch/sites/default/files/szg_pdf/009_falk_szg_1_2019.pdf [16.10.2024]. See also the paper discussed at the 2021 Historikertag: Reinhild Kreis/with Frank Bösch/Martina Winkler/Benjamin Beuerle, Nachhaltige Internationalisierung: Wissenschaft und Reisen, podium discussion on 06.10.2021, https://www.historikerverband.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/vhd_journal_2020-09_screen.pdf [16.10.2024].

[79] See Kurt Möser, “Historische Zukünfte des Verkehrs,” in: Ralf Roth/Karl Schlögel (eds.), Neue Wege in ein neues Europa. Geschichte und Verkehr im 20. Jahrhundert (Frankfurt a.M.: Campus, 2009), (pp.) 391–414; Gijs Mom, The Electric Vehicle. Technology and Expectations in the Automobile Age (Baltimore/London: The Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2004). See also Heine, Zumbrägel, Technikgeschichte.

[80] See Ruth Oldenziel/Helmuth Trischler (eds.), Cycling and Recycling. Histories of Sustainable Practices (New York: Berghahn, 2016). The Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society at the LMU Munich, which is headed by Helmuth Trischler, stands for such innovative combinations of mobility and environmental history.

[81] A good introduction to the intersection of environmental and mobility history, which also highlights this differentiation, is provided by: Ben Bradley/Jay Young/Colin M. Coates, “Introduction,” in: id. (eds.), Moving Natures. Mobility and the Environment in Canadian History (Univ. of Calgary Press, 2016), (pp.) 1–22, in particular pp. 9–13; Thomas Zeller, “Editorial. Histories of Transport, Mobility and Environment,” in: The Journal of Transport History 35 (2014), vol. 2, (pp.) iii–v. See also Gijs Mom on “Environmental Mobility History in the Making”, Carson Fellow Portraits, Marta Niepytalska and Alec Hahn, September 2010, at YouTube: https://youtu.be/oLdMSY6bHPk [16.10.2024].