Publikationsserver des Leibniz-Zentrums für

Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam

e.V.

Archiv-Version

Heimat (english version)

Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 13.08.2018 https://docupedia.de/jaeger_heimat_v1_en_2018

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.2.1192.v1

Heimat again? It’s back in fashion, no doubt about it. All throughout the German-speaking world, and not just in academia, people have been talking about it. The word is ubiquitous, an everyday occurrence, equally present in the media, advertising, public relations and politics. German history is virtually saturated with it, from the nineteenth century and the German Empire, to the Weimar Republic and the Nazi period, into the postwar years of Germany West and East (but also in Austria and Switzerland). It is found in völkisch-chauvinist movements as a counter-concept to modernity and everything deemed “foreign,”[1] but also in the vocabulary of leftists – for instance, on local campaign posters of the KPD from the 1950s: “Münchner schützt die Heimat vor neuer Zerstörung” (People of Munich, protect the homeland from renewed destruction!).[2] Willy Brandt mentioned Heimat multiple times in a government declaration of January 18, 1973, emphasizing that Germans were looking for “a home [Heimat] in society that admittedly will never be idyllic again – if ever it was to begin with.” The precondition to this, he said, was “freedom in everyday life,” in which “the citizen should find his social and spiritual home [Heimat].”[3] Brandt used the term in conjunction with everyday life and the notions of self-determination, security and neighborliness; he did not equate the state with Heimat, as cultural anthropologist Ina-Maria Greverus pointed out in 1979. He “spoke about a Heimat to be created by citizens within the state, within society, and did not use Heimat in its affirmative sense equivalent to the state,” she wrote.[4] In this sense the word appears to be a household term, a contentious one that lends itself to political and ideological usage and that looks back on a varied history that is always open to new interpretations.

The KPD does use the word Heimat, but on the other hand conjures up an urban symbol of Munich with a photograph of the Frauenkirche soon after the war, along with some photos of local tenement buildings. The lower image depicts Karl-Marx-Allee in East Berlin, a prestige project of urban architecture in the early GDR. Heimat is linked here to urban spaces, and the lower photo is in keeping with the socialist concept of Heimat, emphasizing the active creation of space by the working class.

KPD poster: “People of Munich, protect the homeland!,” KPD (Munich), 1960s. Source: Bundesarchiv Plak 005 - Bundesrepublik Deutschland I (1949-1966), Plak 005-026-035 © courtesy of the German Federal Archives

Political groups from left to right lay claim to the concept of Heimat. Heimat can be used in conjunction with many phenomena and sometimes seems to have a precise definition. Its use has the effect of scaling things down or making certain issues more accessible or imaginable, more pleasant or human. The very vagueness of the concept bespeaks its emotional aspect, one that makes it rather appealing for a wide range of marketing and propaganda purposes. Why is this so? Why does the term go in and out of fashion, and why is it often invoked by conservative forces in particular? Granted, the political left, even the extreme left, has grappled with the concept as well. It’s a term, at any rate, that has long been a part of everyday language.

Apparently Heimat serves as a focal point of identity processes which in view of modernization, crises and globalization have offered the individual a stable locus within a complex yet manageable sociocultural and spatial set-up. Heimat denotes a local identification that is not exclusive of other identifications, whether regional, national or transnational institutions, ideologies or religious communities.

Heimat is hence a kind of basic unit that is available on demand whenever larger units are endangered or begin to unravel. This was strikingly evident in the German-speaking world after 1945. Not only did it serve to reinvest an immediate living environment with meaning, for better or for worse; it was virtually courted on multiple occasions by massive population shifts and political upheavals – as evidenced by the success of the West German Heimatfilm.[5] A socialist concept of Heimat even developed in the German Democratic Republic, contrary to an initial and fundamental rejection of the concept, which was thought to be conservative and bourgeois.[6]

And yet the concept of homeland itself, expressed in the German-speaking world as Heimat, is by no means a purely German phenomenon. The supposed lack of a corresponding term in other languages has often been taken as an indication that the concept is unique to this part of the world. But this view has been subject to increasing criticism.[7] In psychology as well as in certain quarters of cultural anthropology, the concept of homeland / Heimat is considered a fundamental principle of human identity.[8] It describes a network of relationships that positions individuals in social groups at a local, regional, national and global level. It can also be used to express a basic concept of modern socialization, regardless of the cultural and linguistic region it refers to. In scholarship, however, this basic concept seems to refer exclusively to the German-speaking Heimat, because only in the German-speaking world has such a word served as a rallying point.

The following will address the concept and its varied meanings, and this in considerable detail given the importance attached to it by previous generations of historians. But it will also examine the fundamental relationship between individuals with respect to their social and geographic spaces – the relationship determining the locus of the individual within the fabric of society, lending meaning to his immediate surroundings while at the same time enabling his integration into larger units. Homeland is a concept of general significance to modernization processes, capable as it is of integrating various claims to loyalty.

It is therefore essential when analyzing historical trends to look beyond the German-speaking world and investigate whether the term Heimat or, rather, the phenomenon of homeland does not have a structuring and heuristic value that describes a constitutive subnational and subregional phenomenon of modernity, one capable of integrating larger groups over longer periods of time in a small-scale and emotionally appealing manner, hence offering the individual a place to develop and feel secure. Whether the German word Heimat is useful in this regard remains an open question for now. Ina-Maria Greverus speaks of “territoriality,”[9] Alon Confino has coined the term “Heimatism”[10] with reference to modern German history, whereas David Blackbourn and James Retallack have opted for “localism”[11] as a guiding concept. The German-language discourse on Heimat could therefore be viewed as a specific case, and the more fundamental concept of homeland (territoriality or Heimatism) as a basic phenomenon of modernity. And yet research on the German-speaking world is particularly rich, and its findings could, in principle, be put to good use to expand the horizons of local, regional or global historiography.

The postcard shows a typical motif: the view of a town with a church in the middle embedded in a landscape depicting woods, fields, hills and water. The picture is colorized, underscoring contemporary notions of the aesthetic and natural character of the scene. Such scenes are not just typical of German postcards but were common around the world at the turn of the twentieth century. The postcard was an everyday form of communication, not made and sold for tourists alone but popular among locals as well.

Photographic postcard, colorized: “Ratzeburg v. Drei Linden” ca. 1905 /1906, Verlag Ottmar Zieher, Munich 8.8 x 14 cm, postmarked July 18, 1906. Source: Private collection of J. Jäger, with kind permission

The Conceptual History of Heimat

It cannot be our goal as historians to provide a universal definition of Heimat, for, indeed, it is much too closely tied to certain historical-cultural configurations. It is therefore essential to begin by historicizing the discourse on Heimat. Moreover, a framework must be established to enable an understanding of how the concept was used in specific periods and contexts.[12] Second, the phenomenon needs to be grasped independently of the concept. Emotional and rational components like the desire for stability and order are just as important here as references to specific spaces with topographic peculiarities (landscape, nature) as unique social and cultural forms. The former are not necessarily conservative by nature or in conflict with change and modernization, but may simply express the wish to actively play a role in shaping these changes rather than being a passive subject.

The German word Heimat is written in different ways in Middle German, Old German and Middle Low German sources[13] The root meaning roughly corresponds to “ancestral seat.” It is directly related to the word heim or “home,” referring to a house or place of residence. It likewise denotes a legal status and is linked to the term Heimatrecht (right of domicile), referring to rights of residency acquired by birth, residence or marriage and including the obligation to contribute to the common weal.[14] The term Heimweh (homesickness) has been used to describe an affliction since the late seventeenth century, in particular as a malady affecting Swiss mercenaries.[15] The term was included in Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie under the heading hemvé and was not restricted here to the Swiss.[16] Thus, the notion of homeland was addressed in the Francophone world as well.

In German-language reference works, the lemma Heimath appeared, for example, in 1781 in Krünitz’s Oekonomische Encyklopädie, defined as the “place, country where someone is at home [daheim], i.e., his place of birth, his fatherland.”[17] Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm’s Deutsches Wörterbuch gives a basic definition of Heimat as “the land or region [landstrich] in which one is born or has permanent residency.”[18] German-language “conversation encyclopedias,” whether the Brockhaus Enzyklopädie or the Meyers Konversationslexikon, contained the lemma since their very first editions, with little variation in its basic meaning, emphasizing in particular the legal concept – perhaps an indication of how controversial it was beyond these semantic and legal aspects.[19] Contemporary German-language encyclopedias are less reserved, broadly depicting changes in meaning as well as pointing out conflicting concepts. A recent edition of Brockhaus offers the following basic definition, however: “a partly imagined, partly specifiable area (country, region or place) with an immediate familiarity that is constitutive for one’s respective identity by virtue of one’s hailing from there or due to comparable ‘primal’ feelings of affinity.”[20]

In general, encyclopedia editors were partial to textual sources of a (highly) literary, legal or religious provenience. Belletristic literature reflected the concept’s increasingly controversial nature and hence its expansion as of the eighteenth century.[21] The prefixes “Heimat-” (in nouns) and “heimat-” (in adjectives and adverbs) were common, often as a qualifiers of topographic terms: Heimatland (homeland), Heimathaus (the house one makes his home in), Heimatgewässer (native waters), or to describe states of mind and being: heimatsüchtig (homesick), heimatlos (homeless), etc. Ever since the Enlightenment, in other words, Heimat and its meaning for individuals and groups was a source of reflection in the German-speaking world – and elsewhere – and this with increasing reference to individual processes of identification with regard to spaces, values, social and cultural norms, etc. with a particular emphasis on its emotional aspects. This gave rise to a broader debate on Heimat as a fundamental concept describing the relationship between the individual and his immediate, lived-in sociocultural environment in light of the existence of large social entities and abstract claims to loyalty. Heimat was viewed, so to speak, as yet another basic agent of group formation alongside the family. Deliberations ranged between an “open” and “closed” concept of Heimat – open in the sense of transformation, adaptation, assimilation of “foreign” impulses; closed in the sense of a sociocultural space whose basic substance is not to be altered if possible and whose development should largely occur autonomously.[22] What all of these positions share is that Heimat, though not always existing a priori, is nonetheless a constant point of reference. Alon Confino demonstrated this quite succinctly for the period after 1918 using statements made by Kaiser Wilhelm II, Ernst Jünger and Kurt Tucholsky: “the idea of Heimat was one thing they shared as Germans.”[23]

This brief intellectual history of the term makes clear that Heimat evolved into a key concept over the course of two centuries, one attempting to account for locally based identity processes at an individual level in their relation to larger social and political units. It focuses on the positioning of the individual in complex relationships, spatially circumscribed to begin with, but allowing linkages well beyond the individual’s own world of experience. Philosophically and theologically, this can even extend beyond the here and now to transcendental communities. It is also apparent that the word has become a prolific generator of associations,[24] stimulating a wide array of disciplines in equal measure. In medicine and psychology, anthropology and sociology, in political science, philosophy, literary studies and historiography to name but a few, investigations on the concept of Heimat have generated an almost impenetrable tangle of observations, definitions and theories – not to mention its political instrumentalization. A number of key political-ideological concepts of Heimat will be discussed here in the section on historical research.

The many deliberations on the German term cannot be discussed exhaustively in this context. Instead, the phenomenon of Heimat will be investigated with a focus on the humanities and contemporary history with regard to two particular aspects. First is the question of the phenomenon itself. The geographical location of a person’s living environment is fundamentally defined as having certain boundaries, but may only play a minor role if a community sees itself as being bound to certain convictions and/or ideologies, especially in the form of religious faith (the true home of a Christian, according to theological doctrine, being found in the world to come[25]). In this case Heimat stands for a transcendental value and reference point, which the individual nevertheless always links to a certain community. This is how philosophy has approached the word Heimat. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, for example, located Heimat in the realm of the spirit.[26] Karl Marx was preoccupied with conditions of production and alienation, and so it was perhaps no accident that he seldom used the word Heimat, proclaiming with Friedrich Engels in their Communist Manifesto that workers had no fatherland.[27] The workers’ movement and their political conviction would be the proletariat’s homeland, one that required no spatial ties. And according to Ernst Bloch (1885–1977), to cite a more recent example, homeland is a potential utopia, “something that shines into everyone’s childhood and where no one has ever been.”[28] Heimat in this case acquires a mythical component. It is obvious that the phenomenon itself, homeland, is hardly limited to the German-speaking world, and yet the German word Heimat has its own specific meanings and has been the subject of continual discussion for more than two centuries.

The phenomenon has been addressed both explicitly and implicitly by philosophy and the social sciences as well as by anthropology and ethnology, whereas literary studies[29] and especially historiography are interested in its temporal, spatial and culture-specific manifestations. This brings us to the second aspect, its denoting the specific manifestations of this concept of identity. These do not always fall under the label of Heimat, but sometimes concern the development of regional or local identities and forms of nation-building. They are found in transnational and global-history, including works on migrant groups and their relationship to receiving societies as well as on minorities in nation-states. Historical investigations explicitly concerned with Heimat (or the lack thereof – the experience of exile and forced migration[30]) naturally restrict themselves to the German-speaking world, namely: Imperial Germany, the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany, the Federal Republic, the German Democratic Republic and post-reunification Germany. Apart from reflections of a philosophical or sociological nature, these studies have heavily relied on various widely accepted anthropological and ethnological lines of thought.

Theoretical Approaches

Before taking a closer look at these anthropological and ethnological approaches, we should orient ourselves in the maze of theory. The term Heimat has been used throughout the German-speaking world in literature, medicine and philosophy ever since the eighteenth century, though seldom has the actual phenomenon been explored in much detail. Literature, especially the romantic poets, frequently referenced the motif of loving, losing or longing for one’s homeland.[31] This was a parallel development to the “discovery” or revaluation of local culture by Enlightenment thinkers the likes of Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803), who posited a meaningful relationship between human beings and their place of birth. Added to this were geographical considerations, which likewise claimed that basic local living conditions had a formative influence on the character of the people living there. Geographer Carl Ritter wrote in 1806 that “locality has a decisive influence on all three realms of nature […], on the extraction of natural products, their processing and distribution, as well as on the physical build and the emotional predisposition of people, on their possible or actual unification as peoples, states […].”[32]

Though Ritter was thinking in larger categories when he talked about “locality,” his approach was still very useful for imagining the local on a much smaller scale. All of these ideas were unfolding in the face of socio-economic transformation and emerging concepts of nation that conceived of state order not as a (pure) political construct but as an organization that belonged together naturally, as it were. This gave rise to a controversy over the characteristic features of local “cultures” and overarching structures, which due to their shared, “elemental” (urwüchsig) features were thought to form natural units. Later, the term “cultural nation” gained currency. These kinds of debates were not limited to the German-speaking world but were found across Europe if not beyond.

Cultural anthropologists variously refer to the sociological approaches of Georg Simmel (1858–1918), Wilhelm Brepohl (1893–1975) and René König (1906–92) among others. German sociology of the 1950s and 1960s in particular was responding to the social problem of massive forced migrations caused by Nazism and its aftermath. In sociology, too, Heimat has been understood as a web of relationships in a specific space that is experienced subjectively.[33] In the modern period these relationships have been marked by assimilation and transformation, in “old societies,” however, it was thought of as being stable.[34] The community, for René König, was the seat of emotional bonding and the sense of security that people feel in a specific social, economic and cultural fabric. This bond is all the stronger, the longer a person resides there, and finds expression in symbolic identification, a part being representative of the whole (pars pro toto).[35] Sociologists are still developing notions of Heimat with the underlying assumption that Heimat is a concept of identity that is essential for the integration of human beings in their day-to-day social context. References to values, traditions and communal experience remain important points of reference for a sociological approach to the concept. As in anthropology, however, the concept is neither restricted to the German-speaking world nor to a static frame of reference.

Anthropological Approaches

Anthropological approaches are the most importance point of reference in the historiographical debate on Heimat. The works of Hermann Bausinger and Ina-Maria Greverus have acted as an important stimulus for historians and cultural historians in recent decades. Both have in common an intense investigation of the conceptual history of Heimat – in Bausinger’s case mainly spanning the nineteenth and twentieth centuries,[36] whereas Greverus reaches somewhat further back and bases her literary-anthropological work on a wealth of source materials.[37] Like Greverus, Bausinger made repeated attempts to define the term. One of the most frequently quoted is this one: “Heimat as a near-world, a familiar one that is comprehensible and predictable, as a framework in which behavioral expectations are stabilized, in which meaningful, foreseeable action is possible – Heimat, in other words, as a contrast to foreignness and estrangement, as a realm of appropriation, active penetration, reliability.”[38] Another catchphrase coined by Bausinger refers to Heimat as a “place of compensation,” that is to say as a place of refuge from change and the loss of meaning, a place to counteract insecurities.[39] And yet Heimat, for Bausinger, is not something that simply exists; it demands “active appropriation,” which also means being aware of the historic dimensions of Heimat, understanding them as “something that is formed” (etwas Gewordenes).[40] Heimat, at any rate, is a reference value linked to basic needs as well to desires and expectations of the present and the future. This is what allows the concept of Heimat to be harnessed for political and ideological purposes. Bausinger makes a case for conceiving of Heimat as a “nexus of life, an element of active engagement that does not stop at external symbols and emblems,” and says it should not be reduced to a certain usage or instances of ideological instrumentalization.[41] Ina-Maria Greverus is more insistent in tracing the phenomenon back to anthropological constants that she describes with the concept of “territoriality.”[42] This refers to the necessary connection between an individual and a place that satisfies his needs for stimulation, security and identity, and enables “behavioral security,”[43] the individual being able to experience himself “as a recognized and recognizing member of a socio-culturally structured space.”[44] The attachment to a territory or the desire for one is not an indissoluble link to a certain geographic space; what underlies this concept is the idea of a territory.[45] This territory, according to Greverus, can be understood as a “space of satisfaction,” as the socio-cultural space in which individuals experience subjective-emotional security, identity and the freedom to act.

Greverus conducted a detailed investigation of territoriality using the example of Heimat in the German-speaking world. And she emphasized time and again that, although the word Heimat is indeed peculiar to the German-speaking world, the principles of territoriality and space of satisfaction are anthropological constants founds in every form of human society.[46] An essential part of this concept is that territorial behavior and Heimat are culturally determined.[47] The forms of expression they take are therefore always embedded in specific historical contexts.

Hence the term Heimat, according to Greverus, is both a technical term (homeland) describing a particular phenomenon (territoriality) independent of language as well as a specifically German term (Heimat) found in everyday and elevated speech whose content is historically conditioned and which has certain, culturally determined connotations. The spatial parameters and emotional charge of Heimat evident since the nineteenth century are proof of its cultural determination. They indicate that the debate about Heimat is a reaction to actual or supposed processes of modernization, to the planning and formation of nation-states with all of their attendant social changes, as well as to increased mobility. Philosophical and theological considerations which endeavor to give the term a transcendental slant are evidence of the same tendency.[48] Self-reflection about territoriality and spaces of satisfaction usually occurs when these appear to be threatened or challenged. It is these debates about Heimat that make the phenomenon relevant to historians.

Heimat as a Field of Historical Research

An overview of historical research on the topic of Heimat reveals several other areas of focus: first, the German Empire and its politics of identity (with regard to its colonies, too); second, the radicalization of the Heimat discourse in the German Empire, the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany; third, the Heimat discourse of the 1950s and 1960s and to some extent the changing discourse since the 1980s. The term Heimat is nothing new to historians. The systematic documentation of local customs, traditions, poetry and culture starting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was done from a historical point of view. Heimat likewise cropped up in German academic historiography in discussions about local identities. Investigations of völkisch-nationalist movements or natural and environmental history also refer to the relevant activities of heritage societies (Heimatvereine) and homeland associations (Heimatverbände) in the German-speaking world. It was only relatively late, however that the phenomenon of Heimat became an independent topic of historical research.

German Empire, Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany

In the United States, both Celia Applegate and Alon Confino provided important impulses in the 1990s, integrating the nineteenth- and twentieth-century discourses on “Heimat” into their deliberations on German national identity since the imperial era.[49] Both developed their theories on the basis of regional examples, Applegate using the Palatinate and Confino Württemberg. In both cases the concept was interpreted as trying to integrate the respective region into the newly founded German state of 1871 by redirecting feelings of regional loyalty towards the German nation. This of course implied either awakening these feelings in the first place or strengthening and channeling them in the right direction. The advocates of this movement, according to Applegate and Confino, were liberal to liberal-conservative middle-class circles and local notables.[50] The concept of Heimat enabled viewing regional particularities and characteristics as variants of an overarching whole, thus resolving or weakening conflicts of loyalty between region and nation. Both investigations concern themselves with the conceptual history as well as the political and ideological instrumentalization of Heimat. They point to the concept’s usage by heritage societies, local history museums and historians, as well as by local and regional festivals. Behind the specific idea of a Heimat-related identity, writes Confino, lurked something entirely different, however, namely invention, myth, nostalgia and sentimentality.[51] “Heimat […] became the ultimate metaphor in German society for roots, for feeling at home wherever Heimat was.”[52] Wherever there was Heimat, there was nation – for a range of protagonists, despite their many recognizable differences. Confino embeds his deliberations in the literature on collective memories (following Maurice Halbwachs). Accordingly, the idea of the (German) nation was to be understood as a process of collective negotiating as well as the exchange of memories, whether in the form of the written word, images or cultural practices.[53] The works of both Applegate and Confino show how the Heimat movement adapted itself to the times, harking back to traditions of the nineteenth century in the Weimar Republic and Nazi Germany after the demise of the German Empire but adjusting to the given circumstances, and sometimes – in the Nazi era – serving political-ideological purposes.

A conspicuous development in the German Empire was that a range of institutions committed to cultivating the ideals of Heimat were increasingly drawn to conservative, nationalist, chauvinist and racist ideas. This was manifest in national umbrella organizations such as the Dürerbund (Dürer League, founded in 1902 in Dresden) and the Bund Deutscher Heimatschutz[54] (German League for the Protection of the Homeland, founded in 1904, likewise in Dresden). Both aimed at the preservation and protection of the locally specific that was nonetheless considered German – in the arts, culture or nature. Fundamentally critical of or even hostile towards modernity and industrial society, they saw the rootedness of people in a landscape as an antidote: Heimat as “a corrective [Ausgleich] through the satisfaction of physical and emotional needs,” as Ferdinand Avenarius, cofounder of the Dürerbund, put it in 1904.[55] It was a matter of “feeling homelands around us” as opposed to “violated nature,”[56] by which he meant changes to the soil, water and woodlands caused by economic interests. This was accompanied by a certain defensiveness towards everything “foreign” (fremd) and the idealization of an organic connection between landscape, nature and “ethnicity” (Volkstum). The focus of the Heimatschutz movement and early nature preservation was always the “landscape,” more specifically the German Landschaft, construed as being unmistakably formed by the respective “tribally” (stammlich) distinctive Landsmannschaften or territorial associations.[57] There were thus countless points of contact here to völkisch ideology. Heimat could be linked to the people born and ancestrally rooted there, and thus served as the foundation of the “blood and soil” ideology emerging in the 1920s. This manifestation of the Heimat discourse and its linkage to increasingly radicalized nationalist movements that pinned their hopes on an ethnically and culturally homogeneous population has been adequately explored by historians such as Hans-Ulrich Wehler in his concise and exemplary study of the Deutscher Ostmarkverein (German Eastern Marches Society).[58]

The motif combines images belonging to the standard repertoire of Heimat iconography: a village, rural surroundings, church steeple and peasants. Dark clouds symbolize threat, the rainbow hope.

Poster: “War bond: In defiance of the enemy / For the protection of the homeland,” ca. 1916, artist: Wilhelm Schulz (*1865), Verlag Oskar Leiner (Leipzig), 23 x 33.5 cm. Source: Bundesarchiv Plak 001-005-060-T2 courtesy of the German Federal Archives

And yet only part of the Heimat movement (or Heimat discourse) has been focused on in the process, the one supplying nationalist or chauvinist movements with locally based arguments. The Heimat movement of the Weimar Republic has also been viewed in this manner. It was “fundamentally politicized,”[59] according to Willi Oberkrome, with a conservative and sometimes rightwing-radical veneer. Its influence was largely thanks to the subject of Heimatkunde (local history) being anchored in school curricula and hence a part of civic education, albeit in a more innocuous form. A key representative of the conservative Heimat movement, the educator Eduard Spranger, emphasized that Heimat was something that had to be acquired: “The notion is completely false that you are born into a homeland [Heimat]. A given birthplace only becomes a homeland once you have lived your way into it. This is why it is possible to create a homeland for yourself far away from the place you were born.”[60] But the Heimat discourse of the 1920s had a modern wing as well, open to urbanization and industrialization provided that new infrastructure and production sites be integrated into the landscape and, if possible, constructed with local building materials.[61]

The authorities in Nazi Germany aimed to centralize the Heimat movement, “bringing it into line” – the so-called process of Gleichschaltung – and transforming it according to the prevailing ideological norms. While it is true that the word Heimat may have been eminently suited to arguing the Nazi line, the concept as understood by the organized Heimat movement was not the same as the Nazi Party’s. The Heimat movement was based on a federalist, local principle,[62] whereas Nazi ideology was founded on the notion of an overarching, ethnically homogeneous “national community” or Volksgemeinschaft.[63] They did, however, agree on the principle that only the love of one’s homeland enabled the love of one’s fatherland. The value of Heimat and region was elevated accordingly, since these were thought to contain important elements of a shared national or popular culture peculiar to an imagined community.[64] Though the culturally conservative, nationalist and occasionally racist outlook of existing societies and associations offered points of contact to the new authorities, the Eigensinn (self-will) of the Heimat movement was not so easy to neutralize or reshape. Leading figures in the heritage societies and homeland associations may have curried favor with the regime and been confirmed Nazis, but they always retained a certain scope of maneuver, which after 1945 could be interpreted as a sign of having kept away from politics and ideology.

Moreover, there was no uniform strategy on the part of the Nazi Party of how to deal with these mostly bourgeois societies and associations. Added to this was the competition between different organizations, typical of the Nazi period. Alfred Rosenberg’s “Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur” (Militant League for German Culture) was competing with the “Reichsbund Volkstum und Heimat” (Reich Federation of Folkdom and Homeland), led by Werner Georg Haverbeck. This situation gave the Heimat movement a certain latitude, since the Nazi umbrella organizations were not always able to penetrate the existing groups and bring them into line ideologically. Separate initiatives also developed in individual administrative districts, or Gauen. In Saxony, for example, Gauleiter Martin Mutschmann founded the Heimatwerk Sachsen (Homeland Organization of Saxony) in 1936 which aimed to centralize all regional cultural efforts. But here, too, it became apparent that “the traditional forces of the Heimat movement had increasing opportunities to use the newly created structures of the ‘Heimatwerk’ for asserting their own interests.”[65] Though hardly a locus of resistance, the Heimat movement does reveal the limits of Nazification, pointing to forces of inertia at the local and regional levels vis-à-vis Nazi organizations and attempted cooptation. With the collapse of Nazi Germany in 1945, the Heimat movements were remarkably quick to localize their structures once again.[66]

Heimat after 1945

The 1950s and 1960s have received the most attention from scholars in more recent contemporary history. The early years of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) were marked by massive population shifts caused by flight and expulsion. About 12 to 14 million ethnic Germans were forced to leave their places of residence and start a new life elsewhere. Locals had to deal with new-arrivals, and everyone had to come to terms with the changes in their living environment. Thus, Heimat figured prominently in postwar social discourses. The so-called Heimatvertriebene, ethnic Germans expelled from their former homeland, sought a place in their respective postwar societies in Germany East and West, some of them hoping to one day return to territories lost in the war. The established population was faced with the task of dealing with a new situation and possibly reinventing their own identity. Alongside existing and newly formed local (cultural) organizations came the ones established by migrants after the end of the war.

The “Block der Heimatvertriebenen und Entrechteten” (Bloc of Expellees and Disenfranchised, BHE), founded initially in Schleswig-Holstein in January 1950 by Waldemar Kraft (1898–1977), was a political lobby group in the Federal Republic working at the regional and federal level to facilitate integration in West Germany and give political representation to expellees, defending their right to return.[67] The BHE was active in regional and federal governments in the 1950s before eventually losing its influence. While the BHE attracted the attention of scholars early on, expellee societies and associations or institutions taking up their cause at the regional and local level were only addressed much later.[68] Landsmannschaften and other societies based on territorial association[69] or the shared experience of (forced) migration were founded immediately after the war, many of which are still in existence today.

Though the narrative of the rapid and successful integration of refugees and expellees fostered by the politics of the 1950s and 1960s has recently been the subject of scrutiny,[70] two things have yet to be explored in detail: the socio-cultural experience of new-arrivals and the processes of identification (or lack thereof) with their new local and regional environments.[71] The local heritage societies and homeland associations they encountered there drew on their pre-1933 activities while simultaneously downplaying their implication in Nazism, if they even addressed it at all. How both migrants and locals coped with this situation still needs to be investigated in more detail.[72] Whatever the case, a marked interest in Heimat in the first two decades after the war seemed to offer a means of coping with the experience of being uprooted. The “production of meaning by means of homeland-cultural organizations and historical policymaking in the long postwar period into the 1960s offered an extensive sphere of integration,” writes Habbo Knoch.[73] This sphere of integration encompassed not only newcomers but also established residents. The wealth of sociological research[74] dedicated to the topics of homeland, foreignness, refugees and expellees from a theoretical as well as an empirical perspective[75] would be a useful resource for future historians in this field.

“Socialist Heimat” in the GDR

The debate on Heimat in the GDR was different than in the Federal Republic. The government in East Berlin initially rejected the concept of Heimat as the haven of an ineradicable and romanticizing petty bourgeoisie.[76] Yet regional cultural associations could not simply be integrated into socialist mass organizations and aligned with the more politically desirable notion of internationalism. Instead, a socialist concept of Heimat was invented, underscoring the role of the individual in the collective and his responsibility to the world around him. Heimat was now no longer the preserve of the bourgeoisie but belonged to the workers, who shaped their environment collectively according to the principles of socialism, thus ensuring the rootedness of these principles.[77] Attachment to one’s socialist homeland was to prevent mass flight to the West, while also shielding against (cultural) influences from the capitalist world in general.[78] In essence it boiled down to the attempt to give the word a positive connotation while warding off negative influences from the past and the West (i.e., West Germany) such as the preservation of existing local and regional traditions.

The SED in Thuringia, East Germany, canvasses votes with a photographic image that could have just as well been used on movie posters for a West German Heimatfilm. A young woman in what appears to be traditional costume sits on a wooden fence before a sun-drenched valley free of modern influences. The poster reveals that older (bourgeois) notions of Heimat were still commonplace in the GDR. Only with the advent of a “socialist Heimat” in the 1950s did an alternative program emerge.

SED election poster: “For peace, justice and homeland,” SED state executive committee of Thuringia, September/October 1946 ca. 42 x 58 cm. Source: Bundesarchiv Plak 100-015-038 courtesy of the German Federal Archives

The focus of local identity-building was to be the overall socialist state[79] and the notion of internationalism. It was also necessary to overcome bourgeois-capitalist property relations, since these were thought to ultimately lead to an instrumentalization of Heimat. All of this was thought to contrast the approach to Heimat in the Federal Republic.[80] The official representative of the concept of a socialist homeland was the Kulturbund (Cultural League). Founded in 1945, it only had a limited say, however, in the agenda of its affiliated associations and hence had little influence on their practical work and activities. Thus, a varied network of regional and local cultural associations developed alongside organizations that were more or less free to pursue their activities, depending on political directives from Berlin and provided they did not engage in direct opposition to the regime. Thomas Schaarschmidt concludes that “nothing facilitated the integration of society into the political system as much as the toleration, usually for tactical reasons, of free social spaces in opposition to the system.”[81] In this sense, local and regional cultural organizations were an important factor in stabilizing the system.

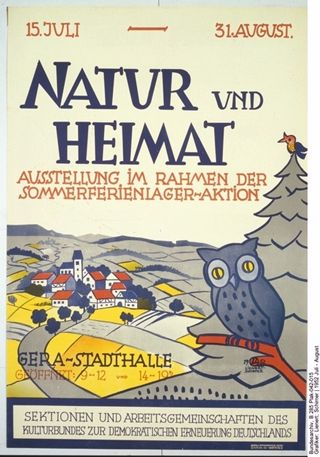

A small village in the midst of a slightly hilly, agricultural landscape with small-scale farms. The owl and pine tree suggest a forest. There is no room for modernity in this picture – even in 1952 the iconographic models of the Heimatschutz movement from the imperial era are invoked in the GDR.

Exhibition poster: “Nature and Homeland,” Gera 1952, exhibition in the context of a summer-camp drive of the Kulturbund. Artists: Lienert and Schirner, Printed by: Gerth & Oppenrieder, Gera. Source: Bundesarchiv B 285 Plak-042-015 courtesy of the German Federal Archives

“Heimatfilm” and Heimat iconography

The hugely successful West German Heimatfilm of the 1950s and 1960s has been given special attention in cultural-historical research.[82] Initially decried as shallow entertainment, the success of this genre – originally a product of the late 1920s – seemed, at first, to be due to a widespread desire for escapism. More recent investigations offer a somewhat more nuanced picture. The Heimatfilm addressed fundamental social issues in its own specific way, whether modernization, displacement and migration or the urban-rural divide. It used the imagery of familiar Heimat iconography to convey impressions of a stable order that appealed to aesthetic sensibilities and was capable of holding its own in the modern era. Though the notion of Heimat used here clearly recalls the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and hence carries conservative connotations, the Heimat of the Heimatfilm was not divorced from current events, but integrated despite its conservative bent elements of modernity, mobility and technology in the spirit of reconciliation (as understood back then). The Heimatfilm was not just a West German phenomenon but was found in Austria and the GDR as well. In the latter case, however, it was linked to a certain conformity with the prevailing political system and a “progressive” socialist, indeed quite nationalist message.[83]

While it is true that the importance visual communication has repeatedly been pointed out with regard to the concept of Heimat,[84] by Alon Confino in particular (“We should think of national memory also as an iconographic process”[85]), and, not surprisingly, with regard to the Heimatfilm, the topic has yet to be addressed in great detail. And yet there is no denying that the discovery of local surroundings, landscapes, architecture and nature in their specific meaning to individuals is an important step towards establishing a local identity. Confino emphasizes that the images used were interchangeable in terms of their form, aesthetic and motifs, and could hence be regarded as universal signs and symbols representing the notion of Heimat.[86] At an individual level, however, it does make a difference whether it’s your own locality represented in an image or another one far away. Generally speaking, the of visualization of one’s own living environment is understood as an attempt to portray this world as being equally valid – in regional, national or global comparison.

This can be viewed as an outgrowth of the Heimatkunst movement that emerged in late Imperial Germany. Regarded by art historians as conservative and traditional and scarcely acknowledged by conventional historians, being mentioned in passing at best, the movement was in fact considerably more complex, as Jennifer Jenkins points out. The turn to local and comparatively undramatic motifs – “unworthy” subject matter from the point of view of the academy – was at once traditional and highly modern: “The local environment was the terrain upon which new visual languages were thought out.”[87] The movement, moreover, was hardly limited to Germany but was found throughout Europe and elsewhere. With a view to everyday aesthetic practices it is immediately evident that, for example, the amateur-photography movement which emerged in industrialized nations at the turn of the twentieth century had a distinctly local orientation but was also part of an international network and quite capable of promoting its “visual agenda.”[88] This, in turn, had an impact on the applied arts. Elizabeth Edwards sees the English amateur-photography movement, which as of the 1880s was more or less systematically producing local and regional images, as “entangled with the tension between local and national desires and imagination, between the local negotiation of dominant structures and the translation of the local within a visual discourse of the national.”[89] The postcard aesthetic still ubiquitous nowadays is rooted in this very movement.

Differentiations and the Rediscovery of Heimat after 1970

The literature shows that the 1970s inaugurated a new phase in the history of Heimat. In Axel Goodbody’s diagnosis, “Heimat was redefined and regional identities were rehabilitated in the context of the environmental movement of the 1970s.”[90] Ina-Maria Greverus, herself a contemporary witness, locates this rehabilitation of the term in the new civil-society protest movement, which resulted in its political appropriation and a boom in scholarly interest reflected in “the preservation of historical monuments, urban and village renewal, a new historical consciousness, old-town festivals, anniversaries, nostalgia, dialect, folk songs, cultural-historical museums” as well as in advertising and public relations.[91] The Heimat boom in a museum context that emerged in the 1970s[92] is an offshoot of this, despite the fact that museums of local history – the Heimatmuseum – had existed long before. The anti-nuclear-power movement, discussions of identity in the 1980s, the debate on globalization[93] as well as German unification all relied at some point or another on the concepts of Heimat and regionalism or local identity politics, regardless of whether this happened in a rural or urban setting. Historians of the nature conservation and environmental movements have traced these back to the Heimat movement of the German Empire and discovered numerous continuities.[94] The protection of nature and concerns about the environment usually went hand in hand with a commitment to one’s immediate surroundings, since building up the necessary support required knowledge of the local situation, its social and cultural realities.

Heimat Overseas

One specialized field of recent historical research is colonial history. Prompted partly by the cultural turn and partly by post-colonial studies, this new field of scholarship has reexamined the question of the self-understanding of colonizers. Migration history and global history have also acted as catalysts more generally.

During the German Empire, colonizers and colonial societies endeavored to integrate the colonies into a national narrative. This was done with the help of the contemporary discourse on Heimat. Krista O’Donnell has argued, for example, that the principle of Heimat was directly transferred to the colonial project. German settlers were viewed as a Heimat-creating community, who fashioned their living environments according to the very same principles that held in the German Empire, applying themselves to productive work with a sense of rootedness and emotional attachment, and defining themselves against the “other.” A core aspect of this concept of Heimat was their sense of belonging to a nation: “The ideal of Heimat, with all its domestic connotations, is particularly important in the German case because of its centrality to popular conceptions of German nationalism.”[95] Only when they had succeeded in creating a Heimat in the colonies by building up a community of settlers was a colony – that is to say, its German element and not the indigenous population – considered equal in value to other parts of the German Empire.

The illustrated magazine Kolonie und Heimat (Colony and Homeland) was the official publication of the Women’s League of the German Colonial Society. Its aim was to popularize the colonies in Germany and make them attractive as settlement areas. The African woman in a wicker chair and European reform clothing stands in contrast to the image on the magazine she’s holding in her hands, but suggests the possibility of Heimat in the colonies. The picture must have been disconcerting at the time, since Heimat was hardly associated with people living in the colonies, much less with African women displaying a dignified and sophisticated middle-class domesticity.

Kolonie und Heimat ca. 1911, b/w photograph 18 x 18 cm. The woman’s identity and the photographer are unknown. Source: Bundesarchiv Bild 146-2014-0007 courtesy of the German Federal Archives

This of course disregarded the possibility that identification with and loyalty to the “new Heimat” could lead to political detachment from the motherland. The same applied to colonial enthusiasts after 1918, who imagined a better Germany, as it were, in the former German colonies. As Willeke Sandler observed in the case of photographer Ilse Steinhoff, there were efforts to capture in photographic images how German settlers in the 1930s succeeded in preserving their “Heimat.”[96] This was a variation on the theme of Heimat as a “place of compensation” (Hermann Bausinger). German settlers were held up as shining examples of a “healthy” relationship between nature, their own environment and humanity, viewing the colonial community as a way to regenerate German society and an integral part of this selfsame society.[97] Sandler’s study is also remarkable for addressing the connection between gender and Heimat – a hitherto neglected field of research.

Perspectives

Investigations into the phenomenon of Heimat seldom extend beyond German borders. Even Austria and Switzerland are given short shrift, whereas transnational approaches are lacking entirely with the exception of colonial history. The visual history of Heimat has likewise received scant attention from scholars. A divergent leftist or liberal concept of Heimat and a focus on gender-specific issues are marginal features in the historical literature.

The German notion of Heimat is perceived as a uniquely German phenomenon, distinctly different from other concepts of homeland throughout the world. With the exception of nature conservation and environmental protection,[98] there are no comparisons to analogous movements in other cultures. Thus, the literature on the German-speaking world sticks to the German concept of Heimat and only concerns itself with the broader phenomenon when linked to a discourse on homeland. This explains why organizations that prominently feature the word Heimat in their names or agendas are being given particular attention. There is general agreement that conservative-chauvinist and racist parts of the Heimat movement should not be underestimated.[99] Will Cremer and Ansgar Klein emphasized this conservative element as early as 1990, pointing out its “knee-jerk traditionalism,”[100] its inherently chauvinist elements and völkisch thinking.[101] It should be noted, however, that the aforementioned situation is largely the result of gaps in research. To date, there has neither been an investigation of these writings and institutions with respect to their actual political leanings and hence the range of this discourse, nor have there been sufficient studies on the Heimat discourse of the 1920s and 1930s. There is also a dearth of studies on the history of everyday life focusing on the urban, local and regional forms of liberal Heimat movements and their impact, previous research having centered on the antimodern and chauvinist varieties. More recent analyses from a conceptual-history perspective show that there were multiple concepts of Heimat in the nineteenth century, ranging from more “open” ones that viewed Heimat as something dynamic and not necessarily restrictive to “closed” ones that conceived of it as something to be protected from foreign influences.[102] The dynamics and elasticity of the term is particularly striking in descriptions of diaspora communities, which lend expression in a local context to roots, loyalties and a sense of belonging as well as to emotional attachments and social ascriptions. In this respect, from an overseas perspective the entire nation-state is Heimat.[103] A different picture emerges, however, when viewed from within the diaspora community. From this vantage point Heimat can mean one’s current environment, one’s original local Heimat prior to emigration, or even the entire country of origin. These distinctions need to be given more attention. Diverse ties to Heimat are important even within a given region. What role did it play for a subnational, political or administrative body such as a federal state in the German Empire? Was there any resistance to it? What happens when a local Heimat discourse does not address its integration in the nation or federal state, rejects cooptation, and tries to evade political instrumentalization?

These aspects need to be analyzed more fully. On the one hand, we need to look beyond the German word Heimat and inquire into the larger phenomenon of homeland as an anthropological concept. On the other, the Heimat discourse needs to be differentiated with regard to its deviations from the norm. As mentioned above, a leftist discussion of Heimat has existed since the nineteenth century. Its points of reference need to be examined as well, such as the relationship between Heimat and region (independent of any state borders running through them). The relationship between locality and globality also needs to be explored more intensely. Conflicting concepts of Heimat can thus be read “against the grain.” Do all concepts of Heimat need a local connection or was the term simply used as a catchword for chauvinist-nationalist thinking? Do they need the fiction of an unchangeable folk culture and the timeless character traits of a local population, formed by nature and landscape?

The specific manifestation of the dominant Heimat discourse – for example, from the late German Empire to the Nazi period – looks different when taking into account liberal and leftist Heimat discourses. The later Nobel Peace Prize winner Alfred Hermann Fried, for example, wrote in a 1908 essay on patriotism that a sense of Heimat could help counteract excessive nationalism. He argued: “Our habituation to people, things and institutions, to the extent that these can be perceived by the senses, constitute the original and actual feeling of patriotism, our sense of homeland [Heimat].”[104] This sense of Heimat, he added, was the foundation for a well-reflected patriotism in the context of a constructive competition between nations. In Fried’s opinion, ties to one’s homeland – evidently even outside the German-speaking world – were an antidote to radical nationalism.

If Alfred Fried linked Heimat to “people, things and institutions,” the leftist discourse on Heimat was a concept devoid of place, striving for a socialist community regardless of where this community materialized: “Our homeland is the world: Ubi bene ibi patria – where life is good, i.e., where we can be human, that is our fatherland,” is how Wilhelm Liebknecht put it in 1871, contradicting, as it were, the Communist Manifesto.[105] The concept of a “socialist Heimat,” as developed in the GDR in the 1950s, is founded on this tradition. Heimat here was not primarily based on a nation or one’s place of birth, but remained quite narrowly focused on the appropriation and creative reorganization of one’s environment – in the spirit of socialism, of course.[106] On the other hand, the goal was a socialist fatherland within the international socialist community, a community that had no need for the conventional bourgeois-capitalist nation-state.

Another aspect worth investigating is a gender-history perspective. Thus, in 1843 Louise Otto elevated the emotional ties to one’s homeland, in particular those of women – “Heimat! How dear the word is, precisely to the female sex!” – into an argument for their right and duty to participate in the political process.[107] Demands for the increased commitment of women to the colonial cause were later justified using the argument that only with their assistance could colonies become something akin to a Heimat overseas, not only for racial and biopolitical reasons but with special emphasis on their cultural and emotional attachment, as described by the Frauenbund (Women’s League) of the Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft (German Colonial Society)[108] – incidentally a notion of woman's colonial duty that was found in Great Britain as well.[109] Female gender ascriptions or connotations played a special role in concepts of Heimat in the conservative discourse in general, as underscored by Peter Blickle: “male notions of the feminine are formative in the idea of Heimat.”[110]

It is important, furthermore, to link the Heimat discourse to globalization and relativize the nation as its privileged framework. Is Heimat transnational? From an anthropological approach in the sense of Greverus’s “territoriality” many phenomena subsumed under the concept of Heimat in the German-speaking world are actually an expression of modernization processes that are certainly not limited to this part of the world. The question is whether a specific emotional charge and an overemphasis on landscape are the distinguishing features of German Heimat as opposed to other local processes of identity-formation or whether there are other criteria at work. Heimat as an urban phenomenon has been the focus of recent discussion. Furthermore, local processes of identity-building in general are unimaginable without an emotional component and specific aesthetic references to space. The emotional appeal of having a homeland hardly appears to be the prerogative of the German-speaking world, as Rolf Petri pointed out in 2001.[111]

Conclusion

References to modernization processes, similarities to the development of nation-states, the refurbishment of local spaces and the back-to-nature movement all make abundantly clear that the concept of a homeland is by no means something specially German inherent to the concept of Heimat.[112] The word Heimat, of course, is specifically German.[113] But other societies as well seem to have their own territorial identity discourses, complete with emotionally charged references to certain landscapes or topographic-architectonic peculiarities. If our perspective is broadened to include global-historical reference points, the concept of territoriality / homeland can be used to better understand the underlying processes. There is an ongoing debate about whether nationalization and globalization, rather than being “two stages of a consecutive development,” are not in fact mutually reinforcing processes.[114] The relationship between globality and locality needs to be examined more closely. Locality, writes Angelika Epple, is a promising concept, because ultimately globalization is always embedded locally.[115] “What historians have to do is to show how the local is formed globally and, at the same time, how the global is put together locally.”[116] The cross-cutting category of territoriality / homeland links locality, regionality and globality to individual experiences. Unlike locality and regionality, Heimat could be understood here as a modern concept linking humans to their living environment and the world. There is no German “special path” in this case. The same applies to the relationship between homeland and nation. Only in the nexus of homeland / nation / world does the individual find his place in modernity. The insights and approaches of historical research on the German-speaking world and its concepts of Heimat can serve here as a model for analyzing such processes.

I would like to conclude by returning to the question posed at the very beginning of this essay as to whether Heimat is meaningful as a historical category. Locality, localism, regionality or territoriality would seem more neutral and transferrable. And yet there are arguments for using the German word Heimat outside its immediate context. At the linguistic level alone, the supposed untranslatability of the term should be taken with a grain of salt.[117] Locality and regionality would seem at first glance to have a stronger geographical connection and be more restrictive, locality representing the more narrow living environment of individuals (community) and regionality the immediate geographical and sometimes administrative framework. Neither requires an emotional component, which is indispensable to concepts of identity. Territoriality is the overarching category, whereas Heimat or Heimatism is a concept implemented in the modern era, expressing culturally formed and historically rooted manifestations of territoriality in the German-speaking world.

Translated from the German by David Burnett.

German Version: Jens Jäger, Heimat, Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 09.11.2017

Recommended Reading

Jens Jäger, Heimat (english version), Version: 1.0, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 13.8.2018, URL: http://docupedia.de/zg/Jaeger_heimat_v1_en_2018

Copyright (c) 2023 Clio-online e.V. und Autor, alle Rechte vorbehalten. Dieses Werk entstand im Rahmen des Clio-online Projekts „Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte“ und darf vervielfältigt und veröffentlicht werden, sofern die Einwilligung der Rechteinhaber vorliegt. Bitte kontaktieren Sie: <redaktion@docupedia.de>

References

- ↑ Joachim Wolschke-Bulmahn, “Heimatschutz,” in: Uwe Puschner/Walter Schmitz/Justus H. Ulbricht (eds.), Handbuch zur „Völkischen Bewegung“ 1871-1918, Munich et al. 1999, pp. 533-545.

- ↑ Bundesarchiv-Bildarchiv [Digital Picture Archives of the German Federal Archives], Plak 005 - Bundesrepublik Deutschland I (1949-1966), Plak 005-026-035.

- ↑ Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung [Press and Information Office of the Federal Government of Germany], Bundeskanzler Brandt, Regierungserklärung des zweiten Kabinetts Brandt/Scheel vom 18. Januar 1973, p. 56, online at http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/netzquelle/a88-06578.pdf.

- ↑ Ina-Maria Greverus, Auf der Suche nach Heimat, Munich 1979, p. 16.

- ↑ See the sole reference here, Johannes von Moltke, No Place Like Home: Locations of Heimat in German Cinema, Berkeley 2005 as well as the literature listed in footnote 82.

- ↑ Jan Palmowski, “Building an East German Nation: The Construction of a Socialist Heimat, 1945-1961,” in: Central European History 37 (2004), no. 3, p. 365-399. See also Thomas Schaarschmidt, “Regionalbewusstsein und Regionalkultur in Demokratie und Diktatur 1918-1961. Sächsische Heimatbewegung und Heimat-Propaganda in der Weimarer Republik, im Dritten Reich und in der SBZ/DDR,” in: Westfälische Forschungen 52 (2002), pp. 203-228.

- ↑ See Peter Blickle, Heimat: A Critical Theory of the German Idea of Homeland, Rochester 2002, pp. 2f.; Martina Haedrich, “‚Heimat denken‘ im Völkerrecht. Zu einem völkerrechtlichen Recht auf Heimat,” in: Edoardo Costadura/Klaus Ries (eds.), Heimat gestern und heute. Interdisziplinäre Perspektiven, Bielefeld 2016, pp. 51-76. Comparable terms are “homeland” in English, petite patrie in French, thuisland in Dutch, vlast in Czech, rodina (родина) in Russian, just to name a few examples.

- ↑ See Beate Mitzscherlich, „Heimat ist etwas, was ich mache“: eine psychologische Untersuchung zum individuellen Prozeß von Beheimatung, Pfaffenweiler 1997.

- ↑ Greverus, Auf der Suche, S. 28.

- ↑ Alon Confino, “On Localness and Nationhood,” in: German Historical Institute London Bulletin 23 (2001), no. 2, pp. 7-27, here pp. 15 und 26, online at http://www.perspectivia.net/publikationen/ghi-bulletin/2001-23-2/pdf.

- ↑ David Blackbourn/James Retallack (eds.), Localism, Landscape, and the Ambiguities of Place: German-Speaking Central Europe 1860-1930, Toronto 2007. Here, too, with reference only to German history as well as to the terms “locality” and “local studies.” Their study has close ties to global history studies at the local level or to studies linking the global and the local on the latter, see Angelika Epple, “New Global History and the Challenge of Subaltern Studies: Plea for a Global History from Below,” in: The Journal of Localitology 3 (2010), pp. 161-179.

- ↑ On the topic of conceptual history, see Kathrin Kollmeier, “Begriffsgeschichte und Historische Semantik, Version: 2.0,” in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, October 29, 2012, http://docupedia.de/zg/kollmeier_begriffsgeschichte_v2_de_2012.

- ↑ Etymologies of the word Heimat are legion. For more detail, see Andrea Bastian, Der Heimat-Begriff: eine begriffsgeschichtliche Untersuchung in verschiedenen Funktionsbereichen der deutschen Sprache, Tübingen 1995. Historical perspectives abound as well, e.g., Rolf Petri, “Deutsche Heimat 1850-1950,” in: Comparativ 11 (2001), no. 1, pp. 77–127, esp. pp. 83ff. An instructive literary perspective is offered by Blickle, Heimat; “Überlegungen zum Verhältnis von Heimat und ‚Spatial Turn‘: Friederike Eigler, Critical Approaches to Heimat and the ‚Spatial Turn,‘ ” in: New German Critique 39 (2012), pp. 27–48.

- ↑ It is sufficient here as an introduction to cite two in-depth encyclopedia entries from the nineteenth century, e.g., “Heimat,” in: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon. Eine Encyklopädie des allgemeinen Wissens, vol. 8, Leipzig/Vienna 1887, pp. 300–2, or Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, 6th ed., vol. 9. Leipzig 1907, pp. 82–3.

- ↑ Johannes Hofer, De nostalgia oder Heimwehe, Basel 1688, online at http://www.e-rara.ch/doi/10.3931/e-rara-18924; for more detail, see: Greverus, Auf der Suche, pp. 135–7.

- ↑ “Hemvé,” in: [Denis] Diderot, [Jean-Baptiste le Rond] d’Alembert, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 8, 1765, pp. 129–30. Heim-Weh is also given in-depth treatment in Johann Georg Krünitz, Oeconomische Encyclopädie oder allgemeines System der Land-, Haus- und Staats-Wirthschaft, vol. 22, Berlin 1781, pp. 773ff., online at http://www.kruenitz1.uni-trier.de/ [Sept. 2, 2016].

- ↑ Heimath, in: Krünitz, Oeconomische Encyclopädie, vol. 22, Berlin 1781, p. 796; online at http://www.kruenitz1.uni-trier.de/ [Sept. 2, 2016].

- ↑ Jacob und Wilhelm Grimm, Deutsches Wörterbuch, vol. 10, Leipzig 1935, p. 866, online at http://dwb.uni-trier.de/de/.

- ↑ “Heimat,” in: Meyers Konversationslexikon, vol. 8, Leipzig/Vienna 1887, p. 301; “Heimat,” in: Brockhaus Konversationslexikon, vol. 8, Leipzig/Vienna 1894, p. 970.

- ↑ “Heimat,” in: Brockhaus (online edition) 2012, https://uni-koeln.brockhaus.de/enzyklopaedie/heimat [Sept. 1, 2016]. Other encyclopedias are equally in-depth in their treatment of Heimat.

- ↑ For an introduction, see Gunther Gebhard/Oliver Geisler/Steffen Schröter, “Heimatdenken: Konjunkturen und Konturen. Statt einer Einleitung,” in: idem (eds.), Heimat. Konturen und Konjunkturen eines umstrittenen Konzepts, Bielefeld 2007, pp. 14–8, online at https://leseprobe.buch.de/images-adb/40/aa/40aab662-9431-4788-a5ca-d64c08388a3a.pdf. The Deutsches Wörterbuch makes references to Friedrich Schiller and Ludwig Uhland among others. The Goethe-Wörterbuch establishes the more emotional meanings in entries 2a and 2b of Heimat: Wörterbuchnetz, Trier Center for Digital Humanities, http://woerterbuchnetz.de/GWB/?sigle=GWB&mode=Vernetzung&lemid=JH02018#XJH02018.

- ↑ Gebhard/Geisler/Schröter, “Heimatdenken,” p. 22.

- ↑ Alon Confino, Germany as a Culture of Remembrance: Promises and Limits of Writing History, Chapel Hill, NC 2006, p. 55.

- ↑ Gebhard/Geisler/Schröter, “Heimatdenken,” p. 9. Friedemann Schmoll points out the term’s ambivalences: Friedemann Schmoll, “Orte und Zeiten, Innenwelten, Aussenwelten. Konjunkturen und Reprisen des Heimatlichen,” in: Costadura/Ries (eds.), Heimat gestern und heute, pp. 33–43.

- ↑ Hartmut Kress, “Heimat,” in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie, vol. 14, Berlin/New York 1986, p. 778.

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Vorlesungen über die Geschichte der Philosophie, edited by Karl Ludwig Michelet, Berlin 1833–36, pp. 172ff.

- ↑ Karl Marx/Friedrich Engels, Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei, London 1848, p. 14.

- ↑ Ernst Bloch, Das Prinzip Hoffnung [1954–1959], vol. 3, Frankfurt am Main 1985, pp. 1658.

- ↑ See, esp. Blickle, Heimat; Gebhard/Geisler/Schröter, Heimat; Elizabeth Boa/Rachel Palfreyman (eds.), Heimat: A German Dream: Regional Loyalties and National Identity in German Culture 1890–1990, New York 2000.

- ↑ There is a wealth of literature on both topics. For an introduction on exile see, e.g., Gregor Streim, “Konzeptionen von Heimat und Heimatlosigkeit in der deutschsprachigen Exilliteratur nach 1933,” in: Costadura/Ries (eds.), Heimat, pp. 219–41. On the problem of Heimat and forced migration, see the section “Heimat nach 1945.”

- ↑ Among more recent works, see, e.g., Blickle, Heimat; Gebhard/Geisler/Schröter, Heimat; Costadura/Ries, Heimat.

- ↑ Carl Ritter, “Einige Bemerkungen über den methodischen Unterricht in der Geographie,” in: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, Erziehungs- und Schulwesen 1806, vol. 2, p. 205. Ritter elaborates the same thought on pp. 210f.

- ↑ Wilhelm Brepohl, “Die Heimat als Beziehungsfeld. Entwurf einer soziologischen Theorie der Heimat,” in: Soziale Welt 4 (1952), pp. 12–22.

- ↑ Brepohl, “Die Heimat,” p. 16.

- ↑ René König, “Der Begriff der Heimat in den fortgeschrittenen Industriegesellschaften [1959],” in: Kurt Hammerich/Oliver König (eds.), Soziologische Studien zu Gruppe und Gemeinde, Wiesbaden 2006, pp. 357–62, here p. 359.

- ↑ See, e.g., Hermann Bausinger, “Heimat in einer offenen Gesellschaft. Begriffsgeschichte als Problemgeschichte [1986],” in: Will Cremer/Ansgar Klein (eds.), Heimat. Analysen, Themen, Perspektiven, vol. 1, Bielefeld 1990, pp. 76–90.

- ↑ Ina-Maria Greverus, Der territoriale Mensch. Ein literaturanthropologischer Versuch zum Heimatphänomen, Frankfurt a.M. 1972.

- ↑ Hermann Bausinger, “Heimat und Identität,” in: Konrad Köstlin/Hermann Bausinger (eds.), Heimat und Identität. Probleme regionaler Kultur, Kiel 1980, pp. 9–24, here p. 20.

- ↑ Bausinger, “Heimat und Identität,” p. 13.

- ↑ Bausinger, “Heimat in einer offenen Gesellschaft,” p. 89.

- ↑ Bausinger, “Heimat und Identität,” p. 21.

- ↑ Greverus, Der territoriale Mensch, p. 23.

- ↑ Gerverus, Der territoriale Mensch, p. 26; Greverus, Auf der Suche, p. 35.

- ↑ Greverus, Auf der Suche, p. 52.

- ↑ Greverus, Auf der Suche, p. 60.

- ↑ Ina-Maria Greverus, “L'identité et la notion de ‘Heimat’,” in: Ethnologie française, nouvelle serie, T. 27, No. 4, Allemagne. L’Interrogation (October–December 1997), pp. 479–90, here p. 481: “[S]i Heimat est certes un mot allemand, la notion qu’il recouvre n’est pas ‘un fait allemand total’, qu’elle ne constitue pas une composante immuable d'une ‘identité allemande’, mais un problème général lié à la territorialisation humaine et à la recherche de l’identité […].”

- ↑ Greverus, Der territoriale Mensch, p. 54.

- ↑ Greverus, Der territoriale Mensch, pp. 27ff.

- ↑ Celia Applegate, A Nation of Provincials: The German Idea of Heimat, Berkeley 1990; Alon Confino, The Nation as a Local Metaphor: Württemberg, Imperial Germany, and National Memory, 1871-1918, Chapel Hill/London 1997.

- ↑ A finding that has been confirmed by various scholars, e.g., Petri, “Deutsche Heimat,” esp. pp. 95ff.

- ↑ Applegate, A Nation of Provincials, p. 8.

- ↑ Alon Confino, “The Nation as a Local Metaphor: Heimat, National Memory and the German Empire, 1871–1918,” in: History & Memory 5 (1993), pp. 42–86, here p. 62.

- ↑ Alon Confino, “The Nation,” p. 8.

- ↑ Willi Oberkrome, „Deutsche Heimat“. Nationale Konzeption und regionale Praxis von Naturschutz, Landschaftsgestaltung und Kulturpolitik in Westfalen-Lippe und Thüringen (1900-1960), Paderborn 2004, pp. 41–5.

- ↑ Ferdinand Avenarius, “Heimatschutz,” in: Der Kunstwart 17 (1903), pp. 653–7, here p. 656.

- ↑ Avenarius, “Heimatschutz, ” p. 656.

- ↑ Willi Oberkrome, „Deutsche Heimat“, p. 513.

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte. vol. 3: Von der „Deutschen Doppelrevolution“ bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkriegs 1849-1914, Munich 1995, pp. 1068f.

- ↑ Oberkrome, „Deutsche Heimat“, S. 61.

- ↑ Eduard Spranger, Der Bildungswert der Heimatkunde [1923], Stuttgart 31952, p. 14, emphasis in the original.

- ↑ Joachim Petsch, “Heimatkunst – Heimatschutz: Zur Geschichte der europäischen Heimatschutzbewegung bis 1945,” in: werk-archithese 66 (1979), no. 27/28, pp. 49–52.

- ↑ Thomas Schaarschmidt, “Heimat in der Diktatur. Regionalkultur und Heimat-Propaganda im Dritten Reich und in der SBZ/DDR,” in: Martin Sabrow (ed.), ZeitRäume. Potsdamer Alamanach des Zentrums für Zeithistorische Forschung 2006, Potsdam 2007, pp. 176–9. In more detail: Thomas Schaarschmidt, Regionalkultur und Diktatur: Sächsische Heimatbewegung und Heimat-Propaganda im Dritten Reich und in der SBZ/DDR, Cologne 2004, pp. 38–236.

- ↑ Applegate, A Nation of Provincials, pp. 197ff.

- ↑ Confino, “The Nation as a Local Metaphor,” pp. 65-60; Schaarschmidt, Regionalkultur und Diktatur, pp. 505f.

- ↑ Thomas Schaarschmidt, “Heimat in der Diktatur,” p. 179.

- ↑ Habbo Knoch, “Einleitung,” in: idem (ed.), Das Erbe der Provinz. Heimatkultur und Geschichtspolitik nach 1945, Göttingen 2001, pp. 11ff. Knoch points out, however, that this has barely been investigated to date.

- ↑ Frank Bösch, “Die politische Integration der Flüchtlinge und Vertriebenen und ihre Einbindung in die CDU,” in: Rainer Schulze (ed.), Zwischen Heimat und Zuhause. Deutsche Flüchtlinge und Vertriebene in (West-) Deutschland 1945-2000, Osnabrück 2001, pp. 107–25. See also the brief bibliography in Adolf M. Birke, Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Verfassung, Parlament und Parteien 1945-1998, Munich ²2010, pp. 21f. and p. 100.

- ↑ See the overviews of literature in Rudolf Morsey, Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Entstehung und Entwicklung bis 1969, Munich, 5th ed. 2007, pp. 208–12; Andreas Rödder, Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1969-1990, Munich 2004, pp. 193f.

- ↑ The first were founded right after the war, though some were obstructed by the Allies. Later groups included the Pommersche Landsmannschaft (Pommeranians / 1948), Landsmannschaft der Oberschlesier (Upper Silesians / 1950), Landsmannschaft der Banater Schwaben (Banat Swabians / 1950), Deutsch-Baltische Landsmannschaft (Baltic Germans / 1950), Sudetendeutsche Landsmannschaft (Sudeten Germans). Local groups had formed beforehand which later joined the federal associations. See Andreas Kossert, Kalte Heimat. Die Geschichte der Deutschen Vertriebenen nach 1945, Munich, 4th ed. 2008, pp. 139ff.

- ↑ Kossert, Kalte Heimat.

- ↑ For the example of Bavaria, see Marita Krauss, “Die Integration von Flüchtlingen und Vertriebenen in Bayern in vergleichender Perspektive,” in: idem (ed.), Integrationen. Vertriebene in den deutschen Ländern nach 1945, Göttingen 2008, pp. 70–92, here p. 71, as well as more generally idem., “Das ‚Wir‘ und das ‚Ihr‘. Ausgrenzung, Abgrenzung, Identitätsstiftung bei Einheimischen und Flüchtlingen nach 1945,” in: Dierk Hoffmann/Marita Krauss/Michael Schwartz (eds.), Vertriebene in Deutschland. Bilanz der Integration von Flüchtlingen und Vertriebenen im deutsch-deutschen und interdisziplinären Vergleich (Sondernummer Schriftenreihe der Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte), Munich 2000, pp. 9–25.

- ↑ Annette Treibel, Migration in modernen Gesellschaften. Soziale Folgen von Einwanderung, Gastarbeit und Flucht, Weinheim, 5th ed. 2011.

- ↑ Knoch, “Einleitung,” p. 10.

- ↑ “Homelands and foreign places” and bureaucratization were the topics of the 10th German Sociologists’ Conference which took place in Detmold in 1950. See “Verhandlungen des 10. Deutschen Soziologentages,” in: Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie 3 (1950/51), pp 143–78. See in particular the relevant contributions of Fedor Stepun and Helmut Schelsky as well as the discussion summary.

- ↑ Uta Gerhardt, “Bilanz der soziologischen Literatur zur Integration der Vertriebenen und Flüchtlinge nach 1945,” in: Hoffmann/Krauss/Schwartz (eds.), Vertriebene in Deutschland, pp. 41–63. Gerhardt focuses in particular on the 1950s and 1960s.

- ↑ Schaarschmidt, Regionalkultur, pp. 275ff.; Palmowski, Inventing.

- ↑ Greverus, Auf der Suche, pp. 12f. and pp. 24–6.

- ↑ Jan Palmowski, “Building an East German Nation: The Construction of a Socialist Heimat, 1945-1961,” in: Central European History 37 (2004), no. 3, pp. 365–99, here pp. 377ff.; idem, Inventing a Socialist Nation: Heimat and the Politics of Everyday Life in the GDR, 1945-90, Cambridge 2009 (German translation: Die Erfindung der sozialistischen Nation. Heimat und Politik im DDR-Alltag, Berlin 2016).

- ↑ Günther Lange, who dealt with the socialist concept of homeland in the early 1970s, developing it in a new direction, assumed that Heimat and Vaterland were not the same, though he thought it necessary to emphasize their overlap; cited in Greverus, Auf der Suche, pp. 12f.