Schriftzug MENSCH, Frankfurt a.M. 2018. Foto: Kai-Britt Albrecht, Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

1. Einleitung

„Jetzt schießen, mit und ohne Komfort, / die Biographien aus dem Boden hervor: / Kaiser Gustav der Heizbare; Fürstenberg; / der Herzbesitzer von Heidelberg; / […] / sie alle bekommen ihre Biographie / (mit Bild auf dem Umschlag) – jetzt oder nie! / Heute so dick wie ein Lexikon, / und morgen spricht kein Mensch mehr davon.“[1]

Kurt Tucholsky bezog sich mit diesem ironischen Gedicht 1927 auf die (auch) im deutschsprachigen Raum hitzig geführte Debatte zwischen den Vertreter:innen wissenschaftlicher und populärer historischer Biografien. Diese Diskussion um Biografien hat ebenso wenig an Aktualität verloren wie Biografien selbst. Für die Geschichtswissenschaft im Allgemeinen und die Zeitgeschichte im Besonderen ist das Genre Biografie ein bedeutender Ansatz: In den letzten Jahren ist eine Vielzahl historischer Biografien erschienen, während die jüngste Konjunktur von interdisziplinären theoretischen und methodischen Diskussionen begleitet wird.

In neueren Forschungstexten werden Biografien definiert als die „Präsentation und Deutung eines individuellen Lebens innerhalb der Geschichte“,[2] als „individuelle Lebensgeschichte, die sowohl den äußeren Lebenslauf als auch die geistige und psychische Entwicklung umfasst“,[3] oder als „textuelle Repräsentation eines Lebens“, in der „immer eine reale Person“ im Zentrum steht. Biografien sind damit sogenannte Wirklichkeitserzählungen.[4] Die Historikerin Cornelia Rauh hat anschaulich beschrieben, dass es „um die geschichtswissenschaftlichen Bemühungen [geht], das Verhältnis von Individuum und Gesellschaft zu reflektieren, und um die Relevanz, die ‚den wirklichen Menschen‘ – bedeutenden und gewöhnlichen, bekannten und unbekannten, Männern und Frauen – im historischen Prozess darstellerisch und durch theoretische Reflexion beigemessen wurde“.[5]

So verstanden, bezeichnen Biografien im engeren Sinne weder die eigene Lebenserzählung (Autobiografie, Memoiren) noch Texte, die die Bezeichnung für leblose Objekte o.Ä. verwenden.[6] Sowohl im deutsch- als auch englischsprachigen Raum sind in den letzten Jahren lohnende literatur- und geschichtswissenschaftliche Überblickswerke zur Geschichte und Gattung der Biografie erschienen.[7] Biografie ist ein literarisches und wissenschaftliches Genre, das erst durch theoretische und methodische Reflexionen zu einem konzeptionellen Ansatz der Geschichtswissenschaft wird. Mithilfe einer biografischen Perspektive können strukturelle Faktoren, Subjektivierungsprozesse, Handlungsweisen und Motivationen in der Geschichte erforscht werden. Biografie als akteurszentrierte Geschichtsschreibung bietet die Möglichkeit, auf inhaltlicher wie theoretischer Ebene Fragen von Handlungsspielräumen und von Repräsentativität zu diskutieren.

Dieser Beitrag beginnt mit einer Übersicht zur Entwicklung der Biografik in den (deutsch- und englischsprachigen) Geschichtswissenschaften. Anschließend thematisiere ich die Popularität (und Grenzen) des Genres und stelle einige aktuelle Forschungsfelder der Biografik vor, die sich „neuen“ Subjekten und Themen widmen. Nach Hinweisen zum Schreiben von Biografien schließe ich mit dem Plädoyer, durch Biografien Geschichte zu dezentrieren.

2. Geschichte und Biografik

2.1 Debatten und Konjunkturen

Bei Tucholskys Intervention vor hundert Jahren ging es sowohl um das Genre als literarische Kunstform als auch um die Rolle des Individuums in der Geschichte und nicht zuletzt um politische Standpunkte.[8] Akademische Historiker hielten gut verkäufliche historische Biografien für unwissenschaftlich, sahen dadurch die Geschichtswissenschaft gefährdet und nahmen diese Entwicklung als Krise wahr. Dessen ungeachtet wurden auch in den Geschichtswissenschaften weiter Biografien geschrieben.[9]

Die (fachwissenschaftliche) Kritik an populären Biografien führte zu einer fachinternen Diskussion über das Genre, die stetig, wenn auch nicht immer mit gleicher Intensität, fortgesetzt wurde, zunächst besonders im angloamerikanischen Raum und in den letzten 20 bis 30 Jahren ebenso in der deutschsprachigen Geschichtswissenschaft.[10] Noch 70 Jahre nach Tucholsky schätzte der Literaturkritiker Stanley Fish mit ähnlichen Argumenten (nur weniger heiter) das Genre negativ ein: „Biographers […] can only be inauthentic, can only get it wrong, can only lie, can only substitute their own story for the story of their announced subject. […] Biography, in short, is a bad game, and the wonder is that so many are playing it and that so many others are watching it and spending time that might be better spent on more edifying spectacles like politics and professional wrestling.“[11]

Hat sich trotz der kontinuierlichen Debatte über biografisches Erzählen seit früheren Überlegungen – in Großbritannien vor allem vertreten durch Samuel Johnson und James Boswell, im deutschsprachigen Raum zum Beispiel durch Johann Gustav Droysen[12] – somit (zu) wenig verändert? Biografien selbst gibt es schon seit der Antike, über Biografien als Genre wird spätestens seit der Frühen Neuzeit nachgedacht.[13]

Der soziopolitische und kulturelle Wandel nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg führte in deutschsprachigen und anderen europäischen Ländern sowie in den USA zu einer Veränderung des Genres Biografie. Nicht nur in Deutschland erfreuten sich Lebensbeschreibungen großer Beliebtheit, auch in Großbritannien und den USA war die dortige new biography ökonomisch erfolgreich.[14] Diese Richtung wies größere Parallelen zum fiktionalen Schreiben auf und ging von der reinen Beschreibung zur Interpretation des porträtierten Lebens über. Das Zusammenspiel von Leben und Werk, besonders bei Biografien über Schriftsteller:innen, rückte ins Zentrum.[15] Nach diesem Aufschwung in den 1920er-Jahren wurden zwar weiterhin Biografien – oft als Hagiografien – publiziert, das Genre verlor jedoch wissenschaftlich im englisch- und deutschsprachigen Raum an Bedeutung: in den USA durch die Dominanz des literaturwissenschaftlichen Paradigmas new criticism, der Sozialgeschichte und intellectual history, in Deutschland durch die Zäsur des Nationalsozialismus, da Vertreter:innen kulturhistorischer Perspektiven vertrieben, verfolgt, ermordet wurden.

Die ab den 1960er-Jahren dominanten sozialhistorischen Ansätze stellten kollektive gesellschaftliche Strukturen in den Mittelpunkt, während Individuen und ihre Handlungsspielräume als weniger geschichtsmächtig verstanden wurden.[16] Hans-Ulrich Wehler formuliert es so: „Wenn es in der Geschichte sowohl um allgemeine Strukturen und Prozesse einerseits als auch um individuelle Handlungen und Entscheidungen andrerseits geht, […] kann eine Geschichtswissenschaft […] wichtige strukturelle Rahmenbedingungen und prozessuale Entwicklungen herausarbeiten helfen, die an sich wissenswert sind, zugleich aber dem intentionalen Handeln von Einzelnen oder Gruppen schwer überschreitbare Grenzen setzen […].“[17]

Historische Subjekte – das Zentrum von Biografien – verloren daher in den fachwissenschaftlichen Diskussionen im deutschsprachigen Raum zunächst an Bedeutung. Die historischen Sozialwissenschaften führten jedoch zu theoretischen und methodischen Entwicklungen, die ab den 1980er-Jahren die Biografik wiederum positiv beeinflussten, indem Sozialisation und strukturelle Prägungen stärker in die Analyse einbezogen wurden, um zu untersuchen, inwiefern Individuen „die vorgefundenen Strukturen aufgreifen und handelnd reproduzieren oder verändern“.[18]

Während Biografien in den USA im 20. Jahrhundert ein populäres Genre blieben, intensivierten sich auch dort die theoretisch-methodischen Debatten erst seit Ende der 1970er-Jahre wieder und führten u.a. zur langsamen Institutionalisierung der Biografieforschung (siehe Institutionalisierung der Biografieforschung). Es erschienen einflussreiche Sammelbände[19] und Monografien zur Biografik. Leon Edel beispielsweise schlug eine Erneuerung der new biography vor und verband dazu Biografie mit Literaturkritik und einem psychoanalytischen Interpretationsansatz, um das Denken und das Unbewusste des biografierten Subjekts zu verstehen. Zwar war Edels psychologischer Ansatz im angloamerikanischen Raum einflussreich, wurde jedoch gleichzeitig von anderen Biograf:innen kritisiert.[20]

Die Debatten der 1980er-Jahre und die theoretischen Ansätze der Literatur- und Geschichtswissenschaften in den 1990er-Jahren führten in den USA zu einer Pluralisierung der Biografik, wobei besonders poststrukturalistische, feministische und postkoloniale Theorien zum Wandel des Genres beigetragen haben, da „‚Kohärenz‘ und ‚Kontinuität‘ der ‚Person‘ […]“, so Judith Butler, „gesellschaftlich instituierte und aufrechterhaltene Normen der Intelligibilität“ seien.[21] Für die Biografik heißt das: Wenn Individuen nicht mehr (nur) als intentional handelnde Subjekte gesehen werden können und Lebensläufe als Konstruktion begriffen werden, funktioniert die klassische Nacherzählung einer Lebensgeschichte nicht mehr. Diese biografische Illusion hat Pierre Bourdieu schon 1986 dargelegt.[22]

Die Illusion der Biografik betrifft darüber hinaus auch Darstellungsformen und -normen, denn Mechanismen des Genres und seiner Konventionen werden beispielsweise durch die chronologisch erzählte Einzelbiografie reproduziert. Nicht nur die Sozialwissenschaften haben darauf hingewiesen, dass Leben fragmentiert und veränderlich sei, dass Personen auf verschiedenen Feldern unterschiedlich agierten und daher in einem Leben eher von Heterogenität statt Kohärenz auszugehen sei.[23] Der Konstruktionscharakter biografischer Identität wird – zumindest in der Theorie der Biografie – mittlerweile stärker berücksichtigt. So wird kaum noch von einer Kohärenz eines Lebenslaufs ausgegangen, wie Simone Lässig festhält: „Immer mehr Biographen erkennen an, dass ein jedes ‚Leben‘ fragmentiert ist und dass jede Person mehrere veränderliche Rollen in sich vereint und mit diesen auf verschiedenen Feldern jeweils unterschiedlich agiert. Weder die einzelnen Rollen noch die korrespondierenden Felder lassen sich einfach addieren und zu einem kohärenten Ganzen formen; Heterogenität ist vielmehr typisch für jede Persönlichkeit.“[24]

Die seit den 1980er-Jahren geäußerte Kritik am Genre, neue methodische wie theoretische Ansätze und die intensiver geführte wissenschaftliche Debatte[25] haben seitdem die Biografik erweitert. Statt der Darstellung von westlichen, weißen,[26] männlichen Subjekten sollte durch die Präsentation von new subjects die hegemoniale Kultur herausgefordert werden.[27] Dazu müssten, so die kritischen Stimmen zur traditionellen Biografik, zum einen die euro- und ethnozentristischen Perspektiven der Geschichtsschreibung verändert,[28] zum anderen die Analysekategorien „race“, Klasse und Geschlecht einbezogen werden. Diese Diskussionen waren und sind in der Geschichtswissenschaft verbunden mit den Ansätzen der Alltagsgeschichte, Historischen Anthropologie und Geschlechtergeschichte. Natalie Zemon Davis hat diese dezentrierende Geschichtsschreibung anhand ihrer Biografie des „Leo Africanus“ exemplarisch durchgeführt.[29] Auf diese Weise wurde auch die Frage nach der Auswahl der Subjekte von Biografien – also: wer ist einer Biografie „würdig“? – neu beantwortet. Dies war eine Folge des neuen Forschungsinteresses an jenen Menschen, die in der Geschichtswissenschaft bisher kaum eine Rolle gespielt hatten.[30]

Das Genre selbst sei pluralistisch, ist die Historikerin Angelika Schaser überzeugt, und biete sich demzufolge für neue Perspektiven an, um die Vielfalt verschiedener Lebenswege aufzuzeigen. Sie kritisiert zugleich, dass die vorliegenden Studien zu unbekannteren Menschen immer noch von vielen Fachkolleg:innen ignoriert würden:[31] „Geschichtswissenschaftliche Biographien spiegeln bezüglich ihrer Konzeption, ihres geschichtswissenschaftlichen Ansatzes, der Quellenbasis, der Auswahl der als biographiewürdig erachteten Personen als auch bezüglich ihrer Rezeption die Pluralisierung der Geschichtswissenschaft wider. Gleichzeitig wird jedoch die Kanonisierung bedeutender, für die politische Geschichtswissenschaft relevanter Biographien, unbeirrt fortgeschrieben.“[32] Die Geschlechterhierarchie ziehe sich, so Schaser weiter, „wie ein roter Faden durch die Geschichtswissenschaft – und deren Biographik“.[33] Auch deshalb ist die Reflexion des Genres Biografie weiterhin notwendig.

Gleichzeitig konnten die theoretisch-methodischen Debatten seit den Cultural Turns dem Erfolg des Genres wenig anhaben, im Gegenteil: Der Blick auf den populären Buchmarkt ebenso wie auf die wissenschaftlichen Veröffentlichungen in Deutschland und den USA zeigt: Biografien werden in großer Menge geschrieben und verkauft.[34]

Unter Biografie wird meist eine Einzelbiografie verstanden, die durch die Darstellung eines Lebenswegs eine (biografische) Einheit konstruiert und stabilisiert. Viele erfolgreiche Biografien widmen sich den „großen“ Männern der Geschichte.[35] Dass Biografie weiterhin ein männlich dominiertes Genre ist, belegt die Kulturwissenschaftlerin Birgitte Possing mit ihrer Analyse historischer Fachzeitschriften in Europa und den USA: Unter den rezensierten biografischen Studien lag der Anteil von Protagonistinnen 2011 nur bei 15 Prozent, der Autorinnen biografischer Studien bei 28 Prozent, wobei Historikerinnen meistens über Frauen, Historiker noch häufiger über Männer arbeiten, vor allem über politische Persönlichkeiten und Intellektuelle.[36] Das Genre ist jedenfalls von einer „Erschöpfung“ weit entfernt.[37] Die, besonders im deutschsprachigen Raum, immer wieder einmal konstatierte Krise der Biografie lasse sich quantitativ kaum belegen, schreiben u.a. Angelika Schaser und Johanna Gehmacher.[38] Dass gerade Geschlechterhistoriker:innen auf die nicht vorhandene Misere der Biografik hinweisen, deutet auch daraufhin, dass Postulate wie das der Krise, vor allem geäußert von männlichen Biografen, die eigene Bedeutung steigern (sollen).

2.2 Institutionalisierung der Biografieforschung

Begleitet wurden die theoretisch-methodischen Debatten in den letzten Jahrzehnten durch die Etablierung von Forschungszentren und Fachzeitschriften. Den Anfang machte 1976 das (heutige) Center for Biographical Research an der University of Hawai’i at Mānoa mit seinem zwei Jahre später gegründeten Journal „Biography“.[39] Außerdem publiziert die Autobiography Society seit 1985 „a/b: Auto/Biography Studies“, während die Zeitschrift „Life Writing“ seit 2004 existiert.[40] An der City University of New York eröffnete 2008 das Leon Levy Center for Biography, das einen Masterstudiengang anbietet.[41] Im deutschsprachigen Raum gibt das Institut für Geschichte und Biographie der Fernuniversität Hagen seit 1988 die Zeitschrift „BIOS“ heraus,[42] während das Netzwerk Zentrum für Biographik seit 2004 und in Wien der Forschungsverbund Geschichte und Theorie der Biographie seit 2005 (bis 2019 als Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Biographie) das Thema als Forschungsschwerpunkt haben. Auch in den Niederlanden entstand eine Forschungseinrichtung: das 2004 in Groningen gegründete Biografie Instituut.[43] 1999 wurde die International AutoBiography Association gegründet, zu der regionale Verbände in Europa, den Amerikas, in Afrika und im asiatisch-pazifischen Raum gehören.[44] Zudem gibt es die Global Biography Working Group mit Workshops, Publikationen und einem Newsletter.[45] Wie die Zeitschriftentitel und Namen der Fachverbände zeigen, werden Biografien und Autobiografien in der angloamerikanischen Tradition des life writing nicht so scharf voneinander abgegrenzt wie in der deutschsprachigen (Geschichts-)Wissenschaft.[46]

2.3 Vom Reiz des Genres

Neue Subjekte, Fragestellungen, Methoden, Formen veränder(te)n das Genre Biografie und sind gleichzeitig inspirierend für die Geschichtswissenschaft selbst.[47] Biografien sind eine produktive Form der Geschichtsschreibung, weil sie:[48]

- dem „Überdruss an einer Geschichtsschreibung, die über der scharfen Analyse von Strukturen und Prozessen die Menschen als Subjekte ihrer Geschichte ganz aus dem Blick verlor“, begegnen;[49]

- aktuelle Entwicklungen aufgreifen und so auf die „gesellschaftlichen und politischen Umbrüche[n] vor und nach der Jahrhundertwende“[50] reagieren können;

- dem erneuerten Interesse am Subjekt (oder auch: an „neuen“ Subjekten) entgegenkommen, das durch innerdisziplinäre Paradigmenwechsel mitbedingt ist;

- interdisziplinär mit anderen Forschungsrichtungen zu verbinden sind: Sozial- oder Literaturwissenschaften, Geschlechter- oder Migrationsforschung, Postkoloniale Studien, Oral History, Wissenschafts- oder Regionalgeschichte usw.;

- das Individuum in der Gesellschaft, in seinen Handlungsspielräumen und Kontexten darstellen und damit das Verstehen von Subjektivität, Subjekt und Subjektivierung ermöglichen (auch von Selbst- und Fremdbildern); die Wandlungsfähigkeit von Subjekten und deren Grenzen ebenso wie die von Gesellschaft nachzeichnen;

- über Zäsuren und gängige Periodisierungen hinausgehen; gesellschaftliche Funktionen erfüllen sowohl im Hinblick auf vergangene Prozesse (individuelles wie kollektives Gedächtnis) als auch mit Blick auf die Zukunft (Legitimation);

- sich besonders gut dazu eignen, Geschichte/n zu erzählen.

Die Attraktivität des Genres zeigt sich dementsprechend in ganz unterschiedlichen Formaten: Bisher in der Politikgeschichte vernachlässigten Akteur:innen widmet sich beispielsweise Barbara von Hindenburgs Studie über die Abgeordneten des Preußischen Landtags. Carolyn Steedman schreibt die Alltagsgeschichte eines englischen Strumpfstrickers; Sammelbände hinterfragen inhaltlich wie auch durch Kollektivautorschaft den Mythos Danton oder nähern sich unterschiedlichen Facetten des Naturwissenschaftlers und Dissidenten Robert Havemann.[51] Historisch gut recherchierte graphic biographies verbinden nicht nur Text und Bild,[52] sondern reflektieren oft auch das Biografie-Schreiben bzw. -Zeichnen, den Prozess der Auswahl und der (problematischen) Quellenüberlieferung.[53] Außerdem kommen biografisch orientierte Spiel- und Dokumentarfilme,[54] Ausstellungen und künstlerische Auseinandersetzungen, gerade auch im Bereich der (sozialen) Medien, hinzu, die den Vorteil haben, chronologische Hierarchien umgehen zu können.[55] Die Grenzen zwischen diesen Formaten sowie zwischen akademischen, populärwissenschaftlichen, journalistischen oder belletristischen Biografien verwischen zunehmend.

3. Neuere biografische Forschungsfelder

Inner- wie außerhalb der Geschichtswissenschaften wurden und werden historische Biografien recherchiert, geschrieben, publiziert. Als historiografischer Ansatz ist das Genre besonders dann leistungsfähig,[56] wenn es mit aktuellen Fragestellungen und innovativen Methoden verbunden wird, so wie es zurzeit in einigen Subdisziplinen geschieht. Im Folgenden stelle ich – nach der Politikgeschichte – daher Biografik in der postkolonialen, transnationalen und Migrationsforschung, in der Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte und in der Geschlechtergeschichte kurz vor. An diese unterschiedlichen thematischen Perspektiven schließt sich mit der Kollektivbiografik ein methodischer Zugriff an. Die Grenzen zwischen diesen Bereichen sind fließend, zumal viele biografische Studien mehrere Forschungsfelder berühren. Außerdem könnte diese Systematik durch weitere, gegenwärtig produktive, Bereiche der Biografik ergänzt werden: Wissenschaftsgeschichte und intellectual history sowie epochenspezifisch die NS-Forschung und DDR-Geschichte. Eine biografische Erforschung der DDR ist – im Vergleich zu anderen Abschnitten deutscher Geschichte – bisher weniger verbreitet, wird jedoch zunehmend als produktiver Zugang für die ostdeutsche Zeitgeschichte genutzt,[57] denn die „erstaunliche Stabilität der kommunistischen Gesellschaftsordnung und ihr plötzlicher Zusammenbruch sind gerade aus gesellschaftsgeschichtlicher Perspektive ohne Einbezug der Lebensgeschichten ihrer Machthaber nicht zureichend zu erklären“, wie Martin Sabrow schon 2013 hervorhob.[58] Zu den neueren Biografien der Zeit- und DDR-Geschichte gehört unter anderem Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuks zweibändige Studie über Walter Ulbricht.[59]

3.1 Biografien in der Politikgeschichte

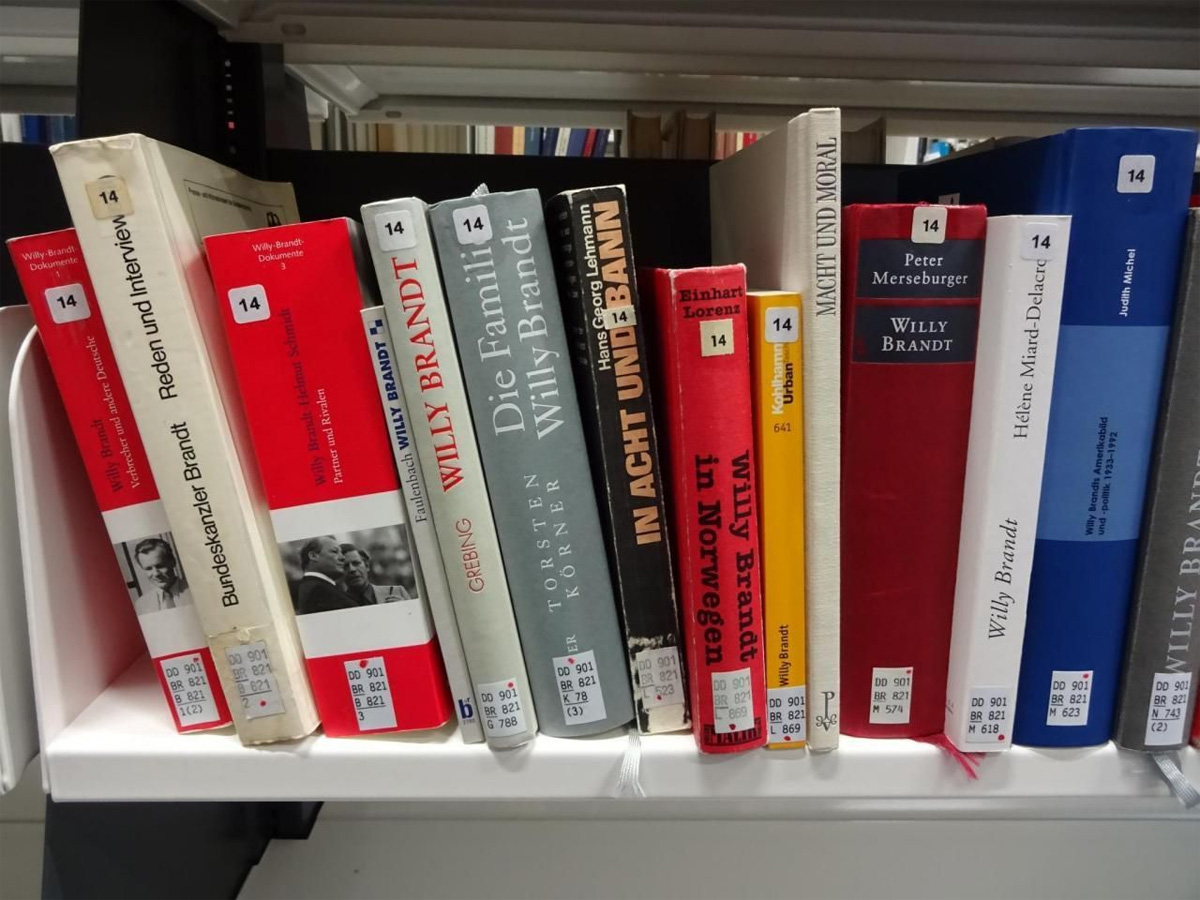

Die deutschsprachige historische Biografik ist im Bereich der Politikgeschichte ein etablierter Ansatz.[60] Politikhistorische Biografien wurden schon mit der Entstehung des Universitätsfachs Geschichte im 19. Jahrhundert ein zentraler Bestandteil der Historiografie und haben seitdem nichts an Popularität eingebüßt. Meist chronologisch erzählt, werden Biografien über Politiker (seltener: über Politikerinnen) zum Beispiel als Zugang genutzt, einen Zeitabschnitt und seine Ereignisse zu erläutern,[61] insbesondere (aber nicht nur) die Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus.[62]

Andere Autor:innen konzentrieren sich auf die Legendenbildung um einen politischen Akteur[63] oder setzen einen Schwerpunkt auf die politisch- intellektuelle Entwicklung des Protagonisten, so zum Beispiel Karl Heinrich Pohl in seiner Studie über Gustav Stresemann. Wie über viele andere Politiker liegen auch über Stresemann diverse Biografien vor, Pohl hingegen verspricht, ein „weitgehend unbekanntes Bild“ zu konstruieren,[64] um mit neuen Ansätzen der Biografieforschung und kulturgeschichtlichen Methoden „das gängige Bild über Stresemann zu bereichern, zu erweitern oder infrage zu stellen“ sowie durch andere Quellen eine Verdichtung und gleichzeitig Dekonstruktionen zu ermöglichen.[65] Statt eines rein teleologisch-chronologischen Aufbaus gliedert Pohl sein Buch entlang der Konzepte kulturelles, soziales, ökonomisches und politisches Kapital nach Pierre Bourdieu, womit er sowohl die sozialen Bedingungen des Werdegangs und des sozialen Aufstiegs – daher der „Grenzgänger“ im Untertitel – als auch die Inszenierungen Stresemanns herausarbeiten kann. Neben Stresemanns Verortung im sozialen Feld nutzt Pohl zudem psychohistorische Überlegungen und bezieht dessen körperlichen Zustand in seine Interpretation ein. Eine Biografie wie diese kann daher für die Zeitgeschichte produktiv sein, indem sie neue Anregungen für aktuelle Forschungsfelder gibt, hier zum Beispiel für die Erforschung der 1920er-Jahre. Zurzeit erscheinen zudem (oft kürzere) Studien über Akteur:innen linker wie rechter politischer Bewegungen und transnationaler Frauenbewegungen, die politische Lebenswege sichtbar machen und zugleich die transnationalen Verflechtungen des politischen Aktivismus rekonstruieren.[66]

Insgesamt wies (teilweise: weist immer noch) gerade die politikhistorische Biografik vor dem Hintergrund der Entwicklung der Nationalstaaten und nationalstaatlich organisierter Forschung zumeist klare nationale Grenzen auf, womit sie sowohl zu einer Reproduktion der imagined communities (Benedict Anderson) als auch zur Stabilisierung von Identität beitrug und beiträgt.[67] Außerdem wiederholen konventionelle politikhistorische Biografien häufig eine geschlechterspezifisch konnotierte Trennung von privat und öffentlich: Frauen werden kaum als Akteurinnen in eigenen Biografien gewürdigt, noch thematisieren Biografien über Politiker Geschlechterverhältnisse; Ehefrauen werden allenfalls als Marginalie kurz erwähnt.[68] Biografien beispielsweise über politische Persönlichkeiten der Dekolonisierung[69] oder über politische Aktivistinnen[70] sind im Vergleich immer noch selten (siehe unten). Und das, obwohl Ernst Pipers Lebensgeschichte Rosa Luxemburgs, wie auch die mehrfach aufgelegte und erweiterte Studie über Queen Victoria von Karina Urbach, zeigen, dass sich wissenschaftlich fundierte, gut lesbare Biografien über Politikerinnen und Regentinnen schreiben und zahlreich verkaufen lassen.[71]

3.2 Transnationale, postkoloniale und Migrationsbiografien

Transnationale, postkoloniale und Migrationsbiografien untersuchen transgressive Lebensläufe, denn Menschen überschritten schon immer Staats-, Sprach- und „Kultur“-Grenzen. Außerhalb der Exilforschung gab es zunächst wenige biografische Studien über mobile Leben.[72] Seit einiger Zeit jedoch inspiriert die globale und postkoloniale Geschichtsschreibung die Biografik. So plädiert der Germanist Hannes Schweiger für eine „Pluralisierung von Lebensgeschichten“ und die „Kosmopolitisierung der Biographik“,[73] um kulturelle Transferprozesse, transnationale Netzwerke und Handlungsspielräume beschreiben zu können. Die Historikerinnen Johanna Gehmacher und Katharina Prager skizzieren unterschiedliche Formen transnationaler Leben, deren Differenzen und Gemeinsamkeiten sowie Machtverhältnisse, Positionierungen und Handlungsspielräume zu reflektieren sind.[74] Die neuere Forschung untersucht Biografien kolonisierender und kolonisierter Subjekte, um imperiale Machtverhältnisse, ihre Akteur:innen, deren koloniale Erfahrungen und – im Sinne einer Verflechtungsgeschichte – globale Transferprozesse zu analysieren.[75] Auch postimperiale wie migrationshistorische Biografien eröffnen „akteurszentrierte Perspektiven auf transnationale und globalgeschichtliche Prozesse“.[76]

Dies gelingt Lisa M. Leff, die transnationale Bewegungen von Menschen, Objekten und Wissen in ihrer Studie über den Historiker Zosa Szajkowski verbindet. Szajkowski, 1911 als polnischsprachiger Jude im russischen Zarenreich geboren, emigrierte 1927 nach Frankreich und flüchtete 1941 vor der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung in die USA. Nachdem er schon in Frankreich begonnen hatte, Judaica zu sammeln, setzte er diese Tätigkeit im und nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg fort, indem er zunächst als US-Soldat im besetzten Deutschland Materialien an das YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York schickte und später in den USA und in Israel mit Beständen aus staatlichen und privaten Einrichtungen Frankreichs handelte, die er teilweise stahl. Leff kombiniert in einer chronologischen Erzählung Historiografie- und Archivgeschichte, die Situation von Judaica in Europa und den USA während des Holocausts und der Nachkriegszeit mit aktuellen Forschungsfragen zu Raubkunst- und Provenienzgeschichte. Der Lebensweg von Szajkowski, der sich 1978 nach einem entdeckten Diebstahl in der New York Public Library das Leben nahm, wird dabei in den Kontext transnationaler Netzwerke von Kolleg:innen und Freund:innen rund um das YIVO eingebettet. Durch diese unterschiedlichen thematischen Verknüpfungen erklärt Leff facettenreich, wie (nicht: ob) aus dem „Buchretter“ ein „Archivdieb“ wurde.[77]

3.3 Biografien in der Geschichte der Arbeit

Ebenso werden in der Geschichte der Arbeit, der Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte biografische Ansätze seit langem als anregend diskutiert.[78] Anders als die Politikgeschichte entwickelt dieser Bereich innovative, vor allem mikrohistorische, Zugänge zu Biografien, können sie doch Theorien testen und unterschiedliche Forschungswerkzeuge bereitstellen.[79] Jürgen Finger schlägt eine mikrohistorische Biografik für die Unternehmensgeschichtsschreibung vor, die Familie und Verwandtschaft als soziale Institutionen, das Privatleben, die Art und Weise des Wirtschaftens („business modes“), aber auch Raum und Temporalität einbezieht.[80] So werden ein durchschnittlicher deutscher mittelständischer Firmeninhaber in der NS- und Nachkriegszeit bzw. mit Beate Uhse ausnahmsweise auch eine Unternehmerin wirtschafts- und kulturhistorisch porträtiert.[81] Oder es stehen Netzwerke im Zentrum, wie bei der Bankiersfamilie Morgan und der Industriellenfamilie Thyssen.[82] Für eine biografische Studie ist letztere insofern ungewöhnlich, als Simone Derix zusätzlich quantitative Methoden zur Quellenauswertung nutzt. Überzeugend kann sie mit einer umfangreichen Netzwerkanalyse die Bedeutung transnationaler Beziehungen für das ökonomische Handeln der Familie interpretieren. Außerdem gelingt es dadurch, den Kreis der Akteur:innen um die weniger bekannten Familienmitglieder, um Finanzberater und Angestellte zu erweitern. Die Geschichte dieser vermögenden transnationalen Familie vom späten 19. Jahrhundert bis in die 1960er-Jahre lässt sich so auch als Geschichte des Kapitalismus lesen.

Neben biografisch orientierter Unternehmensgeschichte besteht die Tradition der Arbeiter:innenbiografie, die durch strukturhistorische Ansätze zwar etwas in den Hintergrund geriet, aber seit einer guten Dekade wieder „im Kommen“ ist.[83] Der Historiker Nick Salvatore nimmt an, dass es in sozial- und arbeitsgeschichtlichen Biografien weniger um Repräsentativität gehe, sondern darum, das Individuum in seinen sozialen Kontexten zu zeigen, nach möglichen Entscheidungsmustern zu fragen und die Arbeitswelt dabei verbunden mit dem Privaten zu denken, also die Intersektionen von Geschlecht, Religion, „race“ einzubeziehen.[84] Als „Geschichte von unten“ wurden bisher häufig (männliche) Führungspersonen porträtiert, zudem folgen viele Biografien in diesem Feld einem Narrativ des weißen Nationalismus, d.h., dass zugunsten einer positiven Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung rassistische Politiken von Führungspersönlichkeiten oder diskriminierende Diskurse ausgeblendet werden.[85]

Da es um soziale Bewegungen geht, die historisch gesehen lange Zeit national organisiert waren, sehen sich Autor:innen von Biografien im Forschungsfeld Geschichte bei der Arbeit mit allgemeineren Problemen der Biografik konfrontiert, nämlich weiterhin sehr nationalstaatlich ausgerichtet zu sein und auf diese Weise Nationalismus möglicherweise zu reproduzieren. Nicht zuletzt deshalb, so die Historiker Mark Hearn und Harry Knowles, seien mehr Biografien in der gesamten Breite von Aktivist:innen bzw. von Arbeiter:innen notwendig, ebenso wie mehr biografische Studien über die spezifischen Geschlechterverhältnisse in der Arbeiterbewegung, um die Bedeutung von Individuen für gesellschaftliche Transformationen darzustellen, und zwar ganz unterschiedlicher Menschen.[86]

3.4 Biografien in der Geschlechtergeschichte

Vielfalt abzubilden – dieses Ziel haben sich grundsätzlich Verfasser:innen von Biografien in der Geschlechtergeschichte gesetzt. Zunächst widmeten sich feministische Biografinnen seit den 1970er-Jahren dem Wieder-Einschreiben von Frauen in die Geschichte. In den 1980er-Jahren wurde daran anschließend, besonders im angloamerikanischen Raum, methodisch und theoretisch die feministische Biografik entworfen.[87] Historikerinnen und Literaturwissenschaftlerinnen erklärten, dass der biografische Kanon nicht nur um Autorinnen und Protagonistinnen erweitert werden müsse, sondern auch Konzeptionen und Arbeitsweisen zu verändern seien.[88] Mit Geschlecht als Kategorie der historischen Analyse[89] werden in Biografien Frauenleben untersucht sowie symbolische und soziale Geschlechterordnungen, Ungleichheiten und Marginalisierung.

Die feministische Biografik hat sich zudem intensiv mit Fragen der Themensetzung, Narration, Zugänglichkeit und Analyse der Quellen sowie dem Verhältnis zwischen Autor:in und Protagonist:in beschäftigt.[90] Daraus resultierte die konzeptionelle und narrative Neuerung, entweder eine radikal subjektive Herangehensweise zu wählen oder im Text explizit die Rolle der Biografin zu diskutieren, denn das betrachtende Subjekt ist immer auch Teil der Betrachtung.[91] Den Weg der „Nachforschungen“ wählt zum Beispiel Hilde Schramm in der Biografie ihrer Lehrerin Dora Lux, die die autobiografische Motivation der Studie nicht verschleiert, sondern produktiv nutzt, sodass eine wissenschaftliche und zugleich emphatische Lebensbeschreibung gelingt.[92]

Die kritische Auseinandersetzung (nicht nur) der feministischen Biografik mit dem Genre machte sowohl die Unmöglichkeit von Objektivität als auch den Konstruktionscharakter von Biografien deutlich. Dabei sind geschlechterhistorische Biografien eng verknüpft mit aktuellen Fragestellungen der Gender Studies und der feministischen Theorie und geben mit ihren theoretisch-methodischen Innovationen und ihrem Interesse an gesellschaftlichen Machtverhältnissen häufig entscheidende Impulse für die historische Biografik.[93] Aktuelle Themenfelder der geschlechterhistorischen Biografik umfassen darüber hinaus beispielsweise transnationale Leben,[94] politische Akteurinnen[95] oder die Konstruktion von Männlichkeit, wie dies Falko Schnicke am Beispiel Johann Gustav Droysens, Maurizio Valsania über Thomas Jefferson oder Julia Voss am Beispiel Charles Darwins untersucht haben.[96]

Geschlechterhistorische Biografieforschung und -praxis wurde außerdem schon früh durch intersektionale Ansätze beeinflusst, die nach Verschränkungen zwischen Differenzkategorien (Geschlecht, „race“, Klasse, Nationalität, Sexualität, Alter, Befähigung / Behinderung, Religion) und nach Machtverhältnissen fragen.[97] Intersektionale Biografik erforscht nicht nur marginalisierte Subjekte, sondern auch strukturelle Privilegien – ein Aspekt, der in der konventionellen Biografik bisher vernachlässigt wurde.

Produktiv ist auch die Verknüpfung von Biografien mit LGBTIQ*-[98] und queerer Geschichte, der die Möglichkeit inhärent sein kann, Vorstellungen eines „einheitlichen“ Subjekts infrage zu stellen.[99] Obwohl auto/biografische Zugänge schon für die frühe Sexualforschung eine große Rolle gespielt haben, steht die systematische „Beforschung von queerness, also etwa geschlechtlicher Nonkonformität, Sexualitäten jenseits der Heterosexualität, trans* Männlichkeiten/Weiblichkeiten oder Intergeschlechtlichkeit“ in der Biografik noch aus, wie Joris Atte Gregor festhält. Die Konstruktion heteronormativer Zweigeschlechtlichkeit kann ebenso biografisch analysiert werden, wie sich queere Biografik „gegen normative Zuschreibungen von Identität stellen und neue Formen des Wissens produzieren“ kann.[100] Die Politik- und Sozialwissenschaftlerin Christiane Leidinger beispielsweise zeichnet den Lebens- und Berufsweg der lesbischen Aktivistin und Schriftstellerin Johanna Elberskirchen nach, Laurie Marhoefer rekonstruiert in der Doppelbiografie „Racism and the Making of Gay Rights“ kritisch die Beziehung zwischen Magnus Hirschfeld und Li Shiu Tong.[101] Viele (kollektiv-)biografische Studien verstehen sich zugleich als erinnerungspolitische Interventionen.[102] Ebenso werden biografische Studien im Bereich der Körpergeschichte und/oder der Geschichte der Sexualitäten geschrieben, um vergeschlechtlichte Verkörperungen und Einschreibungen anhand einer Person, Subjektivierungsprozesse oder auch den politischen und wissenschaftlichen Kampf um die Regulierung von Sexualität untersuchen zu können.[103]

3.5 Gruppen- und Kollektivbiografien

Darstellungen von Lebensläufen werden nicht nur als Einzelstudien konzipiert, sondern auch als Gruppen- und Kollektivbiografien.[104] Generell haben diese den Vorteil, auf methodologische Debatten um Repräsentativität zu reagieren, indem sie (häufig) weniger bekannte Lebensläufe darstellen und damit alternative Verläufe von Lebensgeschichten anbieten.[105] „Repräsentativität“ bezieht sich auf die weiter oben schon angesprochenen Fragen danach, wer als einer Biografie würdig erachtet wird und wer nicht – oder anders formuliert: welche Individuen und Gruppen als historische Akteur:innen untersucht und dargestellt werden. Diese Aspekte wurden (und werden) u.a. von der Alltags- und Mikrogeschichte, feministischen Biografik, Rassismus- und de/postkolonialen Forschung aufgeworfen.

Zugleich geht es, besonders in der NS-Forschung, auch darum, die „ganz normalen“ Täter:innen zu untersuchen. 2002 erschienen zwei Studien, die kollektivbiografisches Arbeiten im deutschsprachigen Raum nachhaltig beeinflusst haben: Dorothee Wierling schrieb über den „Jahrgang 1949 in der DDR“ und Michael Wildt über das Führungskorps des Reichssicherheitshauptamtes.[106] Wierling wertet für ihre Kulturgeschichte der DDR u.a. 20 lebensgeschichtliche Interviews aus, um Familie und Erziehung in der Nachkriegszeit, um Politik, Handlungsräume und Wahrnehmungen verschiedener Akteur:innen darzustellen. Wildt hingegen analysiert über 200 Personalakten von NS-Tätern, die Auskunft geben über die generationellen Erfahrungen des Ersten Weltkriegs, Ausbildung, Berufswege sowie Nachkriegskarrieren. Um einzelne Fallstudien ergänzt, gelingt Wildt eine dichte Beschreibung der Institutionen, Akteure und Durchführung der Vernichtungspolitik.

Wie bei Wierling und Wildt konzentrieren sich Kollektivbiografien meist auf einen bestimmten Lebensabschnitt der gewählten Personengruppe, setzen einen thematischen Schwerpunkt oder rücken soziale Interaktionen und Netzwerke in den Mittelpunkt.[107] Denn anhand einer Gruppe lassen sich sowohl Aufstiegs- und Karrieremuster, (familiäre, soziale, intellektuelle) Prägungen, Ungleichheits- und Machtverhältnisse darstellen als auch Besonderheiten und individuelle Spezifika. Daher sind kollektivbiografische Verfahren besonders gut für intersektionale Forschungsfragen geeignet.[108] Unter Gruppen- und Kollektivbiografik fallen unterschiedliche Zugriffe und Formen: Prosopografien, die mit großen Samples und quantitativen Methoden arbeiten,[109] Doppelbiografien[110] und Biografien kleinerer oder größerer Gruppen, die sich als solche selbst konstituierten oder durch die:den Biograf:in konstruiert werden.[111]

Eine Kollektivbiografie, die die Gruppe als solche herstellt, ist zum Beispiel Diana Miryong Natermanns Arbeit über koloniale Akteur:innen aus Europa im sogenannten Kongo Freistaat und in Deutsch-Ostafrika, die Rassismus-, Geschlechter- und Kolonialgeschichte verknüpft. Demgegenüber forscht Christa Wirth über mehrere Generationen einer transnationalen Familie, also über ein Kollektiv, das sich selbst als solches begreift. Wirth kombiniert in dieser Kollektivbiografie Migrations- und Familiengeschichte. Beide Studien beruhen vor allem auf Egodokumenten und bringen durch die kritische Analyse dieser Quellen und ihre innovativen Ansätze neue Perspektiven in die Kollektivbiografik ein.[112] Entlang eines kollektivbiografischen Zugangs kann auch (National-)Geschichte anders und neu erzählt werden, um bisher marginalisierte Akteur:innen sichtbar zu machen.[113]

Kollektivbiografische Ansätze werden in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte seit längerem verwendet, auch verbunden mit geschlechterhistorischen Fragestellungen.[114] Dabei stehen stärker prosopografische Ansätze[115] neben Studien, die Gelehrte (in Einzelkapiteln) über ein biografisch verbindendes Element untersuchen, wie Onur Erdur, der die (post-)kolonialen Kontexte des französischen poststrukturalistischen Denkens rekonstruiert.[116] Ein konventioneller, allerdings neu konzipierter Zugriff der Kollektivbiografie sind Familienbiografien. Standen bisher vor allem Familien bedeutender Künstler:innen oder Herrscher- und Unternehmerfamilien im Fokus dieser kollektiven Biografieschreibung, werden Familienbiografien nun mit aktuellen Fragestellungen verknüpft. So analysiert Alexa von Winning anhand einer russischen Adelsfamilie das Imperium als Familienangelegenheit oder konzipiert Erich Keller in seiner Studie über die Familie Wyler-Bloch „Biografie als Erinnerungsraum“.[117]

Eine bemerkenswerte transnationale Familienbiografie erzählen Rebecca J. Scott und Jean M. Hébrard für die Familie Vincent/Tinchant, die von einer versklavten Frau auf Haiti um 1800 über globalen Zigarrenhandel um 1900 bis zum belgischen Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus reicht, oder Maiken Umbach und Scott Sulzener, die die privaten Fotoalben der Familie Salzmann analysieren, um sowohl die Herstellung nationaler Identitäten in Deutschland und den USA als auch die Erfahrung nationalsozialistischer Verfolgung, Flucht und Exil sichtbar zu machen.[118] Besonders im Bereich der Familiengeschichte zeichnet sich in den letzten Jahren der Trend ab, dass Autor:innen mit einem autobiografischen Zugriff die Biografie/n der eigenen Familie erforschen, sei es über die industrielle Revolution in England, die jüdische Arbeiterbewegung in Osteuropa oder die Migration aus der Türkei nach Westdeutschland.[119]

4. Leben erfinden? – Biografie schreiben!

Die Übersicht verdeutlicht, dass neuere Biografien – seien sie Individual- oder Kollektivstudien – zumeist einen zeitlichen und/oder inhaltlichen Schwerpunkt setzen.[120] Dieser Fokus ist bereits für die biografischen Recherchen außerordentlich relevant und schlägt sich ebenso in der Konzeption und dem Narrativ der Biografie nieder. Einige Biografien machen die biografische Darstellung selbst zum Thema, so Mark Roseman in seiner Studie über Marianne Strauß-Ellenbogen, die als Jüdin die NS-Zeit im Untergrund überlebte. Ähnliches gilt für den „Orientalisten“ des US-amerikanischen Biografen Tom Reiss, der seine abenteuerliche Spurensuche nach der pluralen und fragmentierten Persönlichkeit des Juden Lev Nussimbaum beschreibt, der zum Muslim Essad Bey wurde und als Schriftsteller Kurban Said Erfolge verzeichnete.[121]

Ein preisgekröntes Werk, das viele der neueren methodisch-theoretischen Überlegungen umsetzt, ist Barbara Stollberg-Rilingers „postheroische“ Biografie über Maria Theresia.[122] Stollberg-Rilinger dekonstruiert die nationalstaatlichen Hagiografien über die Herrscherin, indem sie sich „die Heldin vom Leibe“ hält,[123] Maria Theresia und ihre Zeit als uns fremd versteht. Stattdessen wählt die Biografin eine multiperspektivische Narration, die zugleich den Konstruktionscharakter sichtbar macht. Stollberg-Rilinger zeigt, dass sowohl die zeitgenössische Performanz und Inszenierung Maria Theresias als Regentin und Mutter wie auch die spätere Legendenbildung als Ausnahmeherrscherin von binären Geschlechteridealen geprägt war, selbst wenn das höfische Europa im 18. Jahrhundert mit Geschlechterdifferenzen „spielte“. Indem sie Familie, höfische Kultur, Krieg, Reformen, Körperpolitik, Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmungen miteinander kombiniert, bettet Stollberg-Rilinger mikrohistorische Einsichten in den größeren Kontext sozialer und politischer Ereignisse und Strukturen ein: „Das Ziel ist, die Gestalt Maria Theresias in ihrer Zeit zu verstehen – und umgekehrt, die Zeit pars pro toto durch diese Gestalt zu erschließen.“[124]

Wer biografisch arbeitet, muss also eine Vielzahl methodischer, theoretischer, analytischer Vorentscheidungen treffen sowie über Darstellung und Narration nachdenken – möglicherweise noch genauer als bei anderen wissenschaftlichen Studien.[125] Zu den Vorüberlegungen biografischen Arbeitens gehören ganz unterschiedliche Fragen und Aspekte: Was ist überhaupt eine Biografie oder was verstehe ich darunter? Warum arbeite ich biografisch? Zentral ist natürlich die Auswahl des biografischen Subjekts oder der biografischen Subjekte:[126] Über wen schreibe ich und warum? Die gewählte/n Person/en muss/müssen nicht unbedingt repräsentativ oder typisch sein, sie können auch für sich stehen, so oder so sollte die Auswahl gut begründet sein. Wie alle historischen Studien sollte eine Biografie sich ebenfalls an einem thematischen Schwerpunkt und einer erkenntnisleitenden Forschungsfrage orientieren.[127] Ein dezidierter Fokus kann dazu beitragen, ein ausschließlich lineares Narrativ aufzubrechen.[128] Dazu gehört auch, deutlich zu machen, welche theoretischen Vorannahmen bestehen und welcher methodische Ansatz warum gewählt wird.

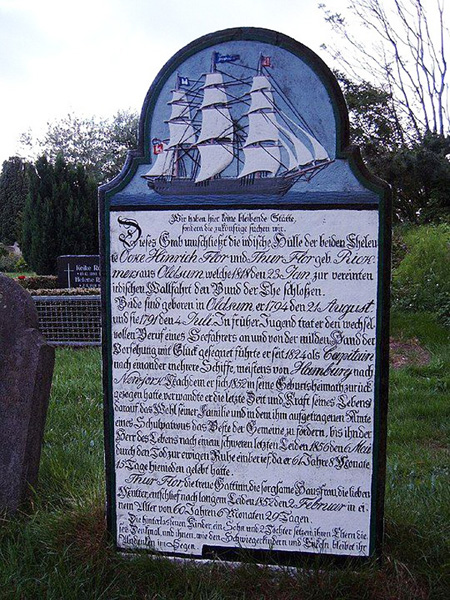

Damit eng verbunden sind Art, Umfang, Zugänglichkeit der Materialien, die als biografische Quellen genutzt werden können, zumal wenn kein Nachlass vorliegt.[129] Oder, wie es die Biografin Angela Steidele in ihrer „Poetik der Biographie“ auf den Punkt bringt: „‚Biographie‘ heißt ‚Leben schreiben‘. Zuallererst heißt es aber: Leben lesen, im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes: legere, sammeln, auflesen.“[130] Die textbasierte Überlieferung kann einerseits mit Oral History und partizipativen Methoden,[131] andererseits mit Fotografien, Ton, Film, Musik erweitert werden, wenn diese Quellen analytisch reflektiert in die Darstellung eingebracht und nicht nur als Illustration genutzt werden.[132] Gerade bei biografischen Studien ist es unerlässlich, die (autobiografischen) Quellen im Hinblick auf Selbst- und Fremdkonstruktionen zu untersuchen.[133] Anschließend ist die Form der Darstellung gut zu durchdenken, denn es gibt unterschiedliche biografische Formen.[134] Da Leben nicht linear war und ist, sollten Zeitlichkeit/en und Räumlichkeiten eingebunden und Kontingenz ernst genommen werden. Es kann auch nicht darum gehen, Lebensläufe nur als „Erfolgsgeschichten“ zu konzipieren, sondern Biograf:innen sollten ebenso nach (vermeintlichem) Scheitern fragen oder ganz andere Bewertungsschemata entwickeln.[135]

Im besten Fall ist eine biografische Studie in ihrer Struktur und Gestaltung so angelegt, dass der Konstruktionscharakter deutlich wird. Daher ist es wichtig, möglichst früh über die Anlage der biografischen Arbeit zu entscheiden, diese stetig zu überprüfen und dem Thema Grenzen zu setzen: Christian Klein strukturiert seine Lebensbeschreibung des Schriftstellers Ernst Penzoldt entlang der Metapher des Hauses, während Myriam Richter Werner von Melles Weg eng mit der Hamburger Stadt- und Universitätsgeschichte verknüpft. Sandra Richter entwirft den Menschen (weniger den Dichter) Rainer Maria Rilke aus einer „ironisch gebrochenen Distanz“, um „das Eigensinnige wie das Fragwürdige an Rilkes Werk zu erörtern“.[136]

Die Narration selbst, auch Sprache und Stil, sind besonders wichtig, um nicht Mythen zu reproduzieren oder Zuschreibungen zu reifizieren. Dabei kann ein:e Biograf:in (zumindest gedanklich) mit verschiedenen Darstellungsweisen, Stil- und Erzählformen experimentieren. Tilman Lahme nutzt für sein Buch über die Familie Mann das Präsens, um eine flüssigere, temporeiche Narration zu erreichen, um einen retrospektiven Blick zu vermeiden und stattdessen die Offenheit der historischen Situation zu betonen.[137] Statt einer teleologischen Arbeitsweise sollte die eigene Perspektive immer wieder geweitet werden, zum Beispiel indem das biografische Subjekt von den Rändern oder von „Gegenspieler:innen“ her gedacht wird, vergleichbare Lebensläufe herangezogen oder kontrafaktische Überlegungen angestellt werden (Was wäre, wenn …?).

Jörg Später situiert die Hauptfigur Siegfried Kracauer in dessen sozialem und intellektuellem Umfeld und konzipiert seine Studie als „soziale Biografie“, d.h., historische Kontexte werden zum Leben und Werk in Beziehung gesetzt, um Zusammenhänge zwischen unterschiedlichen Bereichen und Personen zu verdeutlichen.[138] Die Biografie ist daher auch eine Gruppenbiografie der Kollegen Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin und Ernst Bloch sowie ihrer gegenseitigen Sicht aufeinander, womit Kracauer zugleich dezentriert wird. Durch die Verbindung von Nahaufnahmen (auf das Individuelle, Besondere) mit der Totale (dem Repräsentativen, den Kontexten) wendet Später in seinem Narrativ außerdem Kracauers geschichtstheoretische Überlegungen an. Die Erwartung, dass eine Biografie vollständig zu sein habe, ist bei diesem Genre vielleicht noch größer als bei anderen historischen Erzählweisen. Wie jede historische Studie wird auch eine Biografie nie erschöpfend sein. Thematische oder zeitliche Schwerpunktsetzungen bzw. fehlende Überlieferung können stattdessen konstruktiv genutzt werden, zum Beispiel um zu erklären, was und warum weglassen wird (wie Privates, Kindheit, Alter).[139]

Mit diesen Schwierigkeiten müssen historische Studien generell einen Umgang finden – und wie alle historiografischen Ansätze hat auch die Biografik ihre Grenzen. Als Historiker:innen haben wir es immer (wieder) mit Lücken zu tun, zugleich birgt jede historische Fragestellung die Gefahr einer teleologischen Antwort. Biografie gilt vermutlich deshalb als besonders „gefährdet“, weil sie in der deutschsprachigen Geschichtswissenschaft teilweise von theoretischen und methodischen Debatten abgekoppelt war. Das hat sich geändert und vielleicht sogar ins Gegenteil gekehrt. Zumindest als Qualifikationsarbeit erfordert eine Biografie, frühzeitig über Arbeits- und Erzählweisen nachzudenken; ein Umstand, der im Vergleich zu anderen Ansätzen gegebenenfalls sogar vorteilhaft ist.

Autor:innen von Biografien sollten die Gestaltung der biografischen Darstellung reflektieren, damit die beschriebene Identität als konstruiert wahrgenommen werden kann. Hierbei geht es sowohl um die Subjektivierung, die jeder Lebensgeschichte zugrunde liegt, als auch um Erzählformen und narrative Strukturen, die eine Biografie als Biografie kennzeichnen. Die Diskussionen der letzten Dekaden verweisen darauf, dass Biografie als Biografie immer in sozialen, akademischen, literarischen Traditionen steht. Biograf:in und biografisches Subjekt, das publizierte Werk beweg(t)en sich in spezifischen diskursiven Feldern, die mit Prozessen der Legitimierung oder der Delegitimierung einhergehen, denn die Regeln des wissenschaftlichen Feldes, der zeitgenössischen Diskurse und des Buchmarkts ermöglichen oder verhindern Biografien oder auch experimentellere Formen der Darstellung.[140]

Pluralisierung bedeutet in diesem Kontext zum einen, über die Autor:innen von Biografien nachzudenken: Wer schreibt Biografien und warum? Wem gelingt es, die Texte zu veröffentlichen und wo? Zum anderen erklären diese Normen, warum sich beispielsweise die deutsche Biografieforschung mit bestimmten Fragen und Subjekten bisher kaum beschäftigt hat, sondern Biograf:innen vornehmlich über Persönlichkeiten der eigenen Region schrieben und schreiben. Diese nationalstaatliche Begrenzung lockert sich zurzeit, besonders im Rahmen der Global-, Migrations- und transnationalen Geschichte.

5. Fazit: Für mehr Biografien

Die Kritik an Biografien ebenso wie die theoretisch-methodische Pluralisierung des Fachs seit den 1980er-Jahren führten zu Veränderungen der Biografieforschung, indem „neue“ Subjekte und Themen vorgestellt werden. Diese Biografik geht nicht mehr von der Kohärenz eines Lebenslaufs, sondern von seiner Konstruktion aus, wenngleich Theorie und Praxis des Genres teilweise noch weit auseinanderklaffen. Die Leistungsfähigkeit und die Grenzen der Biografik müssen immer wieder neu ausgelotet, das Genre selbst reflektiert und mit geschichtstheoretischen Überlegungen verbunden werden. Denn eine Biografie zu schreiben, bedeutet auch, eine historische Fallstudie anzufertigen und sich damit im Spannungsfeld zwischen „allgemein-typisch“ oder „individuell-besonders“ zu bewegen.[141] Diese Zuspitzung ist meines Erachtens gar nicht notwendig und trifft für viele Lebens(-erzählungen) so auch nicht zu. Denn kann ein „Mensch als Ganzes“ überhaupt repräsentativ sein, sind es nicht nur bestimmte Lebensabschnitte oder Themen einer Biografie?

Fragen wie diese sollten in der Geschichtswissenschaft und in der Zeitgeschichtsschreibung diskutiert werden. Die Geschichte kann sich dabei von anderen Disziplinen inspirieren lassen, um die historische Biografik zu pluralisieren. Biografien, ebenso wie die theoretische und methodische Reflexion des Genres, können einen Beitrag dazu leisten, Geschichte zu dezentrieren, indem sie weniger vereindeutigen, sondern Fiktionalität und Kontingenz ernst nehmen und thematisieren. Biografie ist also gut geeignet, Geschichte – im positiven Sinn – zu verkomplizieren.

Ich plädiere für einen erweiterten Gattungsbegriff, der thematisch marginalisierte Subjekte, methodisch postkoloniale, queere und andere Ansätze einbezieht und neue Formen der Erzählung versucht. Das Erzählen wie auch die Materialgrundlage von Biografien verändern sich durch Digitalisierung und Medialisierung.[142] Diesen Wandel sollte die Geschichtswissenschaft aktiv mitgestalten und nutzen. Folglich ist es kein Zufall, dass (in der Geschichtswissenschaft) Biografien geschrieben werden. Da wir uns mit einer Lebensgeschichte „auf die Spuren von …“ begeben, bietet das Genre Entdeckungsfreude und zugleich die Möglichkeit der Wieder-Erinnerung, des Einschreibens von Akteur:innen in die Geschichte.[143]

Anmerkungen

[1] Kurt Tucholsky, All people on board!, in: Die Weltbühne, 29.11.1927, S. 870; online http://www.zeno.org/Literatur/M/Tucholsky,+Kurt/Werke/1927/All+people+on+board [30.07.2025].

[2] Jacques Le Goff, Wie schreibt man eine Biographie?, in: Fernand Braudel/Lucien Febvre/Arnaldo Momigliano/Natalie Zemon Davis/Carlo Ginzburg/Jacques LeGoff/Reinhart Koselleck, Der Historiker als Menschenfresser. Über den Beruf des Geschichtsschreibers, Berlin 1990, S. 103-112, hier S. 106.

[3] Margit Szöllösi-Janze, Biographie, in: Stefan Jordan (Hrsg.), Lexikon Geschichtswissenschaft: Hundert Grundbegriffe, Stuttgart 2002, S. 44-48, hier S. 44.

[4] Christian Klein, Analyse: Kontext, in: ders. (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie. Methoden, Traditionen, Theorien, Stuttgart ²2022, S. 303-307, hier S. 303.

[5] Cornelia Rauh-Kühne, Das Individuum und seine Geschichte. Konjunkturen der Biographik, in: Andreas Wirsching (Hrsg.), Neueste Zeit, München 2006, S. 215-232, hier S. 215.

[6] Peter Ackroyds „Biografie“ Londons ist eine populäre Kulturgeschichte: Peter Ackroyd, London. The Biography, London 2000; Stefan Wolles „Biografie“ Ost-Berlins (auch) DDR-Zeitgeschichte: Stefan Wolle, Ost-Berlin. Biografie einer Hauptstadt, Berlin 2020. Siehe beispielsweise auch: Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland/Marie-Louise von Plessen (Hrsg.), Der Rhein. Eine europäische Flussbiografie, München 2016; Jeannie Moser, Psychotropen. Eine LSD-Biographie, Konstanz 2013; Paul Nolte, Lebens Werk. Thomas Nipperdeys Deutsche Geschichte. Biographie eines Buches, München 2018; Rebecca Skloot, Die Unsterblichkeit der Henrietta Lacks, München 2010. Besonders in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte und im Museumsbereich handelt es sich bei Objektbiografien um ein produktives Forschungsfeld, da Arbeitsweisen, Institutionen und Akteur:innen der Wissenschaft bzw. Provenienzgeschichte und Bedeutungswandel thematisiert werden können: Samuel J.M.M. Alberti, Objects and the Museum, in: Isis 96 (2005), H. 4, S. 559-571; Lorraine Daston (Hrsg.), Biographies of Scientific Objects, Chicago/London 2000; Cornelia Geißler, Konzepte der Personalisierung und Individualisierung in der Geschichtsvermittlung. Die Hauptausstellung der KZ Gedenkstätte Neuengamme, in: Oliver von Wrochem (Hrsg.), Das KZ Neuengamme und seine Außenlager. Geschichte, Nachgeschichte, Erinnerung, Bildung, Berlin 2010, S. 315-328.

[7] Thomas Etzemüller, Biographien. Lesen – erforschen – erzählen, Frankfurt a.M. 2012; Bernhard Fetz (Hrsg.), Die Biographie – Zur Grundlegung ihrer Theorie, Berlin 2009; Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie; Hermione Lee, Biography. A very short Introduction, Oxford 2009; Birgitte Possing, Understanding Biographies. On Biographies in History and Stories in Biography, Odense 2017; Hans Renders/Binne de Haan (Hrsg.), Theoretical Discussions of Biography. Approaches from History, Microhistory, and Life Writing, Lewiston 2013. Elsbeth Bösl und Doris Gutsmiedl-Schümann haben eine lesenswerte Serie von Blogposts zur Biografieforschung publiziert; Ausgangspunkt der Beiträge ist: Elsbeth Bösl, Biografien und Biografierte, in: AktArcha, Hypotheses, 01.12.2024, https://aktarcha.hypotheses.org/8255 [30.07.2025].

[8] Christopher Meid, Biographik als Provokation. Wilhelm der Zweite (1925) von Emil Ludwig, in: Christian Klein/Falko Schnicke (Hrsg.), Legitimationsmechanismen des Biographischen. Kontexte – Akteure – Techniken – Grenzen, Bern 2016, S. 223-244, hier S. 224f. Zur zeitgenössischen Debatte siehe auch: Siegfried Kracauer, Die Biographie als neubürgerliche Kunstform [1930], in: Das Ornament der Masse, Frankfurt a.M. 1970, S. 75-80; Leo Löwenthal, Die biographische Mode, in: Theodor W. Adorno/Walter Dirks (Hrsg.), Sociologica. Aufsätze. Max Horkheimer zum sechzigsten Geburtstag gewidmet, Bd. 1, Frankfurt a.M. 1955, S. 363-386.

[9] Einen guten Überblick geben: Angelika Schaser, Emil Ludwigs Fingerzeig auf die Biographien in der Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Unseld/von Zimmermann (Hrsg.), Anekdote – Biographie – Kanon, S. 176-193, hier S. 180ff.; Stephan Porombka, Populäre Biographik, in: Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 181-191.

[10] Fast alle in den Fußnoten genannten Einführungs- und Übersichtswerke beginnen mit einem historischen Abriss zur Entwicklung des Genres Biografie. Hier sei verwiesen auf Bernhard Fetz, Die vielen Leben der Biographie. Interdisziplinäre Aspekte einer Theorie der Biographie, in: ders. (Hrsg.), Die Biographie, S. 3-66, hier S. 11ff., die entsprechenden Abschnitte in Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 329ff., und in Anne-Marie Monluçon/Agathe Salha (Hrsg.), Fictions biographiques XIXe - XXIe siècles, Toulouse 2007, S. 33ff.

[11] Stanley Fish, Just Published: Minutiae without Meaning, in: New York Times, 07.09.1999.

[12] Zum Biografen Johnson und seinem Biografen Boswell finden sich Übersichten mit weiteren Literaturhinweisen bei Barbara Caine, Biography and History, London 2019 [2010]; Nigel Hamilton, Biography. A Brief History, Cambridge 2007; Michael Jonas, Britische Biographik, in: Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 423-432; Caitriona Ní Dhúill, Den Stil bestimmen. Samuel Johnsons Ratschläge für Biographen, in: Bernhard Fetz/Wilhelm Hemecker (Hrsg.), Theorie der Biographie. Grundlagentexte und Kommentar, Berlin 2011, S. 13-17. Siehe auch die Kollektivbiografie von Leo Damrosch, The Club. Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends who Shaped an Age, New Haven 2019. Zum Historiker Droysen siehe Falko Schnicke, Prinzipien der Entindividualisierung. Theorie und Praxis biographischer Studien bei Johann Gustav Droysen, Köln 2010, sowie ders., Elemente biographischer Legitimation, Funktionen historischer Forschung: Johann Gustav Droysens „Friedrich I. König von Preußen“ (1867, GPP IV/1), in: Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 96 (2014), H. 1, S. 27-56.

[13] Zur Geschichte der Biografie siehe u.a.: Caine, Biography and History; François Dosse, Le pari biographique, Paris 2005; Caitríona Ní Dhúill, Metabiography: Reflecting on Biography, New York 2020; Olaf Hähner, Historische Biographik. Die Entwicklung einer geschichtswissenschaftlichen Darstellungsform von der Antike bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, Frankfurt a.M. 1999; Hamilton, Biography; Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie; Lee, Biography; Helmut Scheuer, Biografie, in: Helmut Reinalter/Peter J. Brenner (Hrsg.), Lexikon der Geisteswissenschaften. Sachbegriffe – Disziplinen – Personen, Wien 2011, S. 80-85; William Roscoe Thayer, The Art of Biography, Folcroft 1977 [1920].

[14] Zu den Entwicklungen in den USA siehe Levke Harders, US-amerikanische Biographik, in: Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 463-474. Dort finden sich eine ausführlichere Darstellung und weiterführende Literaturhinweise. Zu Großbritannien siehe Jonas, Britische Biographik.

[15] Marietta A. Hyde, Modern Biography, New York 1931; Howard M. Jones, Methods in Contemporary Biography, in: English Journal 21 (1932), H. 2, S. 113-122; Thayer, The Art of Biography.

[16] Christian Klein/Falko Schnicke, Biographik im 20. Jahrhundert, in Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 365-381, hier S. 372f. Siehe auch Fetz, Die vielen Leben, S. 26ff.; Andreas Gestrich/Peter Knoch/Helga Merkel (Hrsg.), Biographie – sozialgeschichtlich. Sieben Beiträge, Göttingen 1988; Hagen Schulze, Die Biographie in der „Krise der Geschichtswissenschaft“, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 29 (1978), S. 508-518.

[17] Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte. Bd. 1: Vom Feudalismus des Alten Reiches bis zur defensiven Modernisierung der Reformära, 1700-1815, München 1987, S. 30.

[18] Andreas Gestrich, Einleitung: Sozialhistorische Biographieforschung, in: Gestrich/Knoch/Merkel (Hrsg.), Biographie – sozialgeschichtlich, S. 5-28, hier S. 20.

[19] Siehe u.a. Anthony M. Friedson (Hrsg.), New Directions in Biography, Honolulu 1981; Stephen B. Oates (Hrsg.), Biography as high Adventure. Life-Writers Speak on their Art, Amherst 1986.

[20] Leon Edel, Writing Lives. Principia Biographica, New York 1984. Kritik u.a. von Ira B. Nadel, Biography. Fiction, Fact and Form, London, Basingstoke 1985.

[21] Judith Butler, Das Unbehagen der Geschlechter, Frankfurt a.M. 1991, S. 38.

[22] Pierre Bourdieu, Die biographische Illusion, in: BIOS 3 (1990), H. 1, S. 75-81, online https://doi.org/10.3224/bios.v32i1-2.05 [30.07.2025].

[23] Simone Lässig, Die historische Biographie auf neuen Wegen?, in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 60 (2009), H. 10, S. 540-553, hier S. 546. Siehe beispielsweise auch: Peter Alheit/Bettina Dausien, „Biographie“ in den Sozialwissenschaften. Anmerkungen zu historischen und aktuellen Problemen einer Forschungsperspektive, in: Fetz (Hrsg.), Die Biographie, S. 285-315.

[24] Lässig, Die historische Biographie, S. 546.

[25] Eine Auswahl theoretischer und methodischer Texte zur Biografie als Gattung findet sich in: Fetz/Hemecker (Hrsg.), Theorie der Biographie, und als leicht veränderte englische Ausgabe: Wilhelm Hemecker/Edward Saunders (Hrsg.), Biography in Theory. Key Texts with Commentaries, Berlin 2017. Die theoretisch- methodischen Debatten in der europäischen, vor allem deutschsprachigen, Geschichtswissenschaft im 19. Jahrhundert diskutiert Sabina Loriga, Le petit x. De la biographie à l’histoire, Paris 2010.

[26] Um die rassistischen Konstruktionen und die damit verbundenen Ungleichheitsverhältnisse als solche (zu versuchen) sichtbar zu machen, schreibe ich weiß klein und kursiv. Siehe u.a. Emily Ngubia Kuria, eingeschrieben. Zeichen setzen gegen Rassismus an deutschen Hochschulen, Berlin 2015, S. 22.

[27] Desley Deacon/Penny Russell/Angela Woollacott (Hrsg.), Transnational Lives. Biographies of Global Modernity, 1700-Present, New York 2010; Mary Rhiel/David Suchoff (Hrsg.), The Seductions of Biography, New York 1996. Mit einem Fokus auf Autobiografien: Bart Moore-Gilbert, Postcolonial Life-Writing. Culture, Politics and Self-Representation, London 2009.

[28] Shirley A. Leckie, Biography Matters: Why Historians Need well-crafted Biographies more than ever, in: Lloyd E. Ambrosius (Hrsg.), Writing Biography: Historians & Their Craft, Lincoln 2004, S. 1-26, hier S. 14ff. Siehe dazu auch: Volker Depkat, Biographieforschung im Kontext transnationaler und globaler Geschichtsschreibung, in: BIOS 28 (2015), H. 1-2, S. 3-18, online https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/bios/article/view/26982 [30.07.2025]; Klaas van Walraven (Hrsg.), The Individual in African History: The Importance of Biography in African Historical Studies, Leiden 2020.

[29] Natalie Zemon Davis, Leo Africanus. Ein Reisender zwischen Orient und Okzident, Berlin 2008; dies., Dezentrierende Geschichtsschreibung. Lokale Geschichten und kulturelle Übergänge in einer globalen Welt, in: Historische Anthropologie 19 (2011), H. 1, S. 144-156.

[30] Lässig, Die historische Biographie, S. 542. Lässig verweist hier auf Carlo Ginzburg, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Giovanni Levi und Natalie Zemon Davis – und damit auf Forschungen zur Frühen Neuzeit, die alltags-, mikro- und geschlechterhistorische Fragestellungen früher als die Zeitgeschichte integriert haben.

[31] Schaser, Emil Ludwig, S. 189. Parallel existiert eine positivistische Sicht auf Biografien, beispielsweise bei Robert I. Rotberg, Biography and Historiography: Mutual Evidentiary and Interdisciplinary Considerations, in: Journal of Interdisciplinary History 40 (2010), H. 3, S. 305-324.

[32] Schaser, Emil Ludwig, S. 192.

[33] Ebd., S. 193. Ein aussagekräftiges Beispiel dafür ist z.B. Hans-Christof Kraus, Geschichte als Lebensgeschichte. Gegenwart und Zukunft der politischen Biographie, in: ders./Thomas Nicklas (Hrsg.), Geschichte der Politik. Alte und Neue Wege, München 2007, S. 311-332.

[34] In den USA gingen knapp zehn Millionen Bücher im Bereich Biografie, Autobiografie und Memoiren allein im ersten Halbjahr 2018 über den Ladentisch, womit das Genre an sechster Stelle in der Sparte Sachbuch stand (mit 21,2 Millionen nahmen Bibeln und Sachbücher zum Thema Religion den ersten Platz ein), so Publishers Weekly, Unit sales of adult nonfiction books in the United States in the first half of 2018, by category, in: Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/426841/ebook-market-distribution-by-genre-usa/ [30.07.2025]. Neuere Zahlen für die einzelnen Genres in den USA liegen nicht vor; auch die statistischen Übersichten zum deutschen Buchmarkt schlüsseln Biografien nicht als eigene Sparte auf, sondern diese finden sich u.a. im Bereich Sachbuch (mit insg. 10,6 Prozent des Umsatzes im Buchhandel), Geisteswissenschaften (4,4 Prozent) und anderen Bereichen; Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels, Umsatzanteile der einzelnen Warengruppen im Buchhandel in Deutschland in den Jahren 2018 und 2019, in: Statista, https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/71155/umfrage/umsatzanteile-im-buchhandel-im-jahr-2008-nach-genre/ [30.07.2025]. Allgemein zum Thema siehe Stephan Porombka, Biographie und Buchmarkt, in: Klein (Hrsg.), Handbuch Biographie, S. 643-650.

[35] Dies ließ sich lange Zeit deutlich an den renommierten Pulitzer-Preisen für Biografie und Autobiografie erkennen: The Pulitzer Prizes, https://www.pulitzer.org/prize-winners-by-category/222 [30.07.2025]. Siehe dazu auch den Abschnitt „Les grands hommes: fonctions sociales et politiques du biographique“ in der Anthologie von Sarah Mombert/Michèle Rosellini (Hrsg.), Usages des vies. Le biographique hier et aujourd'hui (XVIIe-XXIe siècle), Toulouse 2012.

[36] Possing, Understanding Biographies, S. 49-68. Dabei gibt es erhebliche nationale Unterschiede. Possing wertet in ihrer Studie weibliche und männliche, keine nicht-binären Forschenden und biografischen Subjekte aus.

[37] Vincent Broqua/Guillaume Marche, L’épuisement du biographique?, in: dies. (Hrsg.), L’épuisement du biographique?, Newcastle upon Tyne 2010, S. 1-21.

[38] Siehe u.a. Johanna Gehmacher, Leben schreiben. Stichworte zur biografischen Thematisierung als historiografisches Format, in: Lucile Dreidemy/Richard Hufschmied/Agnes Meisinger/Berthold Molden/Eugen Pfister/Katharina Prager/Elisabeth Röhrlich/Florian Wenninger/Maria Wirth (Hrsg.), Bananen, Cola, Zeitgeschichte. Oliver Rathkolb und das lange 20. Jahrhundert, Bd. 2, Wien u.a. 2015, S. 1013-1026, hier S. 1014; Schaser, Emil Ludwig, S. 178.

[39] Siehe Center for Biographical Research, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/cbr/, und die dort herausgegebene Zeitschrift „Biography“, http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/bio [beide 30.07.2025].

[40] Siehe die Zeitschriften „Auto/Biography Studies“, https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raut20, und „Life Writing“, https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rlwr20 [beide 30.07.2025].

[41] Siehe The Leon Levy Center for Biography, CUNY, https://llcb.ws.gc.cuny.edu [30.07.2025].

[42] Siehe Institut für Geschichte und Biographie, Fernuniversität Hagen, https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/geschichteundbiographie, und die dort herausgegebene Zeitschrift „BIOS“, https://www.fernuni-hagen.de/geschichteundbiographie/bios/index.shtml [beide 30.07.2025].

[43] Siehe Zentrum für Biographik, https://zentrum-fuer-biographik.de, Forschungsverbund Geschichte und Theorie der Biographie, Universität Wien https://gtb.univie.ac.at, und Biografie Instituut, Universität Groningen, https://www.rug.nl/research/biografie-instituut/?lang=en [alle 30.07.2025].

[44] Siehe International Autobiography Association, https://sites.google.com/ualberta.ca/iaba/home [30.07.2025].

[45] Siehe Global Biography Working Group, https://www.global.bio/ [30.07.2025]. Die Arbeitsgruppe hat einen Sammelband mit biografischen Fallbeispielen herausgegeben: Laura Almagor/Haakon A. Ikonomou/Gunvor Simonsen (Hrsg.), Global Biographies. Lived History as Method, Manchester 2022.

[46] Siehe dazu beispielsweise Volker Depkat, The Challenges of Biography. European-American Reflections, in: Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 55 (2014), S. 39-48, online https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/ploneimport3_derivate_00002625/depkat_challenges.pdf; ders., Biographieforschung im Kontext transnationaler und globaler Geschichtsschreibung, in: BIOS 28 (2015), H. 1-2, S. 3-18, online https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/bios/article/view/26982 [beide 30.07.2025]; Claudia Ulbrich/Hans Medick/Angelika Schaser (Hrsg.), Selbstzeugnis und Person. Transkulturelle Perspektiven, Köln 2012. Aus literaturwissenschaftlicher Perspektive über US-Autor:innen: Marija Krsteva, Towards a Theory of Life-Writing. Genre Blending, Abingdon 2022.

[47] Vgl. Lässig, Die historische Biographie, S. 542.

[48] Ich beziehe mich im Folgenden vor allem auf Fetz, Die vielen Leben; Lässig, Die historische Biographie. Siehe auch: Christopher Beckmann, Nach der „Individualitätsprüderie“: Die ungebrochene „Faszination des Biographischen“. Zeitgeschichtliche biographische Neuerscheinungen 2012, in: Historische Mitteilungen 26 (2013/2014), S. 419-443; Ulrich Herbert, Über Nutzen und Nachteil von Biographien in der Geschichtswissenschaft, in: Beate Böckem/Olaf Peters/Barbara Schellewald (Hrsg.), Die Biographie – Mode oder Universalie? Zu Geschichte und Konzept einer Gattung in der Kunstgeschichte, Berlin 2015, S. 3-16.

[49] Volker Ullrich, Die schwierige Königsdisziplin. Das biografische Genre hat immer noch Konjunktur. Doch was macht eine gute historische Biografie aus?, in: Die Zeit 15, 04.04.2007, online https://www.zeit.de/2007/15/P-Biografie [30.07.2025].

[50] Ebd.

[51] Michel Biard/Hervé Leuwers (Hrsg.), Danton. Le mythe et l’histoire, Paris 2016; Bernd Florath (Hrsg.), Annäherungen an Robert Havemann. Biographische Studien und Dokumente, Göttingen 2016; Barbara von Hindenburg, Die Abgeordneten des Preußischen Landtags 1919-1933. Biographie – Herkunft – Geschlecht, Frankfurt a.M./Bern 2017; Carolyn Steedman, An Everyday Life of the English Working Class. Work, Self and Sociability in the Early Nineteenth Century, Cambridge 2013.

[52] Michael A. Chaney (Hrsg.), Graphic Subjects. Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels, Madison 2011; Richard Iadonisi (Hrsg.), Graphic History. Essays on Graphic Novels and/as History, Newcastle 2024. In jüngster Zeit gibt es einige grafische Biografien über die Shoa, so zum Beispiel: Hannah Brinkmann, Zeit heilt keine Wunden. Das Leben des Ernst Grube, Berlin 2024; Ginette Kolinka/Victor Matet, Adieu Birkenau – Eine Überlebende erzählt, Bielefeld 2024; Barbara Yelin, Emmie Arbel. Die Farbe der Erinnerung, Berlin 2023.

[53] Siehe u.a. Jan Bachmann, Mühsam. Anarchist in Anführungsstrichen, Zürich 2018; Ángel de la Calle, Modotti. Eine Frau des 20. Jahrhunderts, Berlin 2011; Béatrice Gysin/Bettina Wohlfender/Mirjam Janett, Berta, Biel 2023; Reinhard Kleist, Der Boxer. Die wahre Geschichte des Hertzko Haft, Hamburg 2012; Ken Krimstein, Die drei Leben der Hannah Arendt, München 2019; Birgit Weyhe, Rude Girl, Berlin 2022.

[54] Siehe u.a. Thomas S. Freeman/David L. Smith (Hrsg.), Biography and History in Film, Cham 2019.

[55] Als Beispiele für virtuelle Biografien: Martin Otto Braun/Elisabeth Schläwe/Florian Schönfuß (Hrsg.), Netzbiographie – Joseph zu Salm-Reifferscheidt-Dyck (1773-1861), Köln 2014 [30.07.2025], online https://dx.doi.org/10.18716/map/00005; Katharina Prager, Karl Kraus Online, 2017, http://www.kraus.wienbibliothek.at [beide 30.07.2025]; Hannes Schweiger, Ernst Jandl vernetzt. Multimediale Wege durch ein Schreibleben (DVD), Wien 2011, und für eine gelungene biografische Ausstellung: Aris Fioretos, Flucht und Verwandlung. Nelly Sachs, Schriftstellerin, Berlin 2010. Gleichzeitig werden auto/biografische Accounts historischer Akteur:innen auf Kurznachrichtendiensten publiziert oder historische Leben auf Instagram dargestellt. Zu Letzterem siehe u.a. Mia Berg/Christian Kuchler (Hrsg.), @ichbinsophiescholl. Darstellung und Diskussion von Geschichte in Social Media, Göttingen 2023.

[56] Die Frage, was eine Biografie (nicht) leisten könne, stellten schon Johann Gustav Droysen, Historik, Stuttgart 1977 [1857], S. 242-244, und Wilhelm Dilthey, Die Biographie [1910], in: Der Aufbau der geschichtlichen Welt in den Geisteswissenschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 1981, S. 303-310.

[57] Bisher wurde die DDR-Geschichte vor allem kollektivbiografisch erforscht, siehe u.a. Christiane Lahusen, Zukunft am Ende. Autobiographische Sinnstiftungen von DDR-Geisteswissenschaftlern nach 1989, Bielefeld 2014; Lutz Niethammer/Alexander von Plato/Dorothee Wierling, Die volkseigene Erfahrung. Eine Archäologie des Lebens in der Industrieprovinz der DDR. 30 biographische Eröffnungen, Berlin 1991; Dorothee Wierling, Geboren im Jahr Eins. Der Jahrgang 1949 in der DDR. Versuch einer Kollektivbiographie, Berlin 2002. Für Einzelbiografien siehe u.a. Jörg Magenau, Christa Wolf. Eine Biographie, Berlin 2002; Martin Sabrow, Erich Honecker. Das Leben davor. 1912-1945, München 2016. Für eine sozialwissenschaftliche Perspektive siehe Ingrid Miethe, Biographieforschung über Ostdeutschland – eine Forschung wie jede andere?, in: Laura Behrmann/Markus Gamper/Hanna Haag (Hrsg.), Vergessene Ungleichheiten. Biographische Erzählungen ostdeutscher Professor*innen, Bielefeld 2024, S. 101-126.

[58] Martin Sabrow, Der führende Repräsentant. Erich Honecker in generationsbiographischer Perspektive, in: Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History 10 (2013), H. 1, online https://zeithistorische-forschungen.de/1-2013/4665 [30.07.2025], S. 61-88.

[59] Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk, Walter Ulbricht. Der deutsche Kommunist (1893-1945), München 2023; ders., Walter Ulbricht. Der kommunistische Diktator (1945-1973), München 2024.

[60] Zur politikhistorischen Biografik siehe: Dosse, Le pari biographique, S. 346-354; Alexander Gallus, Biographik und Zeitgeschichte, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 01-02/2005, S. 40-46, online http://www.bpb.de/publikationen/249NFW,0,0,Biographik_und_Zeitgeschichte.html [30.07.2025]; Ann-Christina L. Knudsen/Karen Gram-Skjoldager (Hrsg.), Living Political Biography. Narrating 20th Century European Lives, Aarhus 2012; Kraus, Geschichte als Lebensgeschichte; Guillaume Piketty, La biographie comme genre historique? Étude de cas, in: Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire 63 (1999), H. 3, S. 119-126.

[61] Gerade für diesen Abschnitt über Politikgeschichte gilt, dass ich nur einige wenige Beispiele aus der Vielzahl der vorliegenden Studien nenne: Marleen von Bargen, Anna Siemsen (1882-1951) und die Zukunft Europas. Politische Konzepte zwischen Kaiserreich und Bundesrepublik, Stuttgart 2017; Anastasia C. Curwood, Shirley Chisholm. Champion of Black Feminist Power Politics, Chapel Hill 2023; Lothar Gall, Walther Rathenau. Portrait einer Epoche, München 2009; Julian Jackson, A Certain Idea of France. The Life of Charles de Gaulle, London 2018; Hans-Peter Schwarz, Adenauer. Bd. 1: Der Aufstieg 1876-1952, Bd. 2: Der Staatsmann 1952-1967, Stuttgart 1986 und 1991; Jonathan Sperber, Karl Marx. Sein Leben und sein Jahrhundert, München 2013; Maria Wirth, Hertha Firnberg und die Wissenschaftspolitik. Eine biografische Annäherung, Göttingen 2023.

[62] Ulrich Herbert, Best. Biographische Studien über Radikalismus, Weltanschauung und Vernunft, 1903-1989, Bonn 1996; Peter Longerich, Heinrich Himmler. Biographie, München 2008; Wolfram Pyta, Hindenburg. Herrschaft zwischen Hohenzollern und Hitler, München 2007.

[63] Lucy Riall, Garibaldi. Invention of a Hero, New Haven 2007; Axel Schildt, Inszenierung einer Biographie – Konstruktion einer Karriere. Der Rechtsintellektuelle Armin Mohler (1920-2003), in: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 70 (2019), H. 9-10, S. 554-567; Daniel Siemens, Horst Wessel. Tod und Verklärung eines Nationalsozialisten, München 2009. Siehe auch: Lucy Riall, The Shallow End of History? The Substance and Future of Political Biography, in: Journal of Interdisciplinary History 40 (2010), H. 3, S. 375-397; Volker Ullrich, Der Mythos Bismarck und die Deutschen, in: Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 13/2015, S. 15-22, online https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/202983/der-mythos-bismarck-und-die-deutschen/?p=all [30.07.2025].

[64] Karl Heinrich Pohl, Gustav Stresemann. Biografie eines Grenzgängers, Göttingen 2015, S. 9; Philipp Kufferath, Peter von Oertzen (1924-2008). Eine politische und intellektuelle Biografie, Göttingen 2017.

[65] Pohl, Gustav Stresemann, S. 8f.

[66] Zum Beispiel: Sandra Dahlke/Nikolaus Katzer/Denis Sdvizhkov (Hrsg.), Revolutionary Biographies in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Imperial – Inter/national – Decolonial, Göttingen 2024, online https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/pdf/10.14220/9783737012485; Johanna Gehmacher, Feminist Activism, Travel and Translation around 1900. Transnational Practices of Mediation and the Case of Käthe Schirmacher, Cham 2024, online https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/86483/PUB_1031_Gemacher_Feminist_Activism.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y; Francisca de Haan (Hrsg.), The Palgrave Handbook of Communist Women. Activists around the World, Cham 2023; Shuyang Song, Intersektionale Perspektiven auf das politische Selbstverständnis der Westdeutschen Frauenfriedensbewegung (1951-1974), in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften 35 (2024) H. 3, S. 142-163, online https://journals.univie.ac.at/index.php/oezg/article/view/9187/9296 [alle 30.07.2025]; Brigitte Studer, Reisende der Weltrevolution. Eine Globalgeschichte der Kommunistischen Internationale, Berlin 2020; Heidrun Zettelbauer, Gratwanderungen entlang des Un/Politischen. Intersektionale Annäherungen an Akteurinnen des deutschnational-völkischen Milieus (1880-1918), in: Barbara Haider-Wilson/Waltraud Schütz (Hrsg.), Frauen als politisch Handelnde. Beiträge zur Agency in der Habsburgermonarchie, 1780-1918, Bielefeld 2025, S. 167-194, online https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/102615/ssoar-2025-haider-wilson_et_al-Frauen_als_politisch_Handelnde_Beitrage.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y&lnkname=ssoar-2025-haider-wilson_et_al-Frauen_als_politisch_Handelnde_Beitrage.pdf [alle 30.07.2025].

[67] Hannes Schweiger, Polyglotte Lebensläufe. Die Transnationalisierung der Biographik, in: Michaela Bürger-Koftis/Hannes Schweiger/Sandra Vlasta (Hrsg.), Polyphonie – Mehrsprachigkeit und literarische Kreativität, Wien 2010, S. 23-38, hier S. 25. Zur Übersicht: Levke Harders, Migration und Biographie. Mobile Leben beschreiben, in: Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften 29 (2018), H. 3, S. 17-36, online https://journals.univie.ac.at/index.php/oezg/article/view/3358/3649 [30.07.2025].

[68] Dieser Befund trifft auf fast alle (der hier genannten) politikhistorischen Biografien zu. Am Beispiel neuerer Biografien über Otto von Bismarck diskutiert diesen Aspekt Katharina Prager, „Die Lektüre von historischen Biographien ist gefährlich“ – Aktuelle Bismarck-Biografik, in: Neue Politische Literatur 61 (2016), H. 3, S. 377-387.

[69] Siehe z.B. Hans Belting/Andrea Buddensieg, Ein Afrikaner in Paris. Léopold Sédar Senghor und die Zukunft der Moderne, München 2018; Helwig Schmidt- Glintzer, Mao Zedong. „Es wird Kampf geben“, Berlin 2017; Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi. The Years That Changed the World, 1914-1948, London 2018. Für das frühe 19. Jahrhundert: Sudhir Hazareesingh, Black Spartacus. Das große Leben des Toussaint Louverture, München 2022.