African American history now occupies an important place in American historiography. As a branch of historical scholarship, it concerns the lives and experiences of people of African origin from the colonial period to the present day. Enslaved, segregated and reduced to the status of second-class citizens, African Americans have engaged in a long struggle, first for their freedom, then for integration and equal rights. Ever since the arrival of the first Africans to America in the seventeenth century, massive social inequality existed between the Black minority and the white majority society that understood Blacks as inferior and attempted to oppress and exploit them to their own advantage. Their inferior status is also reflected in their marginalization in American historiography.

Many African Americans have been keenly aware of the power of history, its significance for the American nation and America’s self-image, for the social position and integration of individuals as well as for their own race. As early as the eighteenth century, but especially since the nineteenth century, Blacks advocated for appropriate representation in American historiography – long to no avail. At the same time, however, they began to tell their own story, providing a written record of their collective fate and the important role they have played in the project of the American nation. African American historiography has also been an attempt at self-discovery and self-positioning in a nation where Blacks have been living almost from the start without the majority of them being fully accepted members of society and where they have often been overlooked in the country’s historical narratives.[1]

In this respect, African American historical scholarship is part of the struggle for freedom and equality, for the end of racism, as well as for political and social influence. Its orientation and focus are therefore strongly informed by the social and political trends of the day. Referred to as “Negro history” into the 1960s, with the social reform and protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s the term was successively replaced by other labels: Black history, Afro-American history and, its current designation, African American History.[2] Debates about Black identity are ongoing, as well as how to call and even spell related concepts. In 2020, leading newspapers in the United States made a conscious decision to capitalize “Black” while retaining the lowercase spelling of “white” so as not to abet notions of white supremacy.[3] Writing the term with a capital letter is meant to denote a culture and shared set of experiences rather than an identifying skin color. There have also been numerous discussions about whether the term African American is too vague.[4]

This essay is divided into five chapters. It begins by addressing “race” in order to show that the notion is a construct. It will then discuss the position of Africans and African Americans in American historical narratives and the genesis of African American historiography. In doing so it points to the close link between historiography, the fight for freedom and the civil rights movement in the nineteenth and especially the twentieth century. This is followed by an account of current research approaches and focal points in African American historical scholarship. The essay concludes with a look at the future of African American history.

1. Race

There is general agreement among historians that race[5] is a social construct that needs to be critically assessed and historicized as an organizing category. But even if race is understood as a construct, no analysis of the development of American society in general and the African American experience in particular can get by without making frequent reference to it. Race and questions of racial identity, especially as a means of empowerment, still play a central role in African American history and historiography.

Race is a relational construct built on a contrived difference and dichotomy (e.g., white vs. Black). Skin color, in this context, became the main characteristic for identifying and understanding physical, mental, and cultural differences especially in Western discourses. “Blackness” and “whiteness”[6] are constructs too, being constantly redefined, filled with meaning and hierarchized. An analysis of how “Black” and “white” are constructed in the United States offers insight into how the concept of race has functioned, been functionalized, and shaped the social order.[7]

In short, race has been used by the white majority to order American society, to establish and perpetuate hierarchies between various phenotypes and “skin colors,” and to justify the enslavement, exclusion, or segregation of sections of the population. Ibram X. Kendi, however, in his widely received work Stamped from the Beginning, inverts the order of the emergence of race and racism, arguing that racist ideas have been developed in order to justify repressive choices and actions in all walks of life. In the case of the United States, this inversion of causality would mean that whites invented the notion of Black inferiority mainly out of economic self-interest. Accordingly, racism served to legitimize the ruthless enslavement and exploitation of Blacks.[8]

Whereas it was initially mostly Black, for its part, is very critical of the concept of “Rasse” (race). Its use entails the risk of “normalizing this category in the German-speaking world,” a category that inevitably “still refers to Auschwitz.”[9] It is this link to Nazism that makes any use of the term unacceptable in the view of many scholars in this part of the world. When they do use it, then often the English term or the German “Rasse” in scare quotes in order to distance the term from Nazism[10] and to make a distinction between the American concept of race and the German concept of “Rasse”. And yet the question[11] arises if there really is any clear distinction between the two concepts in terms of their legitimacy, interpretation or use in the American and German contexts. The quotation marks, at any rate, underscore the constructed nature of the category, since the idea of race as a sociocultural concept is still more firmly entrenched in the English-speaking world than the corresponding term in the German.[12]

2. Between Slavery and Segregation

Blacks came to the New World in a variety of ways with the onset of colonial settlement in the seventeenth century. The majority of them, however, were brought against their will as enslaved people. Neither the Declaration of Independence in 1776 nor the American Constitution of 1787, proclaiming in the spirit of the Enlightenment the inalienable rights and the equality of all human beings, did anything to change this.[13] Even in areas where slavery was not very prevalent,[14] whites tended to view Blacks as inferior or as children in need of a “strong white hand.” For centuries, white people used the Bible, and later race-based science such as Social Darwinism or eugenics, to justify the oppression and exploitation of Blacks.[15]

Even after the legal abolition of slavery with the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Blacks remained socially and economically dependent and still subject to control in much the same way as they had been before. Most importantly, the constitutional amendment still allowed for enslavement and forced labor in the case of individuals convicted of a crime. The white majority society used this restriction, particularly in the American South, to establish a system of mass forced labor in state and private institutions, targeting Black individuals who increasingly became the victims of an arbitrary system of criminal justice and ended up behind bars.[16] Blacks were even stripped of their newly won civil rights under the Fourteenth Amendment and their right to vote under the Fifteenth Amendment ratified in 1870. Reading tests, poll taxes and other such regulations effectively curtailed their right to vote.

Segregation increasingly governed the relations between Blacks and whites. Interracial relationships and marriage were prohibited in many states into the 1960s. Plessy v. Ferguson, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision of 1896 legitimizing the provision of separate facilities for Blacks and whites – in this case allowing separate train cars – established the doctrine of “separate but equal” in the South.[17] The result was neither equal treatment nor equal facilities for Blacks. Buses and streetcars had separate cars for whites and Blacks, or Blacks had to sit at the back of the bus. In other areas of public life as well, the established system of segregation meant systematic discrimination against Blacks. Signs were put up to designate separate toilets and entrances. Separate schools with poorer facilities and funding were established for Blacks in order to perpetuate segregation. Blacks, simply by virtue of being Black, were reduced to second-class citizens, not to mention being constantly subject to the despotism of whites. Violence and threats of violence against African Americans, which culminated in the practice of lynching, were omnipresent in the late nineteenth and well into the twentieth century.[18]

![Photographer: Jack Delano, At the Bus Station in Durham, North Carolina, May 1940. U.S. Farm Security Administration / Office of War Information Black & White Photographs]. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington / Wikimedia Commons (public domain)](/sites/default/files/inline-images/800px-JimCrowInDurhamNC_0.jpg)

This situation did not go unchallenged. Since the days of slavery Blacks had fought back directly or indirectly, first for their freedom, later for their equality and a life in peace and prosperity. They tried to expand their scope of action and assert their civil rights, fought against lynching, and demanded the end of segregation in all areas of society.[19] Faced with continued exclusion and oppression, they built up a “parallel society”[20] with their own newspapers, schools, universities, businesses and churches. Discovering and recording their own history was also part of this.

3. The Emergence of African American History

Given their roots in Africa, a continent with predominantly oral traditions in a multitude of languages, people of African origin in America likewise tended to preserve their history and culture through oral means.[21] Most Africans in the American diaspora were in fact illiterate, as it was forbidden to teach enslaved people how to read and write, educated Blacks being considered a threat to the existing system of oppression and exploitation.[22] Thus, African American historiography in its early phases was primarily based on an oral tradition.[23]

Filled with the notion of its own superiority, the white majority society long deliberately ignored Blacks in their national historiography and memory culture, as well as more generally in public discourse, or they depicted them in a stereotypical manner. Black men were either portrayed as submissive slaves or lascivious beasts who were incapable of living and functioning in a modern society without the supervision of white men. Black women, too, were reduced to subordinate roles through stereotypical representations, e.g., as an asexual mammy or hypersexual Jezebel.[24] Their contributions to the development of the Unites States found no place in history books nor in the general public discourse.

The exclusion or distortion of African Americans in historical narrative and collective memory was another powerful strategy of oppression and discrimination against Blacks in American society.[25] In their struggle against slavery and subsequent segregation, African Americans therefore endeavored early on to make clear to the white population as well as to themselves the important role they have played in the history of the American nation as well as in American culture. In the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century, runaway slaves such as Boston King, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Ann Jacobs tried to make their voices heard and leave a written record of their experiences.[26] Their memoirs were an attempt to let Blacks go down in American history as actors in their own right, demanding recognition for their contribution to the American nation.

In his 1986 article on the development of African American historiography, still widely cited today, historian John Hope Franklin divides the latter into four generations. Accordingly, over the decades, it developed and expanded its orientation and focus, staking its claim to a rightful place in the academic world. The first phase began in the late nineteenth century and led to an increase in the number of African American historians.[27] While the first generation mainly consisted of amateur historians, most of the second had received academic training. W. E. B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson were particularly influential in this process of professionalizing African American historiography.[28]

In 1915 Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH – now the ASALH) to promote Black history and historical scholarship by Blacks. In 1922 he established the first scholarly journal for African American history, the Journal of Negro History,[29] whose editorial board was integrated from the start. In 1926 he also established Negro History Week,[30] officially recognized by the American government as Black History Month[31] in 1976. Woodson’s aim was not only the celebration and visibility of Black history but also the gathering of documents and oral histories,[32] since libraries and archives, too, were deeply marked by or implicated in the perpetuation of racism and segregation.[33]

The primary aim of these historians was to boost the public image of Blacks and underscore their achievements and agency in the American nation’s rise to power.[34] In this manner African Americans have tried to assert control over their historical representation and their role in collective memory. Making the Black experience more visible was meant to help establish a form of “race pride” and to change “the black image in the white mind.”[35] Starting in the 1930s, a new generation of historians focused mainly on the relationship between Blacks and whites, since the former still suffered from limited educational and publication opportunities, not only in the South but all across the country.[36]

As the American civil rights movement continued to gain momentum after 1945, advocating equal rights and equal treatment, and as a growing number of African Americans began to attend college, the interest in African American history in general began to grow as well. By highlighting the marginalization of the African American experience and the formative influence of racism throughout American history and into the present, it was hoped that the current situation would improve. Starting in the 1960s, numerous colleges and universities established professorships and departments, if haltingly, or at least offered classes on African American history. The collective result was a boom in African American historical scholarship.[37]

Its propinquity to African American and Africana studies[38] has made African American history open to interdisciplinary work and new currents in historiography. Cultural-studies approaches are therefore not uncommon. The German historian Manfred Berg once referred to African American history as one of the “most important and most innovative fields of research.”[39] Categories and concepts such as gender, class, sexuality, transnationality or diaspora and their entanglement have quickly been adopted and further developed, often becoming a focal point of historical research.

Yet despite all the attention the subject received, publication opportunities were limited into the 1980s. For many years, the Journal of Negro History, which changed its name to the Journal of African American History relatively late in 2002, was the only periodical publishing rigorous articles on African American history.[40] Black scholars, in particular, seldom managed to publish articles on African American history in leading historical periodicals such as the Journal of American History[41] or the Journal of Southern History.[42] Bit by bit, however, they carved out a place for themselves in American historical studies and its journals.

The book-publishing industry, too, gradually reacted to the growing number of studies in African American history and established a range of publication series. Particularly noteworthy here is the John Hope Franklin Series in African American History and Culture brought out by the University of North Carolina Press, which for years has published outstanding work on African American history.[43] John Hope Franklin, who lent the series its name, was one of the most influential African American historians in the second half of the twentieth century.[44] In general, the American publishing industry, university presses included, has long been criticized for underrepresenting people of color.[45] Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU) have likewise played an underwhelming role in the market for academic publishing.[46]

Whereas it was initially mostly Black historians who concerned themselves with this broad topic, historians of other ethnic backgrounds and outside the United States have long devoted themselves to African American history as well. For years the subject has attracted great interest in Europe.[47] The field is increasingly popular in Britain.[48] The ties and historical parallels between Great Britain and the United States have led Robin D. G. Kelley and Stephen Tuck to speak about “the other special relationship” when it comes to race relations.[49] Historians from Germany, too, have for some time now contributed important and internationally acknowledged works on African American history.[50] Of particular interest here are transnational relations and the contacts between Germany and African American soldiers[51] during and after World War II as well as the ties between civil rights activists and artists.[52] Interdisciplinary approaches also play a role for German researchers. Silvan Niedermeier, for instance, uses visual history and postcolonial studies to take a critical look at the torture of African Americans at the hands of police in the American South.[53]

4. Research Focuses in African American Contemporary History

4.1 Civil Rights Movements

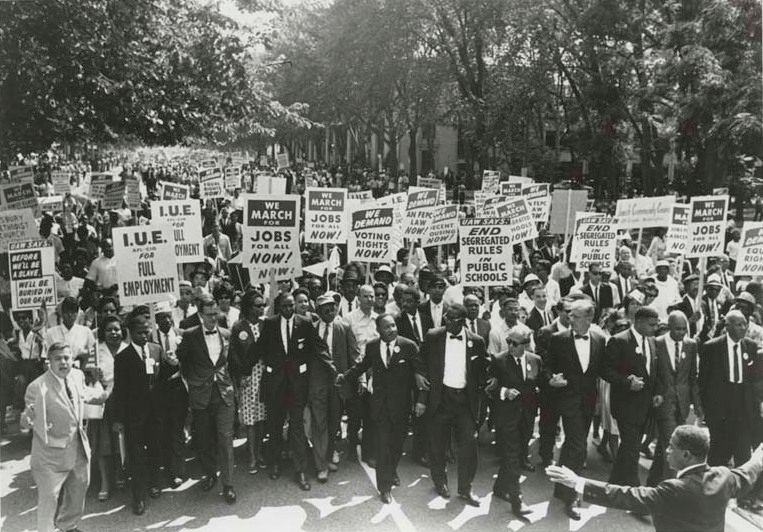

African American historiography has long centered on the experience of oppression, the struggle for freedom, and community building among the Black minority in the United States. In terms of contemporary history, the main focus is on the civil rights movement, its origin and differentiation since 1945. The struggle for integration and desegregation in all areas of life, the development of various tactics, from litigation through civil disobedience to armed resistance, have been treated by a multitude of works for a scholarly or general audience.[54] Biographies of Martin Luther King und Malcolm X were not just the center of media attention but were also well received in the academic world.[55]

Though African American contemporary history at the national level has revolved around political decisions and decision makers and never questioned their centrality, social history and the history of everyday life, especially from a regional perspective, have followed a bottom-up approach since the late 1970s. “Ordinary” people, often at the local level, have now increasingly become the focus.[56] This approach has challenged a range of basic assumptions in previous research on the nation’s civil rights movement, leading to a reassessment of local groups whose work was not always in line with the civil rights activists who garnered the media spotlight. For many historians, local activists such as Black churches and the NAACP, with their countless subgroups nationwide, were the main driving force behind nonviolent change.[57] Ideas, tactics and the individuals involved can also be investigated at the local level to see how they have changed over time or remained constant. It is these studies in particular that reveal the complex intersection between race, class and gender in the context of civil rights activism.[58] Moreover, a growing body of research shows how whites nationwide, in opposition to the manifold efforts of Blacks to achieve equality, have succeeded to the present day in preserving the extensive privileges and hierarchical structures of the white majority society.[59]

4.1.1 Timeframes

For many years, African American history focused on the heyday of the civil rights movement in the American South. This normally meant the period spanning from the 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional,[60] to the death of Martin Luther King in 1968. Since the 1990s, a growing number of historians have questioned this “traditional periodization”[61] of the civil rights movement and worked to expand its timeframe.[62]

The debate over expanding the chronological framework of the civil rights movement was intensified in 2005 with Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s essay “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” much discussed even outside the field of history.[63] Anchored in a profound critique of capitalism, she called for a positive reassessment of the contribution made by leftist and communist forces to the civil rights movement and the push for racial equality since the 1930s. Dowd Hall’s critique intensified the lively discussions taking place since the mid-1990s about the effects of the Cold War and communism/ anticommunism on the American civil rights movement, its strategy and social impact.[64] Though her call for broadening the chronological framework has generally been well received, it has not gone unchallenged. While the importance of the labor movement and the close correlation between race and class is hardly a matter of debate among serious historians,[65] some critics view her very positive assessment of leftist forces, especially the Communist Party of the United States, as an unwarranted romanticization of the communist left and an exaggeration of the role it played.[66] They point out the unique position of the civil rights movement after 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Civil Rights Act of 1964/68, Voting Rights Act of 1965), not least due to its character as a mass movement, and adhere to the division into phases despite ideological, individual and strategic continuities. Steven Lawson, actually one of the early proponents of broadening the temporal frame of reference, advocates differentiating between the “black freedom struggle” and the “civil rights movement,” beyond a mere semantic distinction. Historians, Lawson argues, have to better explore the differences and discontinuities, and thus convey a more nuanced picture of African American struggle and resistance against white oppression.[67] Critics have also pressed for a clearer definition of civil rights.[68]

Additionally, there are calls to focus on continuities and changes in the African American struggle for equal rights after 1968 rather than on the “supposedly hidden roots of the civil rights movement.”[69] The traditional interpretation sees a fundamental break with King’s civil rights movement and its nonviolent civil disobedience.[70] Other scholarly voices point to the link between the “traditional” civil rights movement and the Black Power era or to the long history of armed resistance in the African American fight for freedom. Rather than two contradictory movements, they see a “complex mosaic.”[71] They question a linear historical narrative in which one development or movement follows and builds on another.[72]

4.1.2 Places

There has also been a new geographical focus in the analysis of segregation and discrimination, the assessment of African American resistance and especially the civil rights movement after 1945. After an initial concentration on the Southern states and the fight for equal rights there, historians since the 2000s have shifted their attention to discrimination and civil rights struggles in the Northern and Western states. Only with this broadened perspective, they argue, can the civil rights movement and its impact on American life be truly understood,[73] as racism and discrimination were never just a problem in the American South but all across the nation.[74]

Broadening the focus to include the North and the West and hence viewing the race problem as a national one with international repercussions is fundamental to an understanding of the lives and experiences of African Americans and the perpetuation of the racial divide in the United States. No region of the country, research has shown, is free of racism and inequality, be it structural or individual. Only recently has Martin Luther King’s activism in the Northern states been examined more closely.[75] The Black Panther Party, moreover, actually originated in Oakland, California, where it fought against police brutality, housing shortages and social inequality.[76] Some studies suggest that the differences between the South and the rest of the country were “differences of degree” rather than “differences of kind”. Others argue that there was little notable distinction between the “de jure segregation” of the South and “de facto segregation” in the North.[77] A complete negation of differences, however, and the call for an “end of Southern history” are neither useful nor historically accurate.[78]

4.2 Women, Men, Gender and Sexuality

Black women and their role in society are meanwhile the subject of scholarly investigation in all areas of African American history. The rising feminist movement of the 1970s provided a new and important impetus in this direction. Black feminism, which did not go unnoticed by historians, pointed to the double discrimination of African American women, a fact both movements tended to ignore.[79] Black historians picked up on this idea and pointed out that neither African American history nor women’s history had sufficiently addressed the history of African American women.[80]

With a particular focus on regional actors, scholars began to map out the varied and complex roles and positions of women in the liberation and the civil rights movements,[81] their key role in church congregations and the African American community making them potent actors in the fight for equal rights.[82] Without working-class women and their long-standing activism, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-56 would never have happened or succeeded the way it did.[83] In the Black Power movement as well, despite all its male bravado, many women in addition to Angela Davis played a central role.[84]

A growing number of studies have addressed the multiple vulnerabilities of Black women within the system of white supremacy, but also in the Black community and the civil rights movement itself. The stigmatization of Black women as “welfare queens” and of Black families as dysfunctional and fatherless with consequences for social legislation have also been explored.[85] An analytical awareness of the entanglement of race, gender and sexuality but also of class is especially fruitful here. Research shows the crucial role of sexual violence against Black women, including rape, in the preservation of white supremacy as well as patriarchal and racist power structures.[86] And yet women are not reduced to the role of victims. Scholars look at the way Black women resisted the prevailing structures of dominance, made demands, and fought for their agency and freedoms.[87] They have also investigated exploitation at the hands of white women and the organization of Black women against their exploitation.[88]

The category of gender has entered African American history as well with the emergence of gender history. Explorations of the concept of femininity as well as masculinity have become a central theme. A growing number of studies have inquired into the meaning of masculinity and hypermasculine rhetoric in the African American community and the civil rights movement.[89] African American men experienced slavery, segregation and discrimination as a form of emasculation and sought to demonstrate their masculinity in a variety of ways as a result.[90] This often translated into sexism, misogyny and homophobia. Another important field of research is how civil rights movements and their leaders positioned themselves vis-à-vis strong women, feminism, the women’s liberation movement and especially the Black women’s liberation movement and hence how they reacted to shifting gender roles.[91]

More recently, historians have increasingly addressed the history of homosexuality in the African American community, especially during the civil rights movement. One of the first studies of a Black homosexual was John D’Emilio’s biography of Bayard Rustin, a close associate of A. Philip Randolph and Martin Luther King, Jr., who played a key if often overlooked role in organizing the March on Washington in 1963.[92] The first comprehensive biography of Pauli Murray, an important gay and transgender figure in American history, was published in 2020. As a Black lawyer and civil rights activist, she advocated equal rights for people of color as well as gender equality.[93]

In 2016, Kevin J. Mumford published his groundbreaking book Not Straight, Not White about the lifestyles, realities and protest movements of gay African Americans in the period between the March on Washington and the AIDS crisis.[94] Furthermore, in 2019, he was the editor of a special issue on “LGBT Themes in African American History” in the Journal of African American History.[95] Homosexuality, transsexuality and queerness in the African American community and their relationship to the civil rights movement are still in need of further research, however. Future studies might address the history of homophobia and homophobic rhetoric in the civil rights movement and the African American community, as well as critically examining the “investment in whiteness and middle-class identification” identified in the gay movement by historian Allan Bérubé.[96] Regional studies, with a focus outside the more familiar centers of activism like New York and San Francisco, would provide a more nuanced picture.

4.3 Black Internationalism

The international and transnational perspectives increasingly adopted by historians in recent years also play an important role in African American (contemporary) history.[97] A growing number of researchers view the civil rights movement and the formation of a Black and national identity within a larger transracial and international/ transnational framework. African Americans, after all, were not acting in a vacuum; they often thought in international or transnational terms, and sought to establish contacts with Africans but also with Latin and Asian Americans.[98]

Especially with regard to World War II and the Cold War,[99] an ever greater number of scholars are exploring the question of how the African American civil rights movement in all of its diversity positioned itself relative to American foreign policy and in particular to the global anticolonial movements and political developments in Asia and above all Africa.[100] Countless African Americans, studies show, were actively involved in these liberation movements, contributing on many levels and in many ways. Activists such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter White, Mary McLeod Bethune, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X and Angela Davis[101] engaged in varied anticolonial activities and sought a transnational exchange of experiences with people of color, in particular from Africa.

The Black Lives Matter movement, started in 2013, also sees itself as allied and working with people of color throughout the world.[102] The critique of capitalism also plays a prominent role in this context.[103] Following Dowd Hall, more recent research highlights leftist and communist activists who rebelled against colonialism, American capitalism and the Cold War. More liberal-minded voices in the civil rights movement have not fared well in this research driven by a general critique of capitalism.[104] With her book on the NAACP, Carol Anderson has reopened the discussion in the United States about the role of non-leftist liberal forces in the fight against colonialism.[105]

The importance of Africa as a point of reference and projection screen for the imagination is a subject of ongoing research, as is the association and cooperation with anticolonial groups and civil rights movements in African as well as Asian countries. South Africa under Apartheid and parallels to Jim Crow in the United States have increasingly attracted the attention of scholars.[106] That said, there has been little consensus to date among members of the African American community about their relationship to Africa as the continent of their ancestors. Moreover, the complex image of Africa among African Americans often turns out to be just as problematic and distorted as that of white Americans.[107] Newer studies have begun to focus on the multifaceted and often complicated relationship between African Americans and Asians at the national and transnational levels.[108]

4.4 (Police) Violence and Prisons

The number of inmates in American prisons rose from a half million in 1980 to two million in 2000.[109] This development, one that is unique in the world, has enabled the massive growth of the so-called prison-industrial complex, i.e., branches of the economy that profit from prisons through privatization, the provision of meals, the manufacturing of surveillance systems or cheap prison labor.[110] Prisons and related economic sectors have thus become a multi-billion-dollar business. African Americans are particularly affected by this development. In 2006, one in fourteen Black males in the United States was in jail, whereas the ratio for white males was 1:106.[111] In her pioneering study on the mass incarceration of Blacks, civil rights lawyer and activist Michelle Alexander described this as a continuation of the racist exclusion and discrimination under Jim Crow.[112]

Though historians have been slow to take an interest,[113] in the last ten years a range of books and essays has been published that critically engages with this topic as well as with related issues such as police surveillance and violence, criminalization, and protest movements in and outside of prisons, depicting these as formative elements of African American history since 1945. Studies on the history of the police and the American penal system provide further insights into the continued disenfranchisement and oppression of Blacks as well as the privileging of whites. Since their arrival in North America in the seventeenth century, African Americans have been criminalized, excessively policed and afforded inadequate police protection not only in the South.[114] Added to this are the countless, often deadly attacks on African Americans by white police officers as well as by civilians who see themselves as vigilante groups, attacks sometimes followed by protests and demands to reduce or abolish the police[115] and prisons.[116]

The phenomenon of lynching has been addressed by historians for some time now in this context. The Black Lives Matter movement and the press have used the term for contemporary cases of police violence – Trayvon Martin (2012), Breonna Taylor[117] and George Floyd (2020), among others. Since these deeds have mostly gone unpunished, the perpetrators being acquitted if charges were even filed at all, the academic and public discourse has made comparisons to the historical practice of lynching.[118] Individual studies on lynching, its significance and the trauma it poses for the African American community have appeared in recent years.[119]

Generally speaking, historians pinpoint Richard Nixon’s declaration of a “war on drugs”[120] in 1971 and the subsequent tightening of drug-related laws as the beginning of increased surveillance and the mass incarceration of Blacks in particular. Historians such as Elizabeth Hinton and Naomi Murakawa, however, point out that mass incarceration and police brutality have not only resulted from the regressive policies of conservative politicians, but also those of more liberal decision-makers, most notably Lyndon B. Johnson.[121] It was not rising crime rates, historians have argued, but Black demands for equal rights and social mobility as well as the fight against segregation that resulted in the successive criminalization and disenfranchisement of individuals belonging for the most part to minorities and the lower classes.[122] Historian Dan Berger explains how incarceration and the jailing of protestors in the South and the North were intended to crush the civil rights and Black Power movements. He also makes clear, however, that racially motivated prison sentences gave rise to new protest movements. Black freedom fighters used their own jailing to publicize locally, nationally and globally the inhumane conditions in prisons affecting people of color in particular.[123]

With books such as Black Silent Majority by Michael Javen Fortner, a number of authors have challenged the broad consensus on mass incarceration. It was sometimes African Americans, they write, who called for a greater police presence and harsher penalties for offenders, thus contributing to mass incarceration.[124] These studies indicate the importance of delving deeper into the various interests and motives of African Americans, the opportunities open to them as well as the influence of class.[125]

4.5 Culture of Remembrance

In 2016, the National Museum of African American History and Culture was opened on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the very heart of the nation’s memorial culture.[126] This was followed in April 2018 by the dedication of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, commemorating the racist terror of whites that has claimed the lives of thousands of Blacks.[127] While the suffering and resistance of African Americans is slowly becoming a part of America’s official collective memory, a sometimes violent controversy has flared up once again over the history and remembrance of the American Civil War, more specifically the statues and monuments to Confederates, giving rise to the question of what constitutes American history and identity.[128]

In 2019, to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved people in Virginia, the New York Times Magazine launched The 1619 Project with the aim of raising awareness of the fact that America and its rise to world power were deeply rooted in slavery, in the oppression of people of color, and racism. “No aspect of the country that would be formed here has been untouched by the years of slavery that followed. In the 400th anniversary of this fateful moment, it is finally time to tell our story truthfully.”[129] The project garnered widespread attention and praise but was also fiercely attacked, in particular by conservative forces, above all President Donald Trump.[130] Yet even established historians criticized its exaggerations and foreshortened perspective.[131]

In recent years, African American memorial culture has increasingly become the focus of public interest.[132] The overriding question is how events, lives and activists of the past have been and should be remembered and commemorated. Who commemorates what, and how and why do they do so? Which aspects of African American history, including the civil rights movement and its consequences, are commemorated collectively or individually – and which should or should not be? Who is behind these projects and who is featured in the narratives they produce? How have they been used for which purposes, political or otherwise? What does the culture of remembrance say about the American nation and the status of African Americans in the past and in the present?[133]

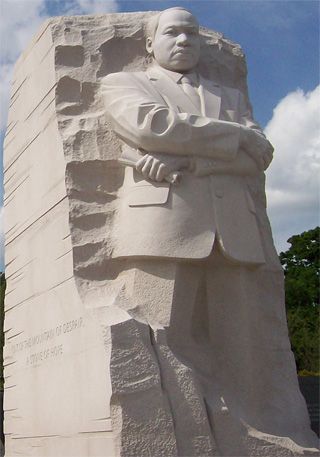

The 50th anniversary of the 1954 Supreme Court ruling on abolishing segregation in public schools, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the death of Rosa Parks in 2005, and the dedication of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial in 2011 all underscore the meaning of memory – and forgetting.[134] Rosa Parks, Esther Brown and Martin Luther King, Jr., are the key symbolic figures of nonviolent resistance and integration, representative of the moral victory not only of African Americans but of the entire nation. Yet their history is often simplified for the sake of expedience and to ensure that it fits the nation’s master narrative of unstoppable progress, democratic values, and American exceptionalism and superiority.[135]

Sculptor: Lei Yixin. Photo: Christine Knauer CC BY 3.0 DE

In her abovementioned essay “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” Jacquelyn Dowd Hall bemoans the functionalization and misuse of the civil rights movement, in particular by conservatives: “I want to make civil rights harder. Harder to celebrate as a natural progression of American values. Harder to cast as a satisfying morality tale. Most of all, harder to simplify, appropriate, and contain.”[136] Political scientist Jeanne Theoharis as well, in her biography of Rosa Parks, debunks the “national fable” of the tired seamstress who decided on a whim not to give up her seat on the bus.[137] Other myths and the politicization of African American history and its Black protagonists need to be explored as well, she argues. In general, historians have endeavored to highlight the problems of African American history, in particular the civil rights movement and its repercussions, presenting them in a more complex way in the nation’s collective memory.

5. Perspectives

The political and social legacy of slavery and segregation continues to weigh heavily on American society, which is far from the post-racial America frequently evoked during the presidency of Barack Obama with all of its highs and lows.[138] Following eight years under the country’s first Black president, the election of Donald J. Trump was a huge blow to liberals, especially for African Americans and minorities in general.

Already in 2013, the Supreme Court’s gutting of the 1965 Voting Rights Act made apparent the continued privileging of the white population and the vulnerability of minority rights.[139] The subsequent appointment of three conservative judges by President Trump shifted the Supreme Court noticeably to the right for generations to come. On July 1, 2021, it confirmed the autonomy of individual states and districts in shaping electoral law. Not only Black voters, but also Black politicians suffer from restrictions and oppression because of their skin color, as shown by George Derek Musgrove.[140] Continued police brutality against Blacks and the mishandling of protests by police in places like Ferguson, Baltimore and Milwaukee make clear how important it is to engage in an intensive study of Black history. America’s past and present cannot be understood without it.

Historians continue to investigate the consequences of structural racism and the opportunity gap, as well as the resistance of African Americans and their fight for agency. Specialized studies on the civil rights movement will further explore the diversity and radicality of various activists.[141] But there are many other areas of African American contemporary history in need of study that could ultimately speak volumes about race, politics,[142] the economy and/or activism.[143] Established fields of research such as labor and economic history, or more recent ones like military history,[144] continue to play an important role. Innovative work is emerging on the topics of space and architecture,[145] the insurance industry,[146] food and nutrition,[147] as well as recreation, travel and tourism.[148] A new perspective on African American history is also provided by emotional history.[149]

Contemporary history since the 1970s is likewise a field with many open questions. What became of the victories of the civil rights movement? How and at what levels is the civil rights movement still active? Which new forms of protest developed in the increasingly conservative political, social and cultural climate of the United States in the 1980s and afterwards? Ronald Reagan’s and Bill Clinton’s relationship to and policies towards the Black community and vice versa are also fruitful fields of inquiry for historians.[150]

The history of sickness and disability among African Americans has yet to be sufficiently explored. The coronavirus pandemic has made painfully clear how deeply rooted and entangled inequality is with race and class, not only in medicine but also on the labor market. Desegregation in medicine and the persistent racism there[151] as well as Black resistance[152] are being explored and linked to other fields of research, whereas a growing body of work has addressed medical care in the penal system.[153]

Closely linked to this, and an area with a lot of potential, is the field of environmental history. The water crisis in Flint, Michigan, is just one example of the multiple vulnerabilities of African Americans caused by systemic racism and inequality in housing,[154] services and environmental protection. Hurricane Katrina, too, made clear that Blacks are particularly affected by environmental factors and events.[155] By the same token, race plays a key role in climate change. Political decision-making along with African American experiences and activism at the individual, local and state levels also need to be more thoroughly investigated. How has the relationship to nature changed along lines of race, class and gender? What role have Blacks played in the environmental movement?[156]

The history of sports is another field of critical engagement, having long since left behind the notion that the achievements of Black athletes are an unambiguous cause for celebration.[157] Numerous studies have addressed the intersections of race, politics and capitalism in the sports world. Finally, a special issue of the Journal of African American History published in the spring of 2021 shows how the history of African American sports with its innovative approaches and subject matter has advanced and challenged the study of (African American) history.[158]

Other topics large and small will follow, challenging and enriching American history and its narratives. The diverse fields of research in African American history, its topics and lines of inquiry could ultimately help German contemporary historians focus more squarely on the entanglement of race, oppression and the struggle for freedom.

Translated from the German by David Burnett.

German Version: Afroamerikanische Geschichte / African American History, Version: 2.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 05.01.2022 https://docupedia.de/zg/Knauer_afroamerikanische_geschichte_v2_de_2022

References

[1] Robert L. Harris Jr., “Dilemmas in Teaching African American History,” in: Perspectives on History, November 1998, http://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/november-1998/dilemmas-in-teaching-african-american-history [10.06.2023].

[2] Jane H. Hill, The Everyday Language of White Racism, Malden, MA, 2008.

[3] See, e.g., Nancy Coleman, “Why We’re Capitalizing Black,” in: New York Times, July 5, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/05/insider/capitalized-black.html [10.06.2023]; “The Washington Post Announces Writing Style Changes for Racial and Ethnic Identifiers,” in: Washington Post, July 29, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/pr/2020/07/29/washington-post-announces-writing-style-changes-racial-ethnic-identifiers/ [10.06.2023].

[4] See, e.g., Cydney Adams, “Not All Black People Are African Americans. Here’s the Difference,” in: CBS News, June 18, 2020, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/not-all-black-people-are-african-american-what-is-the-difference/ [10.06.2023]; S. Ali, “Black or African American: Which Term You Should Be Using,” in: Reader’s Digest, April 2, 2021, https://www.rd.com/article/black-or-african-american-which-term-you-should-be-using/ [10.06.2023].

[5] Scholars have long discussed the emergence or invention of race and racism, often tracing it back to the beginning of the modern era. Historians such as Geraldine Heng, on the other hand, see its origins in the Middle Ages, whereas others trace it back as far as antiquity. Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, Cambridge 2018; Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Princeton 2004; Denise Eileen McCoskey, Race: Antiquity & its Legacy, Oxford/New York 2013.

[6] While Blackness has long been understood and analyzed as a construct, it is only in the last twenty years or so that whiteness studies has concerned itself with the analytical category of whiteness, asking “how diverse groups in the United States came to identify, and be identified by others, as white – and what that has meant for the social order.” Peter Kolchin, “Whiteness Studies: The New History of Race in America,” in: Journal of American History 89 (2002), no. 1, 154-173, here 155, online at http://www.cwu.edu/diversity/sites/cts.cwu.edu.diversity/files/documents/whiteness.pdf [10.06.2023]; Gary Gerstle, American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, Princeton 2001. A selection of major works in whiteness studies: Noel Ignatiev, How the Irish Became White, New York 1995; Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890-1940, New York 1998; David R. Roediger, Working toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White – The Strange Journey from Ellis Island to the Suburbs, New York 2005; Nell Irvin Painter, The History of White People, New York 2010.

[7] On the history of race, see, e.g., Michael James, “Race,” in: Edward N. Zalta (ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford 2012, http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2012/entries/race/ [10.06.2023]; C. Loring Brace, “Race” Is a Four-Letter Word: The Genesis of the Concept, New York 2005. A transnational look at racism is offered by Simon Wendt, “Transnational Perspectives on the History of Racism in North America,” in: Amerikastudien/American Studies 54 (2009), no. 3, 473-498.

[8] Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York 2016. The Western notion of “freedom” being created by and for whites is discussed in Tyler Stovall, White Freedom: The Racial History of an Idea, Princeton 2021.

[9] AG Queer Studies (ed.), “Einleitung,” in: Verqueerte Verhältnisse: Intersektionale, ökonomiekritische und strategische Interventionen, Hamburg 2009, 15.

[10] James Q. Whitman asserts that the Nazi “race laws” were based on those of the United States. James Q. Whitman, Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, Princeton 2017.

[11] See, e.g. Norbert Finzsch, “Wissenschaftlicher Rassismus in den Vereinigten Staaten – 1850 bis 1930,” in: Heidrun Kaupen-Haas/Christian Saller (eds.), Wissenschaftlicher Rassismus: Analysen einer Kontinuität in den Human- und Naturwissenschaften, Frankfurt a.M. 1999, 84-110, here 84-86; Helga Amesberger/Brigitte Halbmayr, “Race/ 'Rasse' und Whiteness – Adäquate Begriffe zur Analyse gesellschaftlicher Ungleichheit?”, in: L’Homme: Europäische Zeitschrift für feministische Geisteswissenschaften 16 (2005), no. 2, 135-143, online https://lhomme-archiv.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/p_lhomme_archiv/PDFs_Digitalisate/16-2-2005/lhomme.2005.16.2.135.pdf [10.06.2023].

[12] Historians have addressed German colonialism and the issue of race for some time now, including controversial discussions of the relationship between the Holocaust and colonial racism and violence. See Jürgen Zimmerer, Von Windhuk nach Auschwitz. Beiträge zum Verhältnis von Kolonialismus und Holocaust, Münster 2011; Benjamin Madley, “From Africa to Auschwitz: How German South West Africa Included Ideas and Methods Adopted and Developed by the Nazis in Eastern Europe,” in: European History Quarterly 33 (2005), 429-464.

[13] Paul Finkelman, Slavery and the Founders: Race and Liberty in the Age of Jefferson, Armonk, NY 1996; Lawrence Goldstone, Dark Bargain: Slavery, Profits, and the Struggle for the Constitution, New York 2005.

[14] See, e.g., Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863, Chicago 2003. “Slave-free” regions also profited from the slave trade and slavery, e.g., by processing cotton in textile mills, see, e.g., Leonardo Marques, The United States and the Transatlantic Slave Trade to the Americas, 1776-1867, New Haven 2016; on the links between slavery, exploitation and capitalism, see Sven Beckert/Seth Rockman (eds.), Slavery’s Capitalism A New History of American Economic Development, Philadelphia 2016; Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, New York 2015.

[15] On the origins of slavery in the colonies and the United States, see, e.g., Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, Cambridge 1998; idem, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves, Cambridge 2003; Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman? Female Slaves in the Plantation South, New York 1999; Stephen R. Haynes, Noah’s Curse: The Biblical Justification of American Slavery, New York 2002; on the fight for civil rights before the Civil War: Kate Masur, Until Justice Be Done: America’s First Civil Rights Movement from the Revolution to Reconstruction, New York 2021.

[16] See, e.g., Henry Kamerling, Capital and Convict: Race, Region, and Punishment in Post-Civil War America, Charlottesville 2019; Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, New York 2008.

[17] Michael J. Klarman, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality, New York 2004; Blair L. M. Kelley, Right to Ride: Streetcar Boycotts and African American Citizenship in the Era of Plessy v. Ferguson, Chapel Hill 2010; Barbara Y. Welke, “When All the Women Were White, and All the Blacks Were Men: Gender, Class, Race, and the Road to Plessy. 1855-1914,” in: Law and History Review 13 (1995), no. 2, 261-316; Charles A. Lofgren, The Plessy Case: A Legal-Historical Interpretation, New York 1987.

[18] On lynching, see, e.g., W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930, Chicago 1993; William D. Carrigan (ed.), Lynching Reconsidered: New Perspectives in the Study of Mob Violence, New York 2007; Michael J. Pfeifer, Rough Justice: Lynching and American Society, 1874-1947, Chicago 2004; idem, The Roots of Rough Justice: Origins of American Lynching, Chicago 2011; Manfred Berg, Lynchjustiz in den USA, Hamburg 2014.

[19] For an overview of the situation for African Americans after the Civil War, see, e.g., Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917, Chicago 1995; Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, New York 1999; Joel Williamson, “The Crucible of Race: Black-White Relations in the American South since Emancipation, New York 1984. An example of how it was challenged: W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Roar on the other Side of Silence: Black Resistance and White Violence in the American South, 1880-1940,” in: idem (ed.), Under the Sentence of Death: Lynching in the South, Chapel Hill 1997, 271-291.

[20] Jeffrey Aaron Snyder, Making Black History: The Color Line, Culture, and Race in the Age of Jim Crow, Athens 2018, 3.

[21] On African historiography and the writing of African history, see John Edward Philips (ed.), Writing African History, Rochester 2005.

[22] Heather Andrea Williams, Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom, Chapel Hill 2005.

[23] Daniel J. Crowley (ed.), African Folklore in the New World, Austin 1977; Lawrence W. Levine, Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom, New York 1977. On African American historiography, see Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, African American History Reconsidered, Urbana 2010; idem, What Is African American History?, Malden, MA, 2015; John Ernest, Liberation Historiography: African-American Writers and the Challenge of History, Chapel Hill 2004; Stephen G. Hall, A Faithful Account of the Race: African American Historical Writing in Nineteenth Century America, Chapel Hill 2009; William D. Wright, Black History and Black Identity: A Call for a New Historiography, Westport 2002.

[24] Patricia Morton, Disfigured Images: The Historical Assault on Afro-American Women, New York 1991.

[25] Geneviève Fabre/Robert O’Meally (eds.), History and Memory in African-American Culture, Cary, NC, 1994; bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston 1992; W. Fitzhugh Brundage, The Southern Past: A Clash of Race and Memory, Cambridge 2005.

[26] Sterling Lecater Bland, Jr., African American Slave Narratives: An Anthology Volume I, Westport 2001.

[27] On early African American historians and their experiences with sexism and racism, see chapter 4 “Ample Proof of this May Be Found: Early Black Women Historians,” in: Dagbovie, African American History Reconsidered, 99-127. A collection of personal narratives by contemporary historians can be found in Deborah Gray White, Telling Histories: Black Women Historians in the Ivory Tower, Chapel Hill 2008.

[28] Du Bois was the first Black man to earn his doctorate from Harvard. His career as both a sociologist and a historian spanned three of the four generations identified by Franklin. See W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches, Chicago 1903; idem, Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880, New York 1935. Woodson also got his doctorate from Harvard.

[29] The Negro History Bulletin, today’s Black History Bulletin, was founded in 1937. Its intended readership was elementary- and secondary-school teachers. https://asalh.org/document/the-black-history-bulletin/ [10.06.2023].

[30] On Woodson see Pero Gaglo Dagbovie, Carter G. Woodson in Washington D.C., Charleston 2014; Brenda E. Stevenson, “'Out of the Mouths of Ex-Slaves': Carter G. Woodson’s Journal of Negro History 'Invents' the Study of Slavery,” in: Journal of African American History 100 (2015), no. 4, 698-720; Jarvis R. Givens, “'There Would Be No Lynching If It Did Not Start in the Schoolroom': Carter G. Woodson and the Occasion of Negro History Week, 1926-1950,” in: American Educational Research Journal 56 (2019), no. 4, 1457-1494.

[31] Black History Month has also long been the subject of criticism. Parts of the Black Power movement in the 1970s organized a Black Liberation Week, others an African Heritage Month. See Dagbovie, Reclaiming the Black Past, 54. Its commercialization has also been increasingly criticized, with some expressing their concern that the actual intention behind the observance and the ongoing oppression of Black people in the United States have largely been forgotten in the process. See, e.g., “The Commercialization of Black History Month,” in: Black Youth Project, 08.02.2012, online http://blackyouthproject.com/the-commercialization-of-black-history-month/ [10.06.2023]; Doreen St. Félix, “The Farce, and the Grandeur, of Black History Month under Trump,” in: New Yorker, February 2, 2018, online https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-farce-and-the-grandeur-of-black-history-month-under-trump [10.06.2023].

[32] Dagbovie, Carter G. Woodson in Washington, D.C., 31; Snyder, Making Black History.

[33] See, e.g., Wayne A. and Shirley A. Wiegand, The Desegregation of Public Libraries in the Jim Crow South: Civil Rights and Local Activism, Baton Rouge 2018; Alex H. Poole, “The Strange Career of Jim Crow in the Archives. Race, Space, and History in the Twentieth-Century American South,” in: American Archivist 77 (2014), no. 1, 23-63; Rabia Gibbs, “The Heart of the Matter: The Developmental History of African American Archives,” in: American Archivist 75 (2012), no. 1, 195-204. Particularly important are the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York City (part of the New York Public Library system), the National Archives in Washington, D.C., which includes the archived documents of the NAACP, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University (Washington, D.C.) and the archive of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

[34] V. P. Franklin, the former editor of the Journal of African American History, calls this “contributionism.” Idem, “Introduction: Symposium on African American Historiography,” in: Journal of African American Life and History 92 (2007), no. 2, 214-17, here 214. The journal’s new editor since January 2019, Pero Dagbovie, has dealt extensively with Black history; see above and idem, Reclaiming the Black Past: The Use and Misuse of African American History in the Twenty-First Century, New York 2018.

[35] The title of a book by George M. Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind. The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914, New York 1971.

[36] John Hope Franklin, “On the Evolution of Scholarship in Afro-American History,” in: Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (ed.), The Harvard Guide to African-American History, Cambridge 2001, XXI-XXX. W.D. Wright identifies only three generations of African American historians: W. D. Wright, Black History and Black Identity: A Call for a New Historiography, Westport 2002, 33. Unlike Franklin and Wright, John Ernest refers to African American historians who were active before the end of the Civil War writing “liberation historiography”: John Ernest, “Liberation Historiography: African-American Historians before the Civil War,” in: American Literary History 14 (2002), no. 3, 413-443.

[37] On the development of these departments, see Martin Kilson, “From the Birth to a Mature Afro-American Studies at Harvard, 1969-2002,” in: Lewis R. Gordon/Jane Anna Gordon (eds.), A Companion to African American Studies, Malden, MA, 2006, 59-75. Lara Leigh Kelland shows the importance of grassroots movements in establishing archives and in public history: Lara Leigh Kelland, Clio’s Foot Soldiers: Twentieth-Century US Social Movements and Collective Memory, Amherst 2018.

[38] The focus in African American studies is on the history and culture of the African diaspora in America. Africana studies, on the other hand, addresses African culture and the culture of the African diaspora from antiquity to the present. Roquinaldo Ferreira, “The Institutionalization of African Studies in the United States: Origin, Consolidation and Transformation,” in: Revista Brasileira de História 30 (2010), no. 59, 71-88, online http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbh/v30n59/en_v30n59a05.pdf [10.06.2023].

[39] Manfred Berg, Geschichte der USA, Munich 2013, 141.

[40] Nowadays there are a range of journals focused on African American/Black Studies, including the Journal of African American Studies, the Journal of Black Studies, the Western Journal of Black Studies, Afro-Americans in New York Life and History and Souls. The following historical journals contain a large number of articles and reviews dedicated to African American history: the Journal of American History, the Journal of Southern History and the Journal of Civil and Human Rights. The German publication Amerikastudien / American Studies also brings numerous articles and reviews on African American history and culture.

[41] In 1945, Benjamin Quarles became the first African American historian to publish in the Mississippi Valley Historical Review, which was founded in 1914 and now goes by the name Journal of American History.

[42] On the emergence of the Journal of African American History, see Jacqueline Goggin, “Countering White Racist Scholarship. Carter G. Woodson and The Journal of Negro History,” in: Journal of Negro History 68 (1983), 355-375.

[43] Other publishing houses have their own series on Black studies, such as the New Black Studies Series of University of Illinois Press, under editors Darlene Clark Hine and Dwight A. McBride: https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/find_books.php?type=series&search=NBS [10.06.2023]. And New York University Press has recently launched its Black Power Series under the editorship of Ashley D. Farmer und Ibram X. Kendi, https://www.blackpowerseries.com/ [10.06.2023].

[44] Franklin, who died in 2009 at the age of 94, had always combined his research with civil-rights activism. His book From Slavery to Freedom, originally published in 1947, is still considered a key work of African American history and is now in its tenth revised edition. John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, 1st ed. New York 1947. His autobiography, published in 2005, sheds light on the development of African American historiography and the civil rights movement. Idem, Mirror to America: The Autobiography of John Hope Franklin, New York 2005. Still a significant work: C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, New York 1955.

[45] Lee and Low Books, Where is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2019 Diversity Baseline Survey Results, https://blog.leeandlow.com/2020/01/28/2019diversitybaselinesurvey/ [10.06.2023]; “'A Conflicted Cultural Force': What It’s Like to Be Black in Publishing,” in: New York Times, July 1, 2020; Association of University Presses, Statement on Equity and Anti-Racism, March 2020, https://aupresses.org/about-aupresses/equity-and-antiracism/ [10.06.2023].

[46] In March 2021, Howard University, which from 1972 to 2011 had its own publishing arm, announced a collaborative venture with Columbia University Press. The cooperation and the launching of a new series entitled “Black Lives in the Diaspora: Past / Present / Future” are intended to contribute to research in the field as well as giving a fair chance to graduates of HBCUs. See “Howard University Partners with Columbia University Press to Advance Black Studies and Diversify Academic Publishing,” in: Newsroom Howard University, March 3, 2021, https://newsroom.howard.edu/newsroom/article/13956/howard-university-partners-columbia-university-press-advance-black-studies-and [10.06.2023].

[47] On the international interest in American and African American history, see Nicolas Barreyre/Michael Heale/Stephen Tuck/Cécile Vidal (eds.), Historians across Borders: Writing American History in a Global Age, Berkeley 2014; Wendt, Transnational Perspectives on the History of Racism in North America.

[48] Representative for British research on African American contemporary history and relations between Blacks and whites in the South are the works of Stephen Tuck, Ben Houston and Clive Webb: Stephen Tuck, The Night Malcolm X Spoke at the Oxford Union. A Transatlantic Story of Antiracist Protest, Berkeley 2014; Benjamin Houston, The Nashville Way: Racial Etiquette and the Struggle for Social Justice in a Southern City, Athens, GA 2012; Clive Webb, Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights, Athens 2001.

[49] Robin D. Kelley/Stephen Tuck (eds.), The Other Special Relationship: Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the USA, New York 2015.

[50] Eva Boesenberg, “Reconstructing 'America': The Development of African American Studies in the Federal Republic of Germany,” in: Larry A. Greene/Anke Ortlepp (eds.), Germans and African Americans: Two Centuries of Exchange, Jackson 2011, 218-230. For German research on African American history, see, e.g., Manfred Berg, The Ticket to Freedom: Die NAACP und das Wahlrecht der Afro-Amerikaner, Frankfurt a.M. 2000; Simon Wendt, The Spirit and the Shotgun: Armed Resistance and the Struggle for Civil Rights, Gainesville 2007; Norbert Finzsch/James Oliver Horton/Lois E. Horton, Von Benin nach Baltimore: Die Geschichte der African Americans, Hamburg 1999; Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson, GegenSpieler: Martin Luther King – Malcolm X, Frankfurt a.M. 2000; Jürgen Martschukat, “'Little Short of Judicial Murder': Todesstrafe und Afro-Amerikaner, 1930-1972,” in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft 30 (2004), no. 3, 490-526; Anke Ortlepp, Jim Crow Terminals: The Desegregation of American Airports, Athens 2017. The following German universities (listed in alphabetical order) are notably strong in African American history: Augsburg (Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson), FU Berlin, Bochum (Rebecca Brückmann), Erfurt (Jürgen Martschukat and Silvan Niedermeier), Frankfurt am Main (Simon Wendt), Heidelberg (Manfred Berg), Cologne (Anke Ortlepp).

[51] Maria Höhn/Martin Klimke, A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany, New York 2010.

[52] Maria Schubert, “We Shall Overcome.” Die DDR und die amerikanische Bürgerrechtsbewegung, Paderborn 2018; Sophie Lorenz, “Schwarze Schwester Angela:” – Die DDR und Angela Davis: Kalter Krieg, Rassismus und Black Power 1965-1975, Bielefeld 2020.

[53] Silvan Niedermeier, “Violence, Visibility, and the Investigation of Police Torture in the American South, 1940-1955,” in: Jürgen Martschukat/Silvan Niedermeier (eds.), Violence and Visibility in Modern History, New York 2013, 91-111; idem, Rassissmus und Bürgerrechte: Polizeifolter im Süden der USA 1930-1955, Hamburg 2014; English translation: The Color of the Third Degree: Racism, Police Torture, and Civil Rights in the American South, 1930-1955, Chapel Hill 2019; Philipp Dorestal, Style Politics: Mode, Geschlecht und Schwarzsein in den USA, 1943-1975, Bielefeld 2012.

[54] An overview of the state of research is provided by Kevin Gaines, “African-American History,” in: Eric Foner/Lisa McGirr, American History Now, Philadelphia 2011, 400-420. Numerous encyclopedias have been published in recent years, see, e.g., Paul Finkelman (ed.), Encyclopedia of African American History 1896 to the Present, New York 2009; Colin A. Palmer (ed.), Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History: The Black Experience in the Americas, New York 2005; Robert L. Harris Jr./Rosalyn Terborg-Penn (eds.), The Columbia Guide to African American History since 1939, New York 2006. Overviews of African American history with varied chronological perspectives and assessments of the historical protagonists: Stephen Tuck, We Ain’t What We Ought to Be: The Black Freedom Struggle from Emancipation to Obama, Cambridge 2010; Thomas C. Holt, Children of Fire: A History of African Americans, New York 2001; Manning Marable, Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982, Jackson 1984; Harvard Sitkoff, The Struggle for Black Equality, 1954-1992, New York 1993; Philip A. Klinkner/Rogers M. Smith, The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America, Chicago 1999; Jonathan Holloway, The Cause of Freedom: A Concise History of African Americans, Oxford 2021.

[55] David L. Lewis, King: A Critical Biography, New York 1970. A wide variety of biographies and research on King and Malcolm X have since emerged, including a multi-volume biography and social study of King: Taylor Branch, America in the King Years, 3 vols., New York 1988/1998/2006. Manning Marable’s work on Malcolm X published in 2011 was the subject of heated debate: Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, New York 2011. An overview of Malcolm’s X’s international significance is provided by Tuck, The Night Malcolm X Spoke at the Oxford Union. Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson published a study on King and Malcolm X in the year 2000 and a German biography of Malcolm X in 2015: Waldschmidt-Nelson, GegenSpieler; idem, Malcolm X: Der schwarze Revolutionär, Munich 2015. A host of more recent studies investigates aspects of activism and the lives of well-known civil rights activists, e.g., Gary Dorrien, Breaking White Supremacy. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Black Social Gospel, New Haven 2018.

[56] Steven F. Lawson, “Freedom Then, Freedom Now: The Historiography of the Civil Rights Movement,” in: American Historical Review 96 (1991), no. 2, 456-471, here 457.

[57] See esp. John Dittmer, Local People: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi, Champaign, Ill, 1995; Charles M. Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, Berkeley 1995.

[58] Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Princeton 1996; Bryant Simon, A Fabric of Defeat: The Politics of South Carolina Millhands, 1910-1948, Chapel Hill 1998; Stephen Tuck, Beyond Atlanta: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Georgia, 1940-1980, Athens 2001.

[59] Clive Webb (ed.), Massive Resistance: Southern Opposition to the Second Reconstruction, New York 2005; Jason Morgan Ward, Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936-1965, Chapel Hill 2011; Carol Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide, New York 2016. Zur Rolle von Frauen: Elizabeth Gillespie McRae, Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy, Oxford 2018; Rebecca Brückmann, Massive Resistance and Southern Womanhood: White Women, Class, and Segregation, Athens 2021. See also Stephanie Jones-Rogers, They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South, New Haven 2019.

[60] See, e.g., Michael J. Klarman, Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement, New York 2007; James T. Patterson, Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy, New York 2001; Anders Walker, The Ghost of Jim Crow: How Southern Moderates Used Brown v. Board of Education to Stall Civil Rights, New York 2009; Sonderhefte zu Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka: Journal of American History 9 (2004), no. 3; Fifty Years of Educational Change in the United States, 1954-2004: Journal of African American History 90 (2005), no. 1/2; Joseph Bagley, The Politics of White Rights: Race, Justice, and Integrating Alabama’s Schools, Athens 2018.

[61] Glenn Feldman (ed.), Before Brown: Civil Rights and White Backlash in the Modern South, Tuscaloosa 2004, 1. As early as 1968, historian Richard M. Dalfiume referred to the period between the Second World War and the Brown ruling as “the forgotten years of the Negro Revolution.” Richard M. Dalfiume, “The 'Forgotten Years' of the Negro Revolution,” in: Journal of American History 55 (1968), no. 1, 90-106, online http://hutchinscenter.fas.harvard.edu/sites/all/files/Dalfiume%20-%20Forgotten%20Years%20of%20the%20Negro%20Revolution.pdf [10.06.2023].

[62] Leon F. Litwack, “'Fight the Power!' The Legacy of the Civil Rights Movement,” in: Journal of Southern History 75 (2009), no. 1, 3-28, here 3; cf. Vincent Harding, There Is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America, New York 1981.

[63] Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” in: Journal of American History 91 (2005), no. 4, 1233-1263, online http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/ows/seminars/tcentury/movinglr/longcivilrights.pdf [10.06.2023]. Similar conclusions are reached by Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919-1950, New York 2008; Robin D. G. Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists during the Great Depression, Chapel Hill 1990; Robert Rodgers Korstad, Civil Rights Unionism: Tobacco Workers and the Struggle for Democracy in the Mid-Twentieth-Century South, Chapel Hill 2003; Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North, New York 2008; Martha Biondi, To Stand and Fight: The Struggle for Civil Rights in Postwar New York City, Cambridge 2003.

[64] On the relationship between the Cold War and the civil rights movement, see Brenda Gayle Plummer, Rising Wind: Black Americans and U.S. Foreign Affairs, 1935-1960, Chapel Hill 1996; John David Skrentny, “The Effect of the Cold War on African-American Civil Rights: America and the World Audience, 1945-1968,” in: Theory and Society 27 (1998), 237-285; Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy, Princeton 2000; Berg, The Ticket to Freedom.

[65] Kevin Boyle, “Labor, the Left and the Long Civil Rights Movement,” in: Social History 30 (2005), no. 3, 366-372.

[66] Critics point out that, by the late 1930s, the CPUSA was subordinate to the Soviet CP and followed its orders. Eric Arnesen, “Reconsidering the 'Long Civil Rights Movement',” in: Historically Speaking 10 (2009), no. 2, 31-34; idem, “No 'Grave Danger': Black Anticommunism, the Communist Party, and the Race Question,” in: Labor: Studies in Working-Class History of the Americas 3 (2006), no. 4, 13-52; idem, “Civil Rights and the Cold War at Home. Postwar Activism, Anticommunism, and the Decline of the Left,” in: American Communist History 11 (2012), no. 1, 5-44.

[67] Steven F. Lawson, “Long Origins of the Short Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1968,” in: Danielle L. McGuire/John Dittmer (eds.), Freedom Rights: New Perspectives on the Civil Rights Movement, Lexington 2011, 9-38, esp. 25-27; Berg, Geschichte der USA, 145.

[68] Sundiata K. Cha-Jua/Clarence E. Lang, “The 'Long Movement' as Vampire: Temporal and Spatial Fallacies in Recent Black Freedom Studies,” in: Journal of African American History 92 (2007), no. 2, 265-288. More recent publications call for a more detailed look at the changing legal definitions and the general understanding of civil rights. See, e.g., Christopher W. Schmidt, “Legal History and the Problem of the Long Civil Rights Movement,” in: Law and Social Inquiry 41 (Fall 2016), 1081-1107, here 1082; Dylan C. Penningroth, “Everyday Use: A History of Civil Rights in Black Churches,” in: Journal of American History 107 (March 2021), 871-898.

[69] Berg, Geschichte der USA, 145.

[70] On the long prehistory of civil disobedience, see most recently Anthony C. Siracusa, Nonviolence before King: The Politics of Being and the Black Freedom Struggle, Chapel Hill 2021. For a critical reassessment and repositioning of civil disobedience, see Erin R. Pineda, Seeing like an Activist: Civil Disobedience and the Civil Rights Movement, Oxford 2021.